The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Holst Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

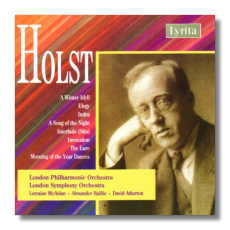

Gustav Holst

Orchestral Works

- A Winter Idyll (1897)

- Elegy (In Memoriam William Morris) from "The Cotswolds" Symphony in F Major, Op. 8 (1899-1900)

- Indra, Symphonic Poem Op. 13 (1903)

- A Song of the Night Op. 19 #1 (1905)

- Sita - Interlude from Act III Op. 23 1

- Invocation Op. 19 #2 (1911) 2

- The Lure, Ballet Music for Orchestra (1921) *

- Dances from The Morning of the Year Op. 45 #2 (1927) *

1 Lorraine McAslan, violin

2 Alexander Baillie, cello

London Philharmonic Orchestra/David Atherton

* London Symphony Orchestra/David Atherton

Lyrita SRCD209 76m ADD/DDD

One can hardly believe the funk among artists – writers, painters, and composers – at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th. Writers were vainly trying to escape Tolstoyan idealism, Flaubert realism, or Swinburnian decadence. Composers especially fell prey to the dispirit that – among Wagner, Brahms, Debussy, and Tchaikovsky – everything had been done and that there was nowhere new to go. Of course, one could stamp a work with one's individual personality, but the work would still resemble its real father – this, before one of the greatest explosions of artistic creativity and innovation in the history of the West.

Holst and his friend Vaughan Williams felt the search for what they termed the "authentic" within themselves very much as a moral imperative. Typical of their very practical natures, however, they didn't sit waiting for the muse to guide their pen. Instead, they wrote reams of music – often music that outstripped their technical skill, but nevertheless the best they were capable of at the time and submitted it to pitiless self-criticism. Those who regard Holst as bursting in from nowhere with The Planets of 1914 don't see the nearly twenty years of sheer hard work that preceded.

To some extent, one can't blame them. The composer's daughter, Imogen, kept the trunk pretty firmly shut, refusing nearly every request to push the early scores to performance. Her study of her father's work had come out when his critical reputation lay at a fairly low point, and she felt it served him best to emphasize the progressive aspects of his output – the quartal harmony, the bitonal counterpoint, the idiosyncratic neo-classicism. In addition, she selflessly devoted herself to editing performing versions and to producing and conducting high-quality recorded performances of the almost-forgotten works of Holst's mature and late periods. She did most of these for Argo, and the resulting LPs became classics of the stereo era and ignited new interest in the non-Planets Holst. Her father's stock rose among scholars of the period. At least one study from the early 1970s, for example, rates Holst over Vaughan Williams. Toward the end of her life, she began to relent and released works toward which she had felt unsure. It seemed less important to promote Holst the Progressive than to fill in the details.

Holst began under the influence of Wagner, despite his two most important teachers' (Parry and Stanford) allegiance to Brahms. His conscience wouldn't allow knowing, direct steals, and in any case Wagner's musical procedures struck him as a bit too lush. His early course was to combine Brahms' architecture with Wagner's color and atmosphere. A Winter Idyll, for example, written when Holst was still a student at the Royal College of Music, begins with echoes of the Flying Dutchman, down through its second theme and horn calls. The music broods in a Wagnerian way, sounding nothing like mature Holst, but nevertheless the student composer, not yet 25, impresses by the assurance with which he handles seven minutes' worth of large, late- Romantic orchestra. The "Elegy" movement for William Morris (Holst was a Morris Socialist, though not particularly active, in his youth) from the Cotswold Symphony brims over with Wagnerian reference – this time "Siegfried's Funeral March" from Götterdämmerung – and the Wagnerian- derived harmonic progressions become more pronounced. Still, the attitude toward scoring is more economical, without the subsidiary embroidery of the influence and with less instrumental doubling.

This is where Holst begins the road to finding his artistic personality. To some extent, early on he busies himself perfecting his orchestral and contrapuntal technique with ingenious self-challenges – a beautiful Ave Maria for 8-part women's choir among them, and probably the most successful of his solutions. However, he also feels the inadequacy of the idiom he inherited and begins to build a new one. Indeed, the idiom itself is arguably his greatest achievement, but it is quite idiosyncratic and unexportable, much like Van Gogh's painting style.

Of course, Holst's search for style is not strictly a musical matter. The style must suit what he wishes to express, and there's a lot in his head that he (characteristically) methodically must sort out. It's an odd tangle: the Sanskrit epics, English folk song and dance, Whitman, medieval poetry, the English Romantic school, rites of the early church, Arabic and Japanese music, and astrology. Furthermore, the journey to maturity is not an ever-forward march. Holst occasionally backslides.

As early as 1903, the symphonic poem Indra shows signs of the idiom of The Planets' "Jupiter." In contrast, A Song of the Night, written two years later, comes off as a nice, fairly conventional morceau. It's almost as if the subject matter gives Holst the permission to change the style. No inherited style suits the subject, so the composer must shape a new language. Fortunately, the language can express more than the Hindu epics, and we not only catch an early sighting of The Planets and Beni Mora but discover a lively piece in its own right. Lyrita always used good conductors and orchestras, but Atherton manages to get real passion from the London Philharmonic.

Holst's first big opera, Sita, barely gets a mention from daughter Imogen, and, based on the interlude recorded here, probably doesn't deserve it (the Wagnerisms come across like second-hand news), but it did occupy the composer for a number of years and that work paid off in his chamber opera Savitri, a remarkable, powerfully concise stage piece (Janet Baker in her prime gives a rapturous account on London 430 062- 2). Nevertheless, the end of the interlude grabs one's attention with some beautifully expressive wind writing that presage The Planets' "Venus."

The Invocation for cello and orchestra shows a considerable advance over A Song of the Night, both in inspiration and technique. The influence of folk song had been absorbed and had gone a long way to burning out the lingering Wagnerian spores. Still, the outstanding thing about the work remains its orchestration, often pitting single instruments against each other to great effect and with shimmering, clear combinations that tell us The Planets waits just around the corner. Again, Atherton and the cellist Alexander Baillie give an intense performance, as if the music really mattered, as opposed to Vernon Handley and Julian Lloyd Webber, who seem to indulge the composer with a "star turn" – a favor Holst needs less than he does committed advocacy. The work is no masterpiece, by a long shot, but it is genuinely lyrical, like Fauré's Élégie, and deserves a loving hearing now and then.

Much of Holst's catalogue – even the mature part – has problems in traditional venues. Much is short, choral, or intended for student performance. The operas are quixotic tilts at a public generally little interested in new music or drama (as opposed to blood-and-thunder melodrammer) or comic fantasy. The large works for chorus and orchestra inhabit a very personal imaginative realm. They're expensive to produce and, frankly, not everybody's cup of chocolate. The Lure is an 8-minute ballet to a very silly libretto about a moth attracted to a candle, which gets doused by a giant snuffer at the end. It's too short to attract a major company or to find its way to a concert program. At the time of its writing, British ballet, like British opera, represented an almost-perfect way to lose money, so it may not have seemed to Holst a good idea to produce a magnum opus, particularly since teaching seriously cut into his composing time almost through his entire career. After all, even a decade later, the most successful British ballet music, Vaughan Williams' Job, found its life not in the theater, but as a pendant to the symphonies. Nevertheless, The Lure buzzes with ideas, its energy recalling the ballet music from The Perfect Fool, written very near to it (1918-1922).

Holst described The Morning of the Year as a "choral ballet," which gives you some idea why you won't likely hear it live. Imogen Holst and Colin Matthews edited the score to excise the choral parts and left a continuous-movement suite of dances – a masterpiece, rhythmically dead- on and infectious with a generous supply of perfect tunes. Few composers have Holst's ear for the perfect placement of a note within a theme – the only ones I can think of right now are Grieg, Poulenc, and Stravinsky. In these dances, Holst recaptured the successful mix of inner rapture and popular appeal of The Planets. Atherton and, this time, the London Symphony give nothing less than stunning performances in both this and The Lure. The orchestral sound is both flexible and gorgeous, the rhythms go straight to the body, and each tune thrills.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz