The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Busoni Reviews

Elgar Reviews

Prokofieff Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

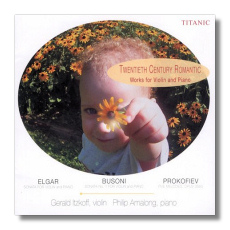

Twentieth Century Romantic Works for Violin & Piano

- Edward Elgar: Violin Sonata, Op. 82

- Ferruccio Busoni: Violin Sonata in E minor, Op. 29

- Serge Prokofieff: 5 Melodies for Violin & Piano, Op. 35bis

Gerald Itzkoff, violin

Philip Amalong, piano

Titanic Ti-265 67:38

Summary for the Busy Executive: Singing in the dark.

Someone has a bit misleadingly titled this CD "Twentieth Century Romantic." The Prokofieff may be lyrical, but hardly Romantic. The Elgar, like Mahler's music, inhabits a fluid space between Romantic and Modern. The Busoni, an early work, probably earns the Romantic label, the only work on the program to do so. So much for minor complaints against what undoubtedly constitutes a marketing attempt. After all, the word "Romantic" makes many people all warm and fuzzy, despite the many hair-raising examples of Romanticism from Beethoven through Wagner. The program really consists of works – none less than extremely interesting, and at least two considerably more than that – which deserve more recognition and exposure.

The Elgar sonata appears fairly late in the composer's career – one of four mature chamber-music masterpieces, consisting of the Sonata, the String Quartet, the Piano Quintet, all written toward the end of World War I, and the earlier Concert Allegro for piano of 1901. Elgar delayed writing these works because he made his living from music, and full-blooded chamber-music then as now didn't really pay. As much as we hate to admit, money does influence art. Elgar wrote them out of mainly idealistic impulses and complained all the while of the Philistine public. After all, most of Elgar's chamber music consists of saleable salon miniatures, like "Adieu" or" Chanson de matin," morceaus of genius, but lacking the structural sophistication of the four works above. Of them, I've always preferred the quintet, but most Elgarians disagree with me. Nevertheless, the choice really comes down to individual taste, rather than to an issue of quality. Some people would rather eat étouffée than duck-and-sausage gumbo. Like most of Elgar's war music (the cello concerto particularly comes to mind), the sonata bristles with psychological complexity and quicksilver mood shifts and ranges in mood from turmoil to nostalgic regret. One often senses an uneasy undercurrent in Elgar's music. In the violin sonata, subliminal becomes overt. Elgar takes advantage of the post-Wagnerian loosening of classical development and comes up with something as much fantasia as development, juxtaposition of fragments as opposed to seamless transformations of material. The chief psychological tone comes across as broken, even scattered, particularly in the slow movement, which proceeds by half-starts and sobs. I love the roughness with which Itzkoff and Amalong attack the first movement. They avoid the trap of Suave Elgar, which, I'm convinced, led to the view of Elgar as a smug musical Colonel Blimp. Emotions in Elgar's major works seldom reduce to complacency. Indeed, the music indulges like mad in nervous introspection. The epigraph to his second symphony – Shelley's "Rarely, rarely comest thou, / Spirit of Delight" – sums up much of Elgar's music for me. It's almost bipolar music – strong antipodal juxtapositions and long slides from triumph to despair. Itzkoff and Amalong get the turmoil of the music, but they miss the range of it, the subtle gradations between the poles. They read the sonata well, but, for my taste, too broadly.

Busoni composed his first violin sonata early, in 1891 at roughly age 25. It sounds to me like the work of a diligent student and no more. It's focused in its argument but lacks the intellectual extravagance found in works like the Fantasia Contrappuntistica, the Piano Concerto, and the operas that makes Busoni so interesting. This sonata is a well-crafted bit of second-hand Romanticism. Beethoven and Brahms provide the principal voices – Beethoven for the Sturm und Drang aspects of the sonata and Brahms for the lyric bits. Itzkoff and Amalong do what they can with the sonata, but without transforming it into something it's not. Indeed, Itzkoff and Amalong give pretty much their all, an attention to detail and delicate color (particularly in the slow movement, where the writing sticks like barnacles to the violin's low register) that would have benefited the Elgar.

Prokofiev's 5 Melodies come from 1925 (and California) but sound much later than that, like a pendant to something like Roméo and Juliet. After all, the Teens had hosted Prokofieff's "iron and steel" barbarism. The Twenties saw some smoothing-out, but still the composer came out with the massive second and third symphonies. These little pieces must have gone somewhat unnoticed at the time, since the standard view of Prokofieff at one time was that the Soviets had "tamed" the radical. But we see now that a yearning lyricism and a rapprochement with folk material belonged to Prokofieff even before he returned to the Soviet Union. The first movement always reminds me of the opening phrase of Gershwin's "I've Got a Crush on You," in a melting, languid waltz rhythm. The second seems like a Russian Fauré, as the harmonies slip and slide among keys with tenderness and grace. None of these gems would disgrace a larger work. Prokofieff works at the top of his considerable game here, folding a big emotional payoff into a relatively small package. My favorite performance – the one I imprinted on – comes from David Oistrakh and Frida Bauer, who come up with an account of great intensity. No one approaches that, but Itzkoff and Amalong take a different, warmer approach which suits the score very well indeed.

Both Itzkoff and Amalong know their instruments. Itzkoff has a lovely, full tone. Amalong has mastered phrase and color. However, they don't yet seem a fully-functional chamber partnership, as if they looked at the music in fundamentally different ways. Itzkoff has bravura. Amalong seems more able to delineate structure and more willing to collaborate in chamber mode. They need to get to know one another. There's nothing terrible about any of these performances. Indeed, the Busoni shows what they can do right now when they ride the same waves. The Prokofieff strikes me as genuinely heart-felt. On the other hand, I think of collaborations like Janet Baker and Gerald Moore, Oistrakh and Richter, Stephen Varcoe and Penelope Thwaites – not surprising that two of the three are singers – and yearn for that kind of communication between the collaborators.

The sonic image aims at the natural, a little on the dry side.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz