The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

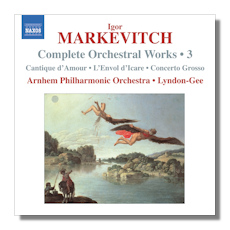

CD Review

Summary for the Busy Executive: Love and fear of flying.

Igor Markevitch broke into the front rank of European composers still in his teens and abandoned a flourishing career in favor of conducting before he hit 30. Not only did he stop composing, he discouraged their performance until very near the end of his life because he felt the works weren't "necessary." "Necessary" raises too many questions. Necessary to whom and in what way? Does enjoyable count? Some people don't enjoy Bach's music, after all, or Monteverdi's, for that matter. Necessary or important to the history of music or to other composers doesn't necessarily mean psychologically necessary to a listener. Why put one criterion at a lower level than another?

Unlike many composing conductors (Furtwängler comes to mind) and despite obvious influences like Milhaud, Honegger, and Stravinsky, Markevitch's music exerts great original force. Nadia Boulanger regretted his career switch to the end of her days. Hearing the works on this third volume of the seven in Naxos's edition of Markevitch's complete orchestra works, I agree with her.

Most of Markevitch's orchestral music exhibits the traits of leanness and acerbity. In a 13-year career a middle work (Markevitch stopped composing in 1941), Cantique d'amour, strikes me as a blip on the radar – his take on the Ravel of Daphnis et Chloé. He wrote it in the year he married Nijinsky's daughter, Kyra, in 1936, which might have had some influence. Because I've heard all Markevitch's music for orchestra, the lushness of this piece actually shocked me. An arch, it begins languidly, rises to a passion, and sinks back into torpor. The last section leaves Ravel behind for something closer both to Milhaud (akin to the opening of La création du monde) and to Markevitch himself.

In his liner notes, for some reason, Lyndon-Gee tries to de-emphasize Markevitch's debts to his French contemporaries and to the recent past. He claims that the Concerto Grosso owes far more to Hindemith than to Stravinsky or Milhaud. Markevitch's teacher at the time, Nadia Boulanger, put the teen on to Hindemith's Concerto for Orchestra of 1925, and they studied it intensively together. Markevitch then wrote his 1930 Concerto Grosso. The score does emphasize counterpoint, but not in a particularly Hindemithian way, and excepting only the first movement, certainly doesn't sound that much like Hindemith's score at all, or even like early Hindemith in general. Instead, the score takes an audio "snapshot" of Paris Modernism from the mid-Twenties on. The work, in three movements (fast-slow-fast), begins with a vigorous march, which to me owes as much to Honegger, Milhaud, and Stravinsky as to Hindemith. One catches a nod to Hindemith's melodic shapes as well as a little bit of Hindemith's concertante technique, but that general idea hardly confines itself to Hindemith among the Moderns. Yet overall one doesn't think of Hindemith. The rhythms, the nature of subsidiary contrapuntal lines, and the approach to the orchestra differ. Hindemith's sound doesn't get in your face, like Markevitch's does. They differ as a Brancusi differs from an Epstein. The Andante begins by referring to a Hindemithian long line, but it quickly becomes like many other Markevitch slow movements: an intense near-stasis evocative of ritual. The fast finale emphasizes bare-bones, two-voice counterpoint, but without Hindemithian affect. For one thing, the rhythms dance more jazzily than Hindemith (even in his jazz-influenced works). For another, in Hindemith, counterpoint stands almost as a symbol for cosmos, a number of voices joining together in a giant hymn to order. With Markevitch, it's more like several taxis turning onto the same street momentarily and then peeling off at random. We get two different visions of complexity and order, with Markevitch far more entranced by mundane chance.

The ballet L'envol d'Icare (the flight of Icarus) comes from Markevitch's twentieth year, and it belongs on the shelf of his masterpieces. Serge Lifar was to have choreographed it but, according to most accounts, chickened out when he saw the score. For me, it stands as one of Markevitch's most personal works, both musically and psychologically. The composer identified with the title character, especially after he gave up composition: the poet who meets failure by soaring as high as he can. Indeed, Markevitch believed this condition necessary to the artist. It's a seriously idiosyncratic re-reading of the myth. Daedalus, Icarus's father and the original myth's inventor of the wings, doesn't figure in Markevitch's telling at all. Icarus both creates the wings by studying the flight of birds and flies too close to the sun, thus doubly responsible for his own death.

The ballet contains remarkable music and unique sounds. The general idiom stems from Stravinsky, with at least one nod to Rite of Spring as well as to smaller pieces like Ragtime. Markevitch uses an orchestra with five instruments (flute, two violins, two cellos) deliberately tuned out a quarter step from the ensemble. Quarter-tones, promoted mainly by Czech composer and theorist Alois Hába) were big among the Twenties avant-garde. Even a relative conservative like Ernest Bloch used them. In my opinion, Markevitch made a most effective use. The emotion of the piece is intricately bound to the scordaturi. The music becomes harsher, more savage, even without a lot of volume. Occasionally, the music reduces to two instruments – one on standard pitch, one just slightly higher, and that pitch seems to linger in the air longer than a simple unison would. I can't praise the music highly enough overall. This really is as revolutionary a work as Le sacre. It hadn't the influence, first because in the Forties, Markevitch had effectively shut down his composition career and bad-mouthed his entire catalogue. He also revised L'envol d'Icare for the worse as Icare, turning it into something far more conventional. The man was apparently fiercely determined to bury himself as a composer and put a big old rock over the grave. Fortunately, he didn't succeed. This score is a powerhouse.

Lyndon-Gee and his merry Arnhem band play the bejabbers out of these pieces. One of the outstanding entries in Naxos's Markevitch set.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.