The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hanson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

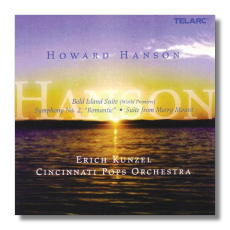

Howard Hanson

- Fanfare for the Signal Corps

- Suite from Merry Mount, Op. 31

- Bold Island Suite, Op. 46

- Symphony #2 "Romantic", Op. 30

Cincinnati Pops Orchestra/Erich Kunzel

Telarc CD-80649 DDD 66:12

Also released on Hybrid SACD:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

Summary for the Busy Executive: Radically conventional.

At one point, Howard Hanson owned a significant chunk of turf for American music. Head of the Eastman School for over forty years, he trained composers and performers and ran a large festival. Many of the composers featured in the Festival passed through Eastman in one capacity or another, but many had only the slightest of ties to the place. In addition, Hanson, a pretty good conductor, recorded for Mercury many, many modern American scores. I've read from one of his producers that he didn't always care for the music he recorded, but he did as he was asked and always turned in at least a conscientious, professional job.

Like Leonard Bernstein, Hanson made a persuasive advocate for his own music. Indeed, my introduction to Hanson's work took place largely through his recordings. Despite commissions to the end, after Koussevitzky's death, he never had much of a grip on the repertory of top American orchestras and practically none at all in Europe. When he died, I wondered how long his music would last.

American Modernists, particularly the students of Boulanger, Sessions, and Schoenberg, tended to dismiss Hanson's scores. Many of them kept their opinions among themselves, since they still wanted performances. Of all the prominent American composers in the first part of the Twentieth Century, Hanson deserved best the label Neo-Romantic. His music extended rather than overturned the late Nineteenth Century. He built his music with structural principles borrowed from Sibelius and César Franck. His music sounded as if Stravinsky and Bartók had never lived. One can at least understand the coolness of Modernists to Hanson's work, even while disagreeing with them.

His conservatism aside, Hanson never really copied anyone else. His music sounds nothing like Sibelius or Franck. Indeed, you can almost always tell a Hanson score after hearing a few measures. He had a genuine gift. His music, like Sibelius's for that matter, furthers Late Romanticism while innovating and invigorating it and poses intriguing "what-ifs" about the course of music in the Twentieth Century. The difference is that Sibelius had artistic progeny, while nobody as noteworthy came along after Hanson. His innovations, despite all his students, seemed to have died with him. As a result, Hanson seems not just individual, but isolated, in a way that other neo-Romantics like Barber, Bax, and Flagello do not.

Erich Kunzel, a wonderful musician, has taken up Hanson's cause with a nice mix of obscure pieces and Hanson hits. The Bold Island Suite receives its first recording, and the Fanfare for the Signal Corps (probably) its second.

In the Forties, the director of the Cincinnati Orchestra, composer and conductor Eugene Goossens, commissioned several American writers for fanfares in support of the war effort. These included Hanson, Harris, Cowell, Bernard Wagenaar, Piston, Gould, Deems Taylor, Virgil Thomson, Creston, and Goossens himself, among others. The series produced one enduring classic: Copland's Fanfare for the Common Man, which Copland later incorporated into his Third Symphony. As far as I'm concerned, however, most of these gems should be better known, Hanson's especially. Jorge Mester collected the series and some other Modern classical fanfares on a terrific CD titled Twenty Fanfares for the Common Man (Koch 3-7012-2-H1, not currently available). Hanson's Fanfare for the Signal Corps begins with a rhythmic canon for snare drums, perhaps symbolizing thousands of Morse-code message. The brass rush in headlong and reach an uplifting, satisfying conclusion in less than a minute. If the first audience didn't rise from their seats and cheer, they were probably coma victims.

The Merry Mount Suite comes from Hanson's only opera, Merry Mount, based loosely on the Hawthorne story. The opera had a big-deal première at the Met in 1930 and maybe one other Met performance a year later. There was so much ballyhoo surrounding the thing, that Dubose Heyward worried that it might eclipse the première of Porgy and Bess. He needn't have worried. After that, Merry Mount more or less sank. Some student productions or concert performances may have taken place in the Sixties at Eastman. At any rate, excerpts from the opera were released on a Mercury LP, lo, those many years ago. Hanson culled parts of the score into this suite, which (again released on Mercury) at least kept the music and the embers of interest alive. The suite became one of his best-known works, and deservedly so – full of great tunes. It alternates between lively dances and lush love music. Recently, Naxos published the entire opera, a CD which I plan to review in the next two years. I must say that the suite doesn't prepare you for the scope and power of the opera. Indeed, the suite strikes me as a kind of Pops-y piece, while the opera gives you Hanson at both his considerable best and his most ambitious.

The Cleveland Orchestra commissioned the Bold Island Suite in 1961. I don't recall it in any subsequent season. For me, it is a superb example of Hanson's late style. As he matured, he wrote more tightly, although he never lost his essential lyricism. Although not without melody, he constructs his themes less as complete units and more from smaller ideas, which he then plays with and recombines. Bold Island was Hanson's summer home in Maine. Superficially, the suite is a picture postcard of the island – birds, waves, sunlight, storms. However, it also shows some aspects of cyclical structure, with earlier themes showing up in later movements. There are three, all told: "Birds of the Sea," "Summer Seascape," "God in Nature." However, the work also reflects Hanson's theoretical concerns, particularly six-tone scales. Hanson even wrote a set of piano pieces (later orchestrated) called The Young Composer's Guide to the Six-Tone Scale. The first movement of Bold Island, for example, uses the scale C-D-Eb-F#-G-A – essentially, a major chord superimposed on an adjacent minor chord. "Realistic" bird calls enter, à la Beethoven's Sixth, and in time actually become woven into the fabric of the musical argument. "Summer Seascape" opens with an evocation of sunlight on gently lapping water. The clouds gradually darken and a musical storm comes up – nothing close to a hurricane, just a summer shower. The feel for the innate power of the Atlantic, even when relatively benign, comes through. Like Britten, Hanson seems to have the ocean in his bones. Not bad for a boy from Wahoo, Nebraska. The last movement, "God in Nature," strikes me as redundantly titled. The whole suite so far has celebrated an awe-inspiring power in nature. Here, however, Hanson makes things more explicit, using an original hymn-tune and a motive to the rhythm of "Gloria in excelsis Deo." The piece ends on a note of benediction, with the birds of the first movement having nearly the last word.

Also from 1930, Hanson's Second Symphony, subtitled "Romantic," probably counts as the most popular of his cycle of seven and likely due to the lyrical second theme of the first movement. I happen to prefer the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies, the last my favorite and also the least typical. Various writers have tried to turn the Second into a manifesto for the Eternal Values of Music, but, although a fine score, it's simply not strong enough as music to set an artistic agenda, as Stravinsky's Rite of Spring and Octet – or, in another direction, Sibelius's Fourth and Fifth Symphonies – did. Architecturally, the work is an odd duck. Again, Hanson uses cyclical principles throughout all three movements. In the first movement, we find two thematic groups. The first consists of subsidiary bits which combine and recombine in the development. The second comprises a complete song, which doesn't get developed at all. It is its own unit, complete in itself. The second movement, in song form, is my favorite of the symphony, with the most affecting passages. Bits of the first movement sneak in, mainly for tension and contrast, and transform the song into something more complicated. The third movement strikes me as the weakest, where a lot of the music seems to proceed on automatic and simply goes by. Even many of the recalls of earlier themes seem contrived. By the third-way point, Hanson comes up with a Sibelius-inspired set of paragraphs which lift the music out of its doldrums and builds to a climax over a very large span indeed. When the two principal themes from the first movement appear for the last time, it feels like a genuine summing up.

Kunzel does well in everything, but I simply can't get Hanson's own recordings out of my head – the spicy Eastman string sound, the beautiful solos from the Eastman wind players, and, above all, Hanson's conviction about his music. If you have the Merry Mount Suite, the Fanfare, and the Symphony already, no need to duplicate. If you're extremely lucky and have Charles Gerhardt's recording of the Second Symphony (to me, the best out there, but of course no longer available), you don't need Kunzel. However, Bold Island is definitely worth hearing and the sound will make you weep with pleasure.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz