The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

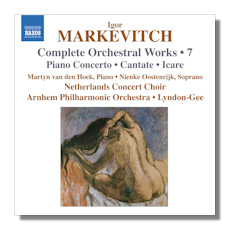

Igor Markevitch

Complete Orchestral Works

Volume 7

- Piano Concerto (1929)

- Cantate (1930)

- Icare (1943)

Martyn van den Hoek, piano

Nienke Oostenrijk, soprano

Men's Voices of the Netherlands Concert Choir

Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra/Christopher Lyndon-Gee

Naxos 8.572157 65:43

Also available on Marco Polo 8.225076: Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

Summary for the Busy Executive: A big noise, then silence.

Of all the "curious cases" in music, that of Igor Markevitch ranks as one of more strange. As a teen, he composed music that set Paris on its ear. Many considered him Stravinsky's chief rival, and Constant Lambert, an odd duck himself, called him the chief composer of the "Franco-Russian school." However, he stopped composing altogether in 1941, before he hit 30, and then turned to conducting. Not only did he cease to produce new original work, he actively discouraged anybody else from performing those pieces he had written. It took about a decade of persuasion before his death from the Director of New Music at Boosey & Hawkes, David Drew, to get him to publish or to republish his scores. Toward the end, he actually conducted at least one of his works.

This CD, the final volume in Naxos's seven-volume series of Markevitch's complete original orchestral scores (there's an arrangement for chamber ensemble of Bach's Musical Offering from 1949). As with most of the other series entries, the program consists of work from early to late. Of course, with such a short career, the standard categories of early, middle, and late run roughly four years apiece. Nevertheless, you can indeed make out three distinct periods. Here we have two early works and one curiosity, Icare (more on that later).

Diaghilev commissioned the Piano Concerto, one of his last commissions before he died. Markevitch was only 16, but he used his ears. The piece brims full of the sounds of the Hindemith Kammermusiken, of all things, not all that big in Paris at the time. Markevitch studied Hindemith with Nadia Boulanger, the Athena of so many 20th-century composers. The melodic shapes and baroque riffs of the first movement come from Hindemith's brand of neoclassicism, but one also senses here and there a personal sense of rhythm – one that disconcerts and subtly throws off or shifts the pulse by an eighth or a sixteenth. The three handsome movements – fast, slow, fast – function at Hindemith's level, with genuine expressive force. One considers this a student work only in the context of Markevitch's later development. Its assurance amazes me.

Diaghilev also commissioned a ballet from the boy, to be based on Anderson's "Emperor's New Clothes," with choreography by Serge Lifar, who had replaced Nijinsky in both Diaghilev's affections and company. Lifar, according to Lyndon-Gee's liner notes, had a higher-than-warranted opinion of his own talent. The long and the short of it: Diaghilev died and Lifar withdrew from the project, leaving Markevitch with a bunch of homeless music. Around this time, however, the composer met poet Jean Cocteau and the two decided to collaborate on a work. Markevitch thus salvaged his ballet music as the Cantate. He's now 17 or 18 years old. As good as the Piano Concerto is, the new work is even more solid. Hindemith remains the model, but Markevitch appropriates less directly. Frankly, I can't make head or tail of the Cocteau text, although the images startle. Reportedly, he wrote it under the influence of opium, and the text is more of a mood, rather than an argument. Markevitch sets the text against type. That is, the music moves clearly and purposefully – neo-baroquely – whereas the text has a surreal arbitrariness.

The work has four movements: fast, slow, fast, with a chorale ending. Exciting music fills the first three, with a wild and complicated fugue crowning the third movement. However, the chorale lifts everything to another level. Although it probably stems from Stravinsky and Hindemith in conception, the music itself, as its early audiences noted, found something new and visionary, a unique expressive place that came to fruition in Markevitch's ballet L'envol d'Icare (the flight of Icarus). The ballet astonished Markevitch's major contemporaries, including Milhaud, Bartók, and Stravinsky. I've talked about this work before (see my review), and I don't want to repeat myself too much here.

World War II led to a personal crisis. He split from his first wife, Kyra, Nijinsky's daughter, and fell seriously ill. He described himself during this time as "dead between two lives." His original work in Italy up to this point consists mainly of Lorenzo il Magnifico (reviewed here), in which we can feel a new warmth and lightness in his music. I believe this work profoundly influenced Markevitch's aesthetic, to the extent that he applied its viewpoint to L'envol d'Icare, now titled Icare.

The actual changes in the revision are few, and yet it feels like a completely different work. The number of measures remain the same. Markevitch changes most of the subsection titles. The Stravinsky references become less obvious, and yet the new ballet seems less individual. At the heart of it all lies the physical sound. Markevitch adds a bunch of countermelodies to the score, softening the acerbic qualities of the ensemble. L'envol also used a quasi-concertante group of instruments tuned a quarter-tone (the tone between a black and a white key on the piano) away from the rest of the orchestra. You might not think it, but it results in a profound distinction. The curious intensity produced by the clash of these solo instruments vanishes, leaving behind a good score, but not the visionary original.

To be fair, I'll mention that Markevitch preferred Icare and characterized L'envol as "unripe fruit." I think the original spooked him and the "correction" disappointed him, perhaps rendering him unable to continue along the lines of Lorenzo.

Pianist Martyn van den Hoek plays the bejeezus out of the piano concerto, especially the outer movements. Nienke Oostenrijk tames the very difficult vocal writing of the cantata. She actually sounds as though Markevitch's knots were the most natural turns in the world, and you can understand the words she sings. Christopher Lyndon-Gee and the Arnhem Philharmonic have, in this series, achieved stellar results. In this final volume, they give us the rough vigor of the concerto and the wild counterpoint of the cantata. They make a good case for Icare as a separate work. They may even have upset Markevitch's shaping of his career in that people have begun to think of the composer before the conductor.

I have reviewed the complete series. The additional reviews can be found through the links below:

- Volume 1 – Partita; Le Paradis perdu – Naxos 8.570773

- Volume 2 – Le nouvel àge; Sinfonietta in F; Cinéma-ouverture – Naxos 8.572152

- Volume 3 – Cantique d'amour; L'envol d'Icare; Concerto Grosso – Naxos 8.572153

- Volume 4 – Rébus; Hymnes – Naxos 8.572154

- Volume 5 – Lorenzo il Magnifico; Psaume – Naxos.572155

- Volume 6 – La taille de l'Homme – Naxos 8.572156

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.