The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Holst Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

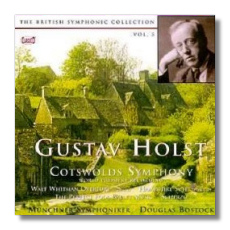

The British Symphonic Collection, Volume 5

Gustav Holst - Early and Late

- Symphony in F Major, Op. 8 "The Cotswolds" *

- Walt Whitman Overture, Op. 7 *

- A Hampshire Suite, Op. 28/2 *

- The Perfect Fool Ballet Music

- Scherzo for Orchestra

* World première recording

Munich Symphony Orchestra/Douglas Bostock

Classico CLASSCD284 65:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Missing the missing link.

Mature Holst mixes with juvenilia, including two world recording premières – the complete Cotswolds Symphony and the Walt Whitman Overture. Holst's creation over roughly twenty years of a personal idiom constituted no small part of his aesthetic achievement. He had come through composition study with Stanford possessing a solid technique, further refined by practical experience as a professional orchestral trombonist. But Holst suffered the trial of most artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the suspicion and the despair that everything had already been done. In England, the figures of Brahms and Wagner loomed very large indeed. Holst felt he had to, in his own words, "find himself" as a composer, and what's more he felt it as an almost moral imperative. It increased his already prodigious capacity for hard work. According to Imogen Holst's chronological thematic catalogue of her father's work, Holst wrote over 80 compositions – including the symphony here, an opera, several tone poems and cantatas, and a lot of big chamber works – before he hit on what we would now consider a fully characteristic piece: the Hymns from the Rig Veda, Op. 24. The Planets, Op. 32, is catalogue #125. One wants to know how he got from Stanford to himself. Unfortunately, this CD doesn't answer that question, and one experiences a severe disconnect between the Whitman overture and, for example, The Perfect Fool ballet music. We have here the beginnings and, with the Scherzo, the literal end, but not the journey or the momentous turn itself.

The Walt Whitman Overture (1899) comes across as almost pure Stanford, with occasional "touches" of orchestration taken from Wagner. Trying to find the seeds of the mature Holst, we detect a penchant for economy and for directness of thought as well as for "lean" orchestration. It's considerably thicker than the Real Holst, but svelte compared even to Stanford. It's almost Sullivanesque. It lacks, however, Holst's characteristic voice. There's less Holst in this than there is, for example, of Vaughan Williams in Toward the Unknown Region (1906).

The Symphony of 1899-1900, however, shows a real advance – a greater assurance in handling long forms and a greater determination to say something one truly wants to say, but only within movements. The movements taken as a whole are a hodge-podge of styles. The first movement, for example, delightfully vigorous and concise as hell, nevertheless sounds like the twee Olde Englishe music from the second rank of the middle-to-late Nineteenth Century. Every once in a while, one hears the Holst of the "Marching Song" (Two Songs Without Words) trying to peek out. Far and away the finest movement is the second, an Elegy ("In Memoriam William Morris"). This has been earlier and separately recorded, along with other Holst rarities, by David Atherton in Lyrita's magnificent Holst series (SRCD.209). Holst in his youth had more or less hovered on the fringes of British Socialism. To the Fabians, Morris was, of course, was one of the great social prophets and Whitman the great singer. Atherton's reading stresses the Wagnerian influences – the obvious inspiration of Siegfried's funeral march from Götterdämmerung and certain harmonic progressions. Bostock shows us Saturn about to come around the corner. Influence aside, Holst constructs an impressive arch of nearly ten minutes. The scherzo third movement lets us down with a thump. Most Modern composers found their way to Modernism in scherzo movements, where they felt permitted to indulge themselves in "the grotesque," just as most eighteenth-century poets found their way from Classicism to Romanticism through the genre of the ode. All that is missing here. With the exception of the lean scoring, Holst is firmly stuck in the past. You may well ask whether he needs to be FutureBoy. The Morris elegy shows that he doesn't, but the scherzo's material and the thematic treatment is far less distinguished, even at time clichéd. The beautifully-orchestrated finale, in striding triple-time, shows Holst reaching back through Stanford to Brahms, with a marvelous Big Tune in the second subject group of the same family as the main theme of the Brahms First. The development isn't up to Brahms, however, and in any case that kind of textural and motific complication was always foreign to Holst. Nevertheless, the movement coheres and says what it needs to without resorting to rhetorical inflation.

I don't consider A Hampshire Suite a genuine work by Holst. Gordon Jacob orchestrated Holst's second suite for band for orchestra. I have no idea why. Unlike Jacob's similarly disappointing arrangement of Vaughan Williams' English Folk-Song Suite, it hasn't caught on. I gripe about it mainly because, although pretty, it doesn't sound particularly like Holst, and Holst's original does. Jacob fails to imagine how Holst would have integrated the strings, and the string writing itself doesn't sound particularly Holstian – amazing, when you consider that Holst himself arranged the last movement for strings as part of his St. Paul's Suite.

By the time of the opera The Perfect Fool (1920-22), Holst could look back on his early Wagnerisms and, as the title suggests, kid himself about them. The ballet music has proved far more popular than the opera itself. I wonder how many people still alive have ever heard the complete opera. I certainly haven't. At any rate, the alert aficionado of the Ring will find little twists on major Leitmotivs and gestures in the ballet music, beginning with the opening trombone solo.

Holst wrote the Scherzo as part of a larger symphony. This was the only movement and the very last piece he completed before he died, relatively young, in 1934. Despite his considerable achievement, Holst felt as if he were really just getting started. There's the famous story of him listening to a radio broadcast of Schubert's cello quintet and realizing that what had been missing in his music was warmth. I think him way too hard on himself, but I do agree that the Scherzo represents a new vitality in his music, a willingness to tackle big things. I've always felt – in no small measure because of this work – that Holst's story was left unsatisfyingly unfinished. The music is part "Mercury," part "Mars," part "Spirits of Earth" (the Perfect Fool ballet), with a spontaneous power to it, as if it speeds into the listener's ear directly for the heart without a hitch. At the same time, it shows Holst's mature concision and the harmonic language of his late period – teetering on the edge of two keys, or standing with a foot on either side of the divide. Boult loved to perform the piece and recorded it on Lyrita SRCD.222. That symphony would have been a beaut, even alongside such monuments as the Vaughan Williams Fourth and the Walton First.

Bostock does what he can for the early stuff. It's much better than all right when Holst gives him something reasonable to work with. Indeed, I prefer his reading of the Morris elegy to Atherton's, for the reason I mentioned. It's also more spacious, closer I think to the inexorable tread of a true Holstian adagio. A Hampshire Suite never gets off the ground, in large part due to Jacob, but also to Bostock, who, by taking it a hair slower than he should, tromps through the first movement, and who fails to bounce in the last. The ballet music is okay, but you have many, many choices including Previn and Boult, both of them top-notch. Though Bostock and Boult run neck and neck in their timings of the Scherzo (Boult slightly faster), Boult leads with a greater sense of urgency and exposes the nerve more than a relatively relaxed Bostock, who lets the music breathe a bit. I prefer Boult, though I recognize that others may prefer Bostock's gentler approach.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz