The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

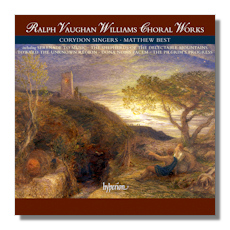

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Choral Works

- Serenade to Music 1,2,5-7,10-12,15,c

- Toward the Unknown Region a,b

- Psalm 47 "O clap your hands" a,b

- Psalm 90 "Lord, thou hast been our refuge" 11,a,b

- Fantasia on Christmas Carols 11,a,b

- Flos Campi 19,a,c

- The Pilgrim's Progress 16-18,a,d

- A song of thanksgiving 4,17,22,23,a,d,e

- Magnificat 6,21,23,a,d

- The shepherds of the delectable mountains 2,7,8,12-14,a,d

- The Hundredth Psalm 23,a,d

- Dona nobis pacem 3,11,a,b

- Agnus Dei

- Beat! beat! drums!

- Reconciliation - Word over all, beautiful as the sky

- Dirge for two veterans - The last sunbeam

- The Angel of Death has been abroad

- Four Hymns 7,20,a,b

- Lord! Come away!

- Who is this fair one?

- Come love, come Lord

- Evening Hymn "O gladsome light, O grace"

- Five Mystical Songs 11,a,b

- Easter - Rise heart; thy Lord is risen. Sing his praise without delays

- I got me flowers

- Love bade me welcome

- The Call - Come, my way, my truth, my life

- Antiphon "Let all the world in ev'ry corner sing"

- Three Choral Hymns 9,a,d

- Easter Hymn

- Christmas Hymn

- Whitsunday Hymn

1 Anne Dawson, Elizabeth Connell & Amanda Roocroft, sopranos

2 Linda Kitchen, soprano

3 Judith Howarth, soprano

4 Lynne Dawson, soprano

5 Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano

6 Catherine Wyn-Rogers, mezzo-soprano

7 John Mark Ainsley, tenor

8 Adrian Thompson, tenor

9 John Bowen, tenor

10 Martyn Hill & Maldwyn Davies, tenors

11 Thomas Allen, baritone

12 Alan Opie, baritone

13 Bryn Terfel, baritone

14 Jonathan Best, bass

15 Gwynne Howell & John Connell, basses

16 Aidan Oliver, treble

17 John Gielgud, speaker

18 Richard Pasco & Ursula Howells, speakers

19 Nobuko Imai, viola

20 Matthew Souter, viola

21 Duke Dobing, flute

22 John Scott, organ

23 Roger Judd, organ

a Corydon Singers

b Corydon Orchestra/Matthew Best

c English Chamber Orchestra/Matthew Best

d City of London Sinfonia/Matthew Best

e London Oratory Junior Choir

Hyperion CDS44321/4 4CDs 281:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Big box, with the advantages and limitations that implies.

This review may be shorter than the list of contents, but don't count on it. I dreaded going through this set. I bought all of these discs separately and found mixed results. I lost my favorite of the set, naturally, to Hurricane Katrina. I hate writing negative reviews, but Hyperion and Best have brands to uphold. I want to at least register a mild dissent from the chorus of praise these forces have received.

To be honest, I admit they have been highly lauded in places like CDReview and Musicweb. However, I sometimes couldn't tell whether the enthusiasm stemmed from the performances or from the works themselves, among the most beautiful in the Vaughan Williams catalogue. I have already spoken of the first disc of the set when it was released as a single (Hyperion CDA66420). So I won't take it up again here. Besides, the other CDs are considerably better then that one.

In 1944, after D-Day, it became clear that Germany would eventually lose the war. The BBC thus commissioned Vaughan Williams to write a victory ode while the fighting still went on. They even recorded it before war's end, but didn't broadcast it until Germany surrendered. Technically, this is an occasional work, but the composer manages to transcend the occasion, not by gloating, but by recognizing the cost of war and the humility that moral beings must take from victory. Significantly, it ends quietly rather than in a blare. The choice of texts is amazing. Vaughan Williams had to have been one of the most well-read Englishmen of his generation. In addition to lesser-known passages from Isaiah, we get parts of the Song of the Three Holy Children from the book of Daniel, Chronicles, Shakespeare's Henry V, and a setting of Kipling's "Land of our birth, we pledge to thee," one of the poet's non-jingo poems. The work calls for speaker, soprano solo, children's chorus, and chorus in addition to orchestra. The Kipling gets the "big tune," of the sort that VW almost always hit out of the park. Although it has a few rhythmic quirks, one suspects that the composer aimed for its easy adaptation as a hymn and its adoption into religious and patriotic occasions. It's not only a tune that almost anyone can sing, but that most would want to sing. The voice of speaker John Gielgud has worn to a husk, but it's still beautiful. He was worth every penny they paid him. Soprano Lynne Dawson electrifies in her opening. The children's choir, especially affecting in their part of the hymn, and the solid work of the adult choir also make this a noteworthy performance, a marked improvement over the original Forties recording. And it's stereo, yet.

The 3 Choral Hymns, written for the composer's own Leith Hill Festival in 1930, take essentially English translations by Bishop Coverdale of Lutheran hymns – "Christ is now risen again" ("Christus ist erstanden"), "Now blessed be thou, Christ Jesu" ("Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ"), "Come Holy Spirit, blessed Lord" ("Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott") – all, incidentally, also set by Vaughan Williams's musical hero, Bach. VW liked "Now blessed be thou" so much he joined two of its stanzas as one of the chorales in his Christmas oratorio Hodie. All three pieces are notable for refrains which VW turns into "garlands" of elaborate counterpoint, to paraphrase note-writer Christopher Palmer. I've heard two other performances which did this score no favors at all. Best allows the work's true stature to come through, although he should have made the counterpoint more clear.

The Magnificat (1932) shows the influence of Holst, particularly The Hymn of Jesus. It has its origins in an exchange between the British singers Steuart Wilson and Astra Desmond. Wilson jokingly suggested that it wasn't quite proper for young unmarried women to be singing magnificats. Astra Desmond said to VW, "I'm a married woman with four children. Why don't you write one for me?" Although VW was amused by Desmond's idiosyncratic theology, the idea stuck with him, and he did indeed write her a most unconventional Magnificat, in which he aimed to get "all the smugness" out. He couldn't have been thinking of Bach's, a piece he adored, but on the other hand he did produce something totally unlike Bach's exaltation. Instead of Bach's vigor and joy, we get sensuous mysticism, with the solo flute, characterized by the composer as "disembodied spirit," depicting the Holy Ghost. The composer, incidentally, frowned upon his setting's liturgical use. Palmer points out resemblances, especially in the writing for women's chorus, to Debussy's La damoiselle élue, which VW certainly knew. Best competes with Meredith Davies and Helen Watts on EMI (box set or single disc) and, I think, edges him out with Hyperion's superior sound.

Vaughan Williams first provided incidental music for a dramatization of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress in 1906. It proved perhaps his longest artistic involvement, lasting almost to the end of his life. In 1922, he produced the operatic scena, The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains, depicting Pilgrim's entry into the Celestial City. He began to consider a full opera and began to compose. However, it took him years. 1940 saw the little a cappella masterpiece Valiant-for-Truth, outside the opera proper, but surely in its gravitational pull. Worried he might not live to finish (hovering around 70), the composer incorporated chunks of the opera music into his Fifth Symphony. In 1942, he adapted some of it for a BBC radio production of the Bunyan book. In 1952, he completed his opera (he called it a "morality") The Pilgrim's Progress. This to me is its most realized form and ties almost the entire career of the composer together in music of incredible strength and consistency. The only reason I wouldn't call it his best work is because I'd have to choose from among too many candidates.

Nevertheless, Shepherds has claims of its own on a listener's interest. The composer incorporates large parts of it into the opera's final scenes, but there are significant differences. For one, it's more dramatically compact than the opera. It inhabits a more intimate space. VW makes his expressive points swiftly. He adapts of Bunyan's prose and his ingenious solution to incorporating Bunyan's Biblical marginalia surely and elegantly. The ending differs significantly from the similar point in the opera. Even with much the same music, Shepherds makes an altogether individual effect. Even by itself, it remains a major work in VW's catalogue.

Best turns in one of his finest readings of the series here. The cast is all first-rate, with Bryn Terfel as the Pilgrim standing out. For once, he actually sings excitingly without resorting to the hokey "opera-isms" that afflicted him later. His "Fain would I be where I shall die no more" thrills to the bone. Hyperion provides great sonics, and Best takes advantage of them to clarify the complexities of the different planes of action.

The Hundredth Psalm, also written for Leith Hill in 1930, is a mini-cantata. A minor work, VW later appropriated parts of it for the 1953 Coronation hymn. It's based on the well-known chorale tune attributed to Louis Bourgeois. It opens and closes with a joyful fanfare, but what happens in between never really takes flight. It's expertly written, of course, but that's faint praise, considering the composer we're dealing with. Best does nothing to change my mind.

A Bunyan Sequence is the music of the 1942 BBC Pilgrim's Progress production, essentially a radio play with music. Thus, most of Vaughan Williams's contributions fall under the heading of melodrama, music over which an actor declaims. I've never thought much of the genre. Either I want to hear the music rather than the speaker, or the music isn't necessary. That's somewhat the case here, although VW does better than most, treating the voice almost like a solo instrument and letting the music surround it, rather than cover it. Curiously, Vaughan Williams doesn't go to either the Shepherds or the Fifth Symphony for his themes. The next strike against it is that VW over-relies on paraphrases of the Tallis Fantasia. When this occurs in the opera, it occurs once at the emotional climax, to stunning effect. Here, you may just want to get out your favorite performance of the Fantasia and call it a day. However, there are also sections that show their operatic correspondences in embryo. The performance is quite fine, with Gielgud as Christian and Richard Pasco and Ursula Howells taking the other speaking parts – everybody turning in a splendid job. The choir has very little to do (why they bothered to include this piece in a "choral works" box, I have no idea), but Best and his orchestra do very fine work indeed. I suspect, however, that this disc is strictly for the composer's obsessional fans, like me.

In Best's Dona nobis pacem, we have one of the better performances of the set. Vaughan Williams pays homage to the Verdi Requiem in an anthology work which warns against war and which brings together one phrase from the Christian mass, a lot of Whitman, part of a parliamentary speech by Quaker John Bright, and passages from the Old Testament. It comes from the same period as the Fourth Symphony and shares much of the atmosphere. However, VW assembled it from old pieces in his desk drawer as well as sheets on which the ink was new. Yet one doesn't sense a stylistic jar. Instead, again and again the composer impresses you with the rightness of the music to the text – one of the greatest things he ever made. The choir is almost as good as Shaw's, at least in the matters of musical clarity and diction. Thomas Allen, with less of a voice, beats both Shaw's Nathan Gunn and Hickox's Bryn Terfel in just classy singing. His "Angel of Death" conveys the terror of text subtly. There's no hammy breathlessness, for example. It's the sound of somebody who wants to scream and can't. Still, Boult, Sheila Armstrong and John Carol Case take the fullest measure of the work, and, best of all, it's in the massive (30 discs) EMI VW box for little more than the cost of these four CDs.

On the other hand, Best's 4 Hymns for tenor, viola, and piano (or strings) (so also not a choral piece) really is the best version out there. The work appeared in 1914 as a kind of pendant to the better-known 5 Mystical Songs. The poets are Jeremy Taylor, Isaac Watts, Richard Crashaw, and Robert Bridges, and the poems "mystically" unite sensuality with the love of God. Best competes mainly with Ian Partridge and the Music Group of London (EMI box), the first I heard, and he blows them away. Normally, I count Partridge and the MGoL among my favorite musicians, but their performance convinced me that VW had misfired. Performers do make a difference. Tenor John Mark Ainsley sings passionately and with a beautiful line. Best and his Corydon Orchestra turn up the heat without losing the clarity or the subtlety of the counterpoint.

I believe Toward the Unknown Region of 1906 might be VW's earliest artistic success. Although it owes a huge debt to the choral music of his teacher Parry, it shows that VW had mastered the memorable, dramatic gesture almost from the beginning. He has, to an unusual degree, the ability to make you "see" music, as in the opening to the Symphony #1, "Behold the sea itself," where the curtain seems to rise on a limitless ocean. Here, he achieves it on the first two lines, "Darest thou now, O Soul, / Walk out with me toward the Unknown Region." A melodic lift to "walk" opens up the vista of the spiritual journey. Similar moments occur at "Then we burst forth" and at "O joy! O fruit of all!" Best does well, but falls behind Boult from the EMI big box. Boult just has the music in his bones.

O clap your hands is a small piece, perfect for ceremonies. It makes a joyful noise and would have suited the recent royal wedding down to the ground. Best and his forces are refined, but refinement doesn't count so much here. Willcocks and his trebles plus the English Chamber Orchestra give you the energy of the piece. Again, it's the EMI box.

With Lord, Thou has been our refuge, a meditation on the chorale tune "St. Anne," Vaughan Williams pays his respects to Bach. The piece comes from 1921 and for the most part follows the musical vein of his "Pastoral" Symphony from the same year. I've described the piece as follows:

Vaughan Williams juxtaposes the St. Anne chorale to Isaac Watts's hymn-paraphrase of the psalm, similar to several Bach cantata movements and organ preludes where a chorale tune steals in from left field against an apparently incompatible aria. The piece ends in contrapuntal fireworks (echoes and re-echoes of the tune at "Our shelter from the stormy blast"). Vaughan Williams busts the choir's chops. Most of the piece is a cappella, until at long last the orchestra (in this performance, the organ and the trumpet) finally joins in.

Only a top choir can even get through this piece. For example, vocal lines stretch out forever. If the singers lose pitch, they ruin the final orchestra entrance. Best makes a good decision to use Thomas Allen as a soloist, instead of a unison semi-choir. However, although Best and Corydon succeed technically, the emotion in the score in some part eludes them. For me, Paul Spicer and the Finzi Singers (Chandos CHAN9019) represent the gold standard.

Given the EMI big box, do you need this set? Certainly not for the popular pieces: Flos Campi, 5 Mystical Songs, Dona nobis pacem, Serenade to Music, Toward the Unknown Region, Fantasia on Christmas Carols. However, Hyperion also gives you either the only or the best recordings of little-known masterworks like the 4 Hymns, the 3 Choral Hymns, The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains, and A Song of Thanksgiving. Obviously, I've already made my decision.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz