The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

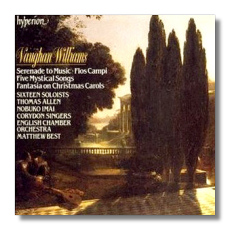

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Works for Chorus & Orchestra

- Serenade to Music *

- 5 Mystical Songs ^

- Fantasia on Christmas Carols ^

- Flos Campi **

* Sixteen soloists

^ Thomas Allen, baritone

** Nobuko Imai, viola

Corydon Singers

English Chamber Orchestra/Matthew Best

Hyperion CDA66420 68:17

Summary for the Busy Executive: Visionary music in earth-bound performances.

I can't tell you the last time I encountered a Vaughan Williams work on a concert program, as opposed to a church service. Even then, it was likely to be the hymn "Sine Nomine" or "Forest Green," rather than even something as simple as the anthem "Oh, how amiable." The number of new books on his life and work – that is, since his death in 1958 – I'd describe as "modest," at best. However, Vaughan Williams' music lives, and lives well, in recording, which means that a large band of listeners exists and programmers should take note.

Let's face it. Tastemakers suspect the accessible and often conflate it with the easy and unearned. They'd rather write about technical innovations in Britten's Curlew River than about the poetry and craft of his Ceremony of Carols. Vaughan Williams' "hard" music – in many instances, puzzling in its time – has lost much of its difficulty. The question remains whether it has therefore become crummy music. After all, we can ask the same of Beethoven. What continues to strike me about Vaughan Williams' hits are the risks he takes in each. Nevertheless, for me their beauty allows us to approach and even love them.

Oddness touches every item on the program here. In the Serenade to Music, the composer has written for sixteen solo voices and has given each a solo characteristic of that singer's style. Nevertheless, the piece doesn't fly off in sixteen different directions. The early Fantasia on Christmas Carols avoids well-known carols. Indeed, one of the them – "On Christmas Night" – achieved whatever popularity it has due to Vaughan Williams' arrangements of it. Other carols, like "The First Nowell" and "There is a fountain" (which I'm sure you all know) burrow in the orchestral texture but never receive a full statement. The work lives up to its title "Fantasia," in that one thing follows another, and yet, again, everything sounds of a piece. This should be mess of a work, but psychologically, at any rate, it all hangs together. The 5 Mystical Songs (the composer made two versions out of the same score: one with chorus, one without) sets the Metaphysical poet George Herbert, at the time the province mainly of 17th-century specialists and connoisseurs. Finally, one looks at Flos Campi pretty much the same way one looks at a platypus. What is it? you may well ask. A suite? A choral cantata with solo viola? A viola concerto with chorus? Add to this its polytonal, metrically free opening, its lush sound (from few forces), and its mood swings from barbarism to benediction, and you have at least a curiosity. Why have these works generated enough interest to have them recorded again and again?

I admit my view of Vaughan Williams runs counter to some very high-powered critics, but, when I consider some of their judgments, I have to conclude they haven't listened very hard. At any rate, I'd cite three reasons. First, Vaughan Williams is one of the greatest melodists who ever lived. The bon mot that his "best-sellers are not [his] own" – a joke VW appreciated – becomes insignificant in the light of all his great original tunes. Furthermore, he is simply one of the great setters of English poetry. Almost every poem he has set becomes his and no other composer's. His harmony is both unpredictable and inevitable. He doesn't merely come up with progressions nobody else thought of (although that's not nothing), but he takes the bones of Western harmony and puts them in surprising new contexts. I'd cite in particular the modulation in the Fantasia on Christmas Carols to "God bless the ruler of this house" – absolutely garden-variety, but in context miraculously fresh. Third, like Bartók, his counterpoint and sense of structure are both masterful and absolutely idiosyncratic. Add to this a unique and wide-ranging orchestral palette, something he gets very little credit for, and I think you get a great composer, as far as I understand great.

Furthermore, Vaughan Williams has two other skills that raises him above most. First, he can create the dramatic, memorable gesture and, what's more, could do so from his student days. In many cases, the music creates a near-physical response in the listener. In the opening to the "Sea Symphony," for example, at the words "Behold, the sea itself!" one "sees" a curtain raised to reveal the massive ocean. In the 5 Mystical Songs, the heart (or the mind) lifts at the words "Rise, heart!" Second, he makes what I can only call magic in score after score. I'd cite the opening descending chords in the Tallis Fantasia, the Serenade's transformation at "How many things by season season'd are," the opening to Flos Campi, even that modulation in the Christmas Fantasia, cited above. Again, most of these things are not his discoveries. The Tallis chords, for example, come straight out of Debussy and Ravel (with whom VW studied). But they don't sound like anybody really unleashed them before. Somehow, the context the composer has built, in this case solely through dynamic and orchestration, turns them into the music from under the hill. Many have written that this is nothing more than "manner," but if that were so, then it should be easy to imitate. Nobody else, even his most ardent disciples, sounds like Vaughan Williams or has that same wizardry.

The Serenade to Music, if you can believe it, began as an occasional piece. The composer wrote it in 1938 for the conductor Henry Wood's Jubilee. Wood wanted something that would allow him to honor sixteen singers who had worked with him. So part of the composer's challenge came with the commission. The music, however, turned out too good to abandon to the occasion, so Vaughan Williams, ever practical, made two other versions: one purely orchestral, the other for SATB choir with four soloists. The orchestral version has even been recorded, but I can't call it a success. It really needs the words. The SATB version gets performed, at least in amateur venues, and Sargent recorded it in, I believe, the Fifties. That LP introduced me to the piece. This version doesn't fail outright, but the original version (which I first heard from that non-eminent Vaughanian Leonard Bernstein) came as a revelation. The work transformed from secular cantata to mini-opera. It's by far my favorite setting of Shakespeare's words. Speaking of which, it's not even an obviously lyrical bit of Shakespeare, like "Under the Greenwood Tree" or something so well known as Roméo and Juliet's balcony bits, but large chunks of the Belmont scene from Merchant of Venice. Just the sound of its opening evokes perfectly a summer night, with a sense of the "vault of heaven" and breezes slipping through the orchestra. Indeed, it seems to me a perfect piece, not necessarily technically, but in the amount of psychological satisfaction it delivers.

How much you need this disc depends on what you already have. For my money, nothing beats the EMI series with Boult, Willcocks, and, latterly, Hickox. Matthew Best has the advantage of superb engineering (the sound of this CD is gorgeous) and a first-class chorus in the Corydon Singers. His soloists, with few exceptions, let him down. Since I haven't the score, I can't tell which soloist does what in the Serenade. My favorites were two of the sopranos. Thomas Allen disappoints me in the Herbert songs. His voice has acquired – as a conductor acquaintance of mine put it – "a beard," a rough edge that makes him sound as if he struggles through the middle register particularly. Also, little scoops mar his attacks. He sounds bogged down. I'm not a particular admirer of EMI's John Shirley-Quirk, but compared to Allen, he soars. Violist Nobuko Imai fights to find the interpretive groove in Flos Campi has plenty of company on that one. This score is notoriously difficult to bring off. Not only does the violist have much to shape (with little help from the composer, incidentally), but so does the conductor. Finding the right tempi (and the music speeds and slows like crazy) can drive musicians nuts. Aronowitz does well for Willcocks on EMI, but Hickox and Philip Dukes currently stand at the front of the line of all those I've heard. My major gap – ie, I haven't heard this – is Paul Silverthorne and Paul Daniel on Naxos. For the Christmas fantasia, I recommend either Barry Rose and John Barrow on EMI, Hickox and Stephen Varcoe (also on EMI), or Willcocks and Hervey Alan on London/Decca. It's a shame. The English Chamber Orchestra plays with great sensitivity, with superbly shaped solo lines. However, the star soloists weigh down what could have been extraordinary performances to the level of acceptable.

In all, I'd recommend the EMI boxed set of Vaughan Williams' major works (EMI 73924), all conducted by Boult. It runs around fifty bucks, American. You get the complete symphonies plus fugitive pieces like the Serenade in what remain benchmark performances. You can find better performances individually, but eight CDs at that price and at that quality strike me as a bargain.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz