The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Dvořák Reviews

Herbert Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

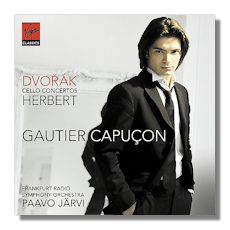

Gautier Capuçon Plays

Concertos for Cello & Orchestra

- Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

- Victor Herbert: Cello Concerto #2 in E minor, Op. 30

Gautier Capuçon, cello

Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra/Paavo Järvi

Virgin Classics 519035-2 DDD 61:04

It was only a matter of time before young (b. 1981) Gautier Capuçon recorded the world's most famous cello concerto … plus one by Victor Herbert. The coupling makes perfect sense, since it was Herbert's concerto that convinced him that he should tackle the genre himself when Dvořák heard it in the United States in 1894. ("The" Dvořák Cello Concerto actually was his second work in this genre, but the first, essayed some three decades earlier, was never completed, and seems to have left the composer unsure as to whether or not the cello was a suitable instrument for a concerto.)

Capuçon is nothing if not soulful in this work – one can imagine hordes of fans sighing over this CD. The second movement is most successful, because it is here that the cellist's romantic but not especially flashy playing is put to best use. The outer movements work well too, but they work best when the conductor and the cellist agree to swoon over the many lyrical moments … which Järvi almost exaggerates. So, if your view of this concerto is that it is heroic, and characterized by the composer's fierce love for his homeland, you might be disappointed by this recording. If, on the other hand, you are worried that, at times, the concerto hovers perilously close to bombast, Capuçon and Järvi might well please you with their suave and ultra-sensitive musicianship. Large or small (but more the latter than the latter!), Capuçon's tone is full of sweetness and song.

In the Herbert, of course we have a French cellist and an Estonian conductor with a German orchestra playing a work by an American composer who nevertheless was born in Ireland! Herbert's concerto, which predates his operettas, is relatively conventional, but it is idiomatically written for the instrument – among his other skills, Herbert himself was a cellist – impeccably put-together, and blessed with strong thematic material (although perhaps not enough of it!). Virgin's commentator (French, I believe) writes that "the work had only limited success, owing to [its] lack of stylistic unity," but I find that a little harsh. Its cyclical construction ties a neat bow around it.

As in the Dvořák, Capuçon and Järvi play the music subjectively, particularly relishing its quieter and slower pages, in which flexible tempos are the order of the day. Of course there are fewer recordings of this concerto than of the Dvořák, and the present one holds its own, not just because of the cellist and the conductor, but also because of the orchestra, which plays with plenty of attention to the music's shadings. Yo-Yo Ma with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic give listeners many "wow" moments in this coupling. Capuçon and Järvi offer more sighs than chills, and that's fine too. The engineering is very good. The Dvořák was recorded "during and after" live performances in Frankfurt.

Copyright © 2009, Raymond Tuttle