The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Nikolai Medtner

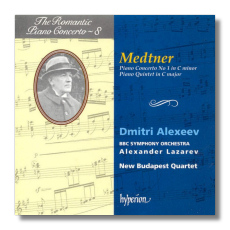

The Romantic Piano Concerto - Volume 8

- Concerto #1 in C minor, Op. 33

- Piano Quintet in C Major, Op. posth

Dmitri Alexeev, piano

New Budapest Quartet

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Alexander Lazarev

Hyperion CDA66744 58:59

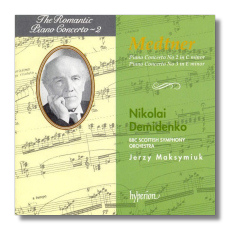

The Romantic Piano Concerto - Volume 2

- Concerto #2 in C minor, Op. 50

- Concerto #3 in E minor, Op. 60

Nikolai Demidenko, piano

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Jerzy Maksymiuk

Hyperion CDA66580 74:14

Summary for the Busy Executive: Love it.

Volumes 2 and 8 of Hyperion's "Romantic Piano Concerto" series stand out from the pack. I first came across Medtner's name forty years ago in an essay by John Culshaw on the Rachmaninoff and Medtner concerti. It's taken me that long to actually hear some Medtner music, undoubtedly my own fault. I had absolutely no use for the music of the Nineteenth Century, and its reach into the Twentieth struck me as a lingering illness, best stamped out. In the last twenty years, I've changed my mind somewhat. I can actually listen to Brahms and Beethoven with real enjoyment rather than narcosis. Of course, there were always grand exceptions, usually among the nationalists and especially among the Russians. I liked them because they didn't sound like Beethoven, Brahms, or Wagner. Their melodic and harmonic thoughts seemed to me far less predictable, as well as beautiful in their own right. Still, expanding my horizons meant exactly that: I didn't give up the old houses when I moved into the new neighborhood. For me, Russian music is still a fabulous luxury: rich, exciting, sensuous, something to wallow in. The emotions are epic (sometimes even over the top), and the music takes big strides. At its best, it risks a lot.

The point of Culshaw's essay was to show the similarities between Rachmaninoff and Medtner (1880-1951) and to make the case, at least for Rachmaninoff, as a great composer, since at the time Culshaw wrote, the composer's reputation (among most writers on music, at any rate) reached its nadir. Culshaw tried to describe the situation of a great composer during cultural decadence, by which he seemed to mean an artist who found something compelling to say with means generally considered played-out. I confess I have trouble following his point, probably because I don't accept the biological metaphor of birth, growth, and decay applied to aesthetics. Art isn't "natural" to me: that's what makes it art. Besides, it's more than a little paradoxical to say that the composer is great and the period stinks, since the composer makes the period. I suspect that some may take the sharp lines, drawn to define a period for pedagogical purposes, way too literally, as if once Debussy writes Prélude to the Afternoon of a Faun or Stravinsky The Rite of Spring, there's no such thing any more as Romantic music. Indeed, one could make the case that Romanticism is very much alive in contemporary art, that it has never passed on, in fact.

At any rate, my view conflicts with Medtner's own. He saw Modernism as a repudiation of Beethoven and the artists who followed. He considered himself a Beethoven disciple, although you may find it hard to hear this in the sound of Medtner's music. Medtner shares an idiom with Rachmaninoff. Both men knew and admired one another's work. Medtner may even have influenced Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto #4. But they don't write the same music. Rachmaninoff waxes far more lyrical, creating themes that flower into symphonic songs. Medtner works with Beethovenian "bits" that he strings together in long paragraphs. Rachmaninoff's works tend to carry the listener from one song to another. Medtner's force the listener to pay attention to a fairly close argument. The Rachmaninoff Third probably comes closest to Medtner's level of thematic development, but – unlike Medtner's music – it's not that sort of compositional concern that "makes" Rachmaninoff's concerto. While Rachmaninoff tried every genre, Medtner confined himself mainly to music for the piano. In both, however, one hears a lot of Russian "soul" – intense darkness, sweet singing, Orthodox Church modes and folk modes tingeing the harmonic sound. There is also an amazing level of finish to these works. Russian conservatory training (at least in Moscow and St. Petersburg) must have been among the greatest in the world. Medtner didn't write very much for orchestra. Indeed, I'm not sure whether there's anything other than the three piano concertos. Yet his orchestral writing shows complete command, if not necessarily an interest in novel sounds. One will not hear Stravinsky's aural inventiveness – rather, the Tchaikovskian template taken to a kind of limit.

Medtner's three concerti are all mature works, finished in 1918, 1927, and 1943, respectively. The first, in one movement, grows out of a rising semitone. To all intents and purposes, only two basic related ideas dominate the entire composition. Yet Medtner gives us an amazingly rich and various concerto, full not only of grand climaxes, but one which seems fairly taut. The originality of the structural thought also commends itself. One hears in large outline various classical forms, including sonata, but the thematic principle is that of Wagnerian continual variation. I can't easily call to mind any other work by anybody which actually pulls this off, for to a great extent these tendencies war with one another. The coda goes on a bit too long for me, but I can't decide whether the fault belongs to Medtner or to a momentary lapse of the conductor, Alexander Lazarev. After all, I've not heard any other recording.

If Rachmaninoff's third is his most Medtner-like, Medtner's second is the most like Rachmaninoff in its feeling, particularly the latter's epic second. It taps into the same primeval power. Medtner's concerto storms right from the opening measures and sings heroically throughout. The thematic unity, less concentrated than in the first concerto, nevertheless remains very tight, due to a recycling of themes from previous movements in the final one. It turns out that many of the themes relate to one another, particularly rhythmically. In this sense, it's also a very Beethoven-like concerto. The piece physically excites. The rhythms move the body.

Structurally, Medtner's third concerto follows the most unusual plan of the three, as one might expect from its subtitle "Ballade." Medtner connects two huge movements by an "Interludium" of roughly a minute-and-a-half, and he makes no reference that I can find to classical form. He explores the relation of three basic themes and also varies them with an abundance of invention. One of these variants becomes his most beautiful melody, very much like the lyrical moments of the Rachmaninoff second. Furthermore, when he comes across it, he knows what to do with it. He makes it a kind of emotional fulcrum of the work – the main point of contrast. Its final apotheosis, in conjunction with the opening theme, lifts the concerto to a grand conclusion beyond the level of formal culmination to a thematic argument. Furthermore, unlike so many works based on the principle of continual development and eschewing sonata form, the listener has very little difficulty making out the concerto's large rhetorical points. Medtner, as always, defines his argument clearly.

The Piano Quintet, Medtner's last major piece, for me dwells on a slightly lower plane than the concerti, although Medtner obviously intended this work as his spiritual testament. Words from the Psalms appear in the score over certain themes. Medtner refers to the shape of Russian Orthodox hymns and to the Dies irae chant. One can never fault Medtner's craft. And yet it seems less than the sum of its parts, or exactly the sum of its parts. Perhaps it's just not vulgar enough to suit me. The deadly air of gentility hangs over it. Also, the strings seem curiously de trop. The piano stars to the point where one wonders why this is a quintet at all. Don't misunderstand me. The piece contains moments of great beauty, particularly the entire second movement. I believe, however, that it fails to reach Medtner's usual even-higher level.

Lazarev and Alexeev do better than Maksymiuk and Demidenko, and Hyperion recorded them better. As should be clear by now, Medtner is a composer of subtle details and argument. Demidenko and Maksymiuk turn him into a barnstormer. They live for the moment, rather than to build in essence a musical cathedral. It gets so bad that both Demidenko and Maksymiuk fail to bring out the third concerto's principal major idea every time it appears. Furthermore, Demidenko is so closely miked that his piano drowns out the orchestral details, and the performance seems little more than a read-through. Nevertheless, I recommend both discs, simply because Medtner's works manage to triumph over even this level of thoughtlessness.

Other volumes in this series I've enjoyed include 5 (Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov), 6 (Dohnányi), 7 (Alkan and Henselt), 12 (Parry and Stanford – Parry rather than Stanford), 14 (Litolff), 15 (Hahn and Massenet), and 19 (Tovey and Mackenzie – Tovey rather than Mackenzie).

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz