The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Three Modern Choral Spectaculars

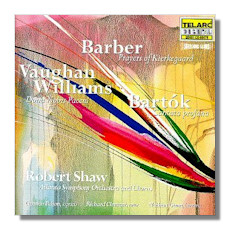

- Samuel Barber: Prayers of Kierkegaard 1

- Béla Bartók: Cantata profana 2

- Ralph Vaughan Williams: Dona nobis pacem 3

1,3 Carmen Pelton, soprano

2 Richard Clement, tenor

2,3 Nathan Gunn, baritone

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Robert Shaw

Telarc CD-80479 71:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Three overwhelming answers to three overwhelming questions.

It's almost overkill. Each work represents its composer at the top of his game. One might define a certain kind of genius as the ability to treat big subjects with breadth and depth. Vaughan Williams takes on "war, and the pity of war," Bartók the scary psychological darknesses of folk tales, and Barber the mystery of God Himself. As of this writing I have not been able to listen to more than one work at a time on this CD. Each one wrings you out.

I first heard the Barber not long after its première. Someone snuck me and some high-school choir buddies into a Shaw rehearsal of the Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus. Shaw has probably known this work since its beginning but never recorded it until now. He's collected at least thirty years' experience with it, so it's no wonder that this performance knocks over not only all the others on the CD but also the other recordings of the Prayers by Mester (on Albany) and Schenck (on Koch). The work has always reminded me of Holst's Hymn of Jesus – an evocation of what seems the history of western music. Both begin with modern Gregorian chants, and move to neo-Baroque counterpoint and twentieth-century rhythmic and harmonic frenzies. The difference between them is a paradox: Holst takes a passionate, mystical text and manages to keep his cool; Barber wraps intellectual mystical texts in music that packs an emotional wallop. At the same time, Barber writes more tightly than Holst. The opening chant seems to generate all the rest of the material. The language is a kind of chromatically-flavored modality (very suited to the opening chant) that Barber moved to in his late period. The liner notes point out the links to earlier works like Médea's Dance of Vengeance – I'd also add Knoxville: Summer of 1915. However, the music also points forward to the piano concerto and the opera Antony and Cleopatra. I have no idea why the Prayers aren't better known. They constitute one of the choral masterpieces of the century, and the language poses no difficulty to anyone who can listen to, say, Vaughan Williams without frustration. They must be hard as hell for a choir – particularly one drawn largely from a community amateur base – to learn, and they do need an orchestra. Shaw gives a searing reading. The difference between him conducting Atlanta and Yoel Levi conducting Atlanta on his Barber anthology CD is the difference between, in Mark Twain's phrase, lightning and the lightning-bug. Not that things couldn't be better, like diction. You do need to follow the texts in the liner notes. The opening chant is a bit stiff, as if the chorus learned it in a mechanical way. Shaw (and every other conductor so far) has problems with shaping the final chorale, rushing both the climax and the closing diminuendo. On the other hand, the double canon (at any rate, it sounds that way to scoreless me) in the second movement ravishes you, and the rip-roaring third prayer both rips and roars.

The Cantata profana, though adequately played and sung, suffers from the English translatorese of its original Hungarian text. In short, the main rhythm of spoken English is the iamb (short-long) while the trochee (long-short) is the main rhythm of Hungarian. The necessity of closing nearly every phrase with a feminine ending leads to a bunch of present participles long outstaying their welcome. Furthermore, the performance is too suave by half. This is the choral equivalent of Le Sacre du printemps. The syllables of the text should be hitting you like blows. Diction has to be razor-sharp. You're better off with Ferencsik on Hungaroton (HCD 12759) or Doráti on Hungaroton (HCD 31503). Furthermore, in the second part, choral intonation goes south – lots of singing around the pitch, a bit like Darlene Edwards. Indeed, it no longer sounds like a Shaw chorus. On second thought, strike "adequately."

Vaughan Williams' anti-war oratorio Dona nobis pacem I've written about in greater detail in my review of the Hickox CD. As far as I'm concerned, Boult (EMI CDM 7 69820 2) is the measure of all other performances. It ranges from white-hot rage and prayer to ecstasy and consolation. I find in it Vaughan Williams' learning from and re-fashioning of the Verdi Requiem into a tract for the times, warning against the rise of Fascism in the Thirties. By any emotional measure, it's a big work that takes big chances and succeeds in the risk. However, Shaw has the best choir by far. You can understand the words – essential in a work which aims to deliver a message. It consists largely both of poems by Whitman and of Biblical passages – in other words, poetry of some complexity, so the choir must work to achieve such clarity. The choir is rhythmically sharp and flexible. Intonation is spot on. Carmen Pelton, the soprano, is the equal of Boult's Sheila Armstrong. Although Shaw's baritone, Nathan Gunn, has a better voice (a more ringing tone) than Boult's John Carol Case, he sings worse, falling into what seems to be the contemporary trap of seldom or never hitting a note straight on, but with a Guy-Lombardo portamento. Still, the choir matters more, and Shaw undoubtedly has the better. The interpretation differs by quite a bit from Boult's, however. With Boult, you get a grand, majestic sweep, but at the price at times of textural mush. Shaw seems to strip away the heavy wax buildup from the work, trading some of Boult's grandeur for a bright, shining edge. Boult's reading tells us that Vaughan Williams' oratorio owes much to Elgar's; Shaw's emphasizes Vaughan Williams' quicker, more direct mode of expression. The Atlanta Symphony is just as clear as the chorus. I quibble with a couple of points in Shaw's reading – mainly, a choir-master hokey over-precision on certain isolated words in "The Dirge for Two Veterans" – but the final two sections (from "We looked for peace" to the end) have a coherence unmatched by any other account I know. Shaw has not only taken the trouble to analyze these parts thematically, he has drilled chorus and orchestra to always know which part in the heavily contrapuntal texture (the finale foreshadows the passacaglia of the Fifth Symphony) must be prominent. One hears the musical "spine" of the work. In all, one of the finest of Shaw's last performances.

Telarc sound is both lush and clear. How do they do that?

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz