The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

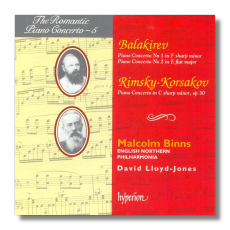

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov / Mili Balakirev

The Romantic Piano Concerto - Volume 5

- Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakoff:

- Piano Concerto in C Sharp minor, Op. 30

- Mili Balakirev:

- Piano Concerto #1 in F Sharp minor, Op. 1

- Piano Concerto #2 in E Flat Major, Op. posth

Malcolm Binns, piano

English Northern Philharmonia/David Lloyd-Jones

Hyperion CDA66640 60:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: Russian soul with sour cream.

Mili Balakirev has always struck me as a little son of a bitch - a bully, a virulent anti-Semite, a narcissist - just the person I wouldn't want to have dinner with. Fortunately, he and I will never meet. However, he must have oozed charisma, and he could be generous. In effect, he led three geniuses and far better composers - Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Borodin - to find their artistic selves, even if they eventually had to react against him. Furthermore, he composed marvelous music in his own right, although his output is small and punctuated by decades of silence.

Balakirev was an ideologue, a man with theories which he insisted upon. On the one hand, this focused him. On the other, some of these theories almost wrecked him. For Balakirev, "genuine" music had to express spontaneously the state of one's soul. Since souls apparently differed by nationality, a Russian composer had to express his Russian soul. He insisted on avoiding academic training. Of course a trained composer doesn't necessarily mean a great one and vice versa. On the other hand, training can allow a composer to concentrate on what's really important by letting him take for granted the 98% of composition that's dogwork and giving him facility in certain basic skills. The untrained composer you usually find in one of two camps: the composer who has to mentally argue with himself over almost every note; the composer who can do nothing but echo what he's already heard. The amateur composer's output is usually small and pastiche. Significantly, of Balakirev's colleagues in the Mighty Five, the composer with the most voluminous and varied catalogue is Rimsky-Korsakov, the one who felt the lack of training most keenly and (against Balakirev's advice - Balakirev was always free with his advice and sulked when people didn't take it) actually returned to study and "do his stodge."

Balakirev suffered from the ideas he held. He endured long periods of creative silence. Indeed, his second piano concerto, begun in 1861, he left unfinished at his death in 1910 (his friend Liapunov completed it). However, he did avoid, for the most part, the trap of pastiche. Almost all of his output shows a very original musical mind. His first piano concerto - really a first movement only, a Konzertstück - he composed in his teens. An impressive thirteen and a half minutes long, it points to a writer capable of real power, and, although it derives to a very great extent from Liszt and Schumann, many an older composer would have been justifiably proud to have produced it. The piano writing sounds full, idiomatic, and virtuosic. Its virtues are so many that its defects surprise one all the more - mainly, that it lacks a completely convincing narrative thrust. At least twice during the movement's course, Balakirev has to stop and start again. Here, the architectural reach of Liszt or Schumann, to say nothing of Brahms, eludes him.

Balakirev quickly left behind the obviously derivative idiom and indeed gave this as the reason for never supplying the other movements. He preferred to start again, with the result that he produced one of the finest concerti of the Romantic era. As far as I can tell, just about everyone who's heard this work wonders why pianists aren't lining up to play it. It's got just about everything: wonderful themes, splendid virtuosic writing, great orchestral color, moments to make you swoon or drop your jaw. The first movement has that bounding, soaring 3/4 quality of Beethoven's "Eroica." Like Balakirev's first piano concerto, this movement also lasts over thirteen minutes. Here, however, the composer doesn't run out of gas. It interests me, however, that Balakirev builds the movement just like academically-trained composers do. He elaborates and varies three thematic cells in what is essentially a slightly modified sonata movement. I have trouble imagining sonata form as a spontaneous expression of the Russian soul, so there's probably something in the notion of art as craft and, to some extent, as artifice. The second movement varies two themes. The first, based on the Russian requiem liturgical chant, seems rather unpromising for development: it begins and ends on the tonic (in c major or minor, for example, the tonic would be C; in D Major, D is the tonic note), the most stable pitch of the scale. Harmonically, it usually doesn't lead to anything new, and one would get music which merely repeated rather than developed. The listener wouldn't sense a journey through to somewhere. Balakirev solves the problem both simply and brilliantly. I won't spoil the surprise by giving it away here. The second movement leads without pause to the finale by way of a very brief passage based on the opening theme to the entire concerto. It differs from similar passages in Beethoven and Brahms in that it lacks structural weight. There's transition, but no sense of transformation from one thing to another. The effect is sort of like seeing a bird flit across the periphery of vision.

The finale startled me by its similarity to the corresponding movement in the Tchaikovsky B Flat Major concerto, down to the syncopations and thematic shapes, as well as a similar dazzle in the fingerwork. Tchaikovsky had little regard for Balakirev's music or his person, and Balakirev reciprocated the contempt. The similarities might arise from the fact that Balakirev never finished this movement, and Tchaikovsky came in through Liapunov. However, the bravura of Balakirev's piano writing was in the composer's toolkit from the get-go, and Balakirev left plenty of sketches and even played through an approximation of the movement for Liapunov more than once. Despite their mutual scorn, it may well be that Tchaikovsky and Balakirev had more in common musically than either realized. In the final moments of the concerto, the main theme of the opening movement returns, and though it receives an exciting treatment, again it falls short structurally. There's no preparation for it, and so it seems a bit mechanical, like the archetypal Bad Poet who insists on ending his poem with a repetition of the first line. As Charles Ives might say, it's like insisting that a man die in the same town he was born in. It's not quite that bad because the ending does make a good, though superficial, effect.

Those who have heard of the Rimsky-Korsakov concerto have undoubtedly noticed an underwhelming listener response. Those who have actually heard it have probably done so through Richter's recording with Kondrashin. Unfortunately, it bids fair to rank as the worst recording Richter ever made, mainly due to a truly horrid, obfuscatory recorded sound ("electronic stereo," yet!), so bad I couldn't begin to argue the merits or defects of the interpretation itself. Binns and Lloyd-Jones reveal a lovely, inspired work, as delicate and poetic as the Schumann concerto. Rimsky is less shaky structurally than Balakirev (the concerto develops one folk-like theme), but he's also less ambitious. Rimsky is there to sing, rather than storm the heavens. He sings beautifully, and his invention runs at a high level throughout. The work is in three short movements which proceed without break. The entire concerto lasts only slightly longer than the opening movement of either Balakirev. He's in, he charms you, he's out. The scoring bewitches, as you might expect. It isn't the Brahms d-minor, but damn, I do want to hear it again. I can't imagine the current crop of virtuosi spending the time to learn it, however, so this recording will probably have to do, which, it turns out, is as exquisite as the work itself.

Binns is quite fine throughout. Lloyd-Jones's English Northern Sinfonia does well in the Rimsky but seems a bit thick in both of the Balakirevs. In the Balakirev second, they tend to lose the sense of line in the first movement, stomping and tromping rather than soaring. However, overall these performers champion the composers and make a very strong case. Hyperion's sound is their usual quite fine.

As far as I'm concerned, this is one of the standout releases in Hyperion's Romantic Piano Concerto series. If you enjoy Russian nationalist music or are looking for new, worthy 19th-century repertoire, take a chance on this disc.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz