The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Summary for the Busy Executive: Crisis and struggle.

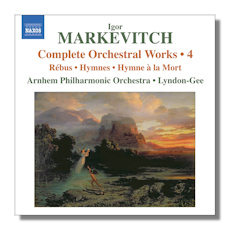

The conductor Igor Markevitch did not begin as such, but as a composing prodigy during the late Twenties. He made such a huge splash in Paris – the center of Modernism between the wars – that journalists referred to him as Prince Igor, Stravinsky being King Igor. During the Second World War, however, at the age of 29 and a thirteen-year career behind him, he gave up writing music. He also did all he could to make the world forget about what he wrote and damn near succeeded. That's the part that gets to me. I can easily imagine that he lost contact with the muse, but not that this would cause him to belittle what he had achieved. Fortunately, a few years before he died, he relented and gave his blessing to performances of his works again. Christopher Lyndon-Gee has led the revival, and Naxos has issued Markevitch's complete orchestral scores in seven volumes.

Rébus appears toward the end of Markevitch's early period. Of course, his career lasted so briefly that each "stage" runs only about four years. Still, I fancy that I can sense his creative arc, and I do think that he developed more quickly than most. For him, four years mark a bigger change than, say, for Haydn or Wagner. Rébus was a ballet proposed by Massine, but it came to naught. Massine had also proposed that Markevitch write a score to a dance movie the choreographer would direct. Markevitch wrote the first part of the score, the Cinéma-Ouverture, but apparently the financing fell through. In the case of the ballet, many feel that Markevitch's music scared Massine off. The ballet went unstaged in Markevitch's lifetime, but the music did receive concert performances.

A rebus is a puzzle consisting of pictures or symbols that represent words or syllables. In English, "IOU" is a very simple rebus (I owe you). There are such things as musical rebuses. For example, in the key of C, A - G - E - G - A, spells out "la - so - mi - so - la," ("lasso mi sola") or "let me alone" in Italian. Markevitch does not construct a musical rebus. Apparently, the idea was to hand out cards to the audience, perform the ballet, and have the audience guess the solution. I suspect that the rebus lay buried in the original movement titles: "Prélude au rébus," "Danse du pauvreté," "Gigue des nez," "Variations de pas," "Fugue des vices," and "Parade." The symbols "pauvreté," "nez," "pas," and "vices" yield the message "Pauvreté n'est pas vice" (poverty is no vice). What this has to do with the price of a malted escapes me, although it might make a veiled reference to the Depression. Incidentally, Markevitch incorporated large parts of the Cinéma-Ouverture (not played until more than a decade after Markevitch died) into Rébus. Most of the movements run together without a break. It begins weirdly, as self-absorbed as Stravinsky's Symphonies of Wind Instruments. This leads to a vigorous allegro, which has some of Hindemith's athletic propulsion as well as some of Stravinsky's nervy energy. A mountebank's gigue follows. The variations use a brief, very Hindemithian cell, used in a very Parisian way. Toward the end of the movement, the counterpoint becomes more and more complex, with jazzy syncopations so extreme, they become competing tempi. The counterpoint settles into a fugue, essentially a rewrite of the capping fugue of Markevitch's Concerto Grosso. There's more music and the instrumentation has been somewhat regularized. I prefer the terser, more pungent original. "Parade" caps off the ballet. It's a long span that grows increasingly louder, more raucous, and more rhythmically complicated. It re-presents themes from earlier movements, including the previous fugal subject. However, here it becomes a mocking and satiric march. The movement ends on a vulgar trombone slide into a totally unrelated key. Talk about musical surrealism!

The Hymnes seem mainly experimental – Markevitch trying things out. They weren't conceived as a group and appeared over several years. The last one written began as a work for voice and piano. The music itself seems like a surmise. There are five movements: "Prélude," "Hymne du travail," "Hymne au printemps," "Hymne troisième," "Hymne à la mort." The Prélude is a solemn, even severe, procession – another example of Markevitch's fascination with the stasis of ritual. As Lyndon-Gee points out in his liner notes, some of the music from a Markevitch masterpiece, L'envol d'Icare, found its way into the first hymn, "du travail," although Markevitch buries the references deep in the texture. In its heavy ferocity, it reminds me of Honegger's steam engine, Pacific 231. The second hymn ("au printemps") reverts to the atmosphere of the first and, as Lyndon-Gee notes, shares certain ideas. However, it moves more rhapsodically, as if the steady tread of the procession has loosened up, becoming "wavier." Much of it consists of a single instrument or duets. A melody without harmony that makes musical sense is one of the hardest things a composer can do, although Bach made it look easy. However, Markevitch often goes without implying counterpoint. It then moves to what I'd call a Bachian contrapuntal romp, with a chorale tune weaving through. It reminds me a bit of the finale to Honegger's Symphony #2, written many years after. We get trademark Markevitch competing rhythms toward the end, more complicated than usual. Yet it all "works out" together. The finale, a "hymn to death," again reverts to Markevitch ritualism, differing from the Prélude mainly by its proceeding contrapuntally. We get a few Stravinskian ostinati (notably, the minor third from Oedipus Rex), but counterpoint remains Markevitch's focus. Toward the end, we get new textures, suggesting radiance. The music could accompany the angels on Jacob's ladder.

Lyndon-Gee and his crew play magnificently music bristling with considerable interpretive hurdles. They make this enigmatic music sound, if not exactly natural, at least approachable. One of the best volumes of this series.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.