The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bloch Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

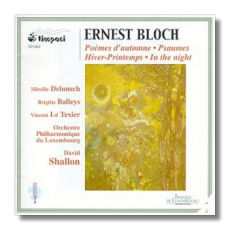

Ernest Bloch

Rarities

- Hiver-Printemps (1904-05)

- Poèmes d' Automne (1906) 1

- In the Night (1922)

- 2 Psalms (1912-14) 2

- Psalm 22 (1913-14) 3

1 Brigitte Balleys, mezzo-soprano

2 Mireille Delunsch, soprano

3 Vincent Le Texier, baritone

Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg/David Shallon

Timpani 1C1052 63:43

Summary for the Busy Executive: Finds.

In a way, I envy listeners who've heard nothing of Bloch but his Schelomo. Many happy surprises await them, including a magnificent series of string quartets and other chamber music, a terrific violin concerto, a choral tour de force, as well as other orchestral music. Bloch is, of course, as far as concert programming goes, pretty much a dead letter, but thank God once again for CDs. At one point in his career, many influential critics considered him a master. Ernest Bloch Societies sprung up mainly in Great Britain and in (of all places) Italy. The Second World War pretty much put paid to this adulation, both because of Bloch's removal from concert programs by anti-Semitic Fascists and by serious composers, temporarily swayed by Schoenberg and Webern.

Despite the dissonance level of his idiom, Bloch in essence was a Romantic, a Titanic composer of the tribe of Beethoven, Wagner, and Mahler – a glory and a limitation. In work after work, he reaches high. He never seems to play safe or to fall back on his previous successes. Sometimes, his reach exceeds his grasp. In America: An Epic Rhapsody, for example, he tells the history of the country through its folk and popular music, citing scores of tunes, all with the idea of showing the similarity of their "deep structure," which he presents as an original anthem in the final movement. As a feat of composition, it boggles the mind with its ambition and, in many places, with the realization of its ambition. But it also suffers from a cluelessness about the context of the tunes it uses, much like the German couple in Casablanca practicing their English with phrases like "What is it watch?" America is also the piece that pretty much banished Bloch from serious discussion of modern music. He would continue to write masterpieces, but very few talked about them.

One thinks of Bloch's music as having a distinctive voice, despite a fairly wide range of idiom – from neo-Romantic to neoclassical to dodecaphonic to something entirely individual. It cost the composer much work, and his development doesn't run a straight, ever forward-moving line. His techniques and styles demonstrate an omnivorous, eclectic musical appetite. In his maturity, his sources find new relationships with one another and a consistent artistic profile. His early music differs from his mature music in that it lacks that profile. For example, the set of tone poems Hiver-Printemps (winter-spring) show the strong influences of Richard Strauss, Mahler, and Debussy. Hiver seems the more individual, although its opening brings to mind Mahler's later Das Lied von der Erde. Mahler probably never heard Bloch, although Bloch certainly had heard Mahler. He traveled to Germany specifically to attend Mahler conducting his second symphony and was overwhelmed by it, going so far as to writing Mahler a letter about the deep impression it made. Nevertheless, large stretches go by in an idiosyncratic way, foreshadowing the contemplative Bloch of the Three Jewish Poems. The second movement hovers more conventionally between the Debussy of La Mer and Richard Strauss, the latter particularly at climaxes. It's all well done and bespeaks a large artistic nature, but its models surpass it and make it largely irrelevant.

Bloch's idiom emerges more strongly in the Poèmes d' Automne of the following year. Richard Strauss and Mahler largely get dumped, at least as far as musical cribs go, and Bloch gets to fight it out with Debussy alone. The poems that make up the four songs, by Béatrix Rodès, are pretty terrible. She was Bloch's mistress at the time (after a year, Mrs. Bloch put her foot down), and, boy! what love had done to him! – just as Mathilde Wesendonk had temporarily sent Wagner bonkers. Bloch actually makes something terrific of the second-hand, overripe verse (poetry lay beyond her), as Wagner had done with his inamorata's scribblings before. Over and over, we hear phrases that will show up in full glory almost a decade later in Schelomo. Common to both works is a meditative melancholy rising to great passion.

The psalm settings nudge up against that masterpiece, the earliest written two years and the last a year before. It shows. Debussy and Strauss are nowhere in sight. Bloch has hit on his first great synthesis of his style. These settings – actually, paraphrases in French by Edmond Fleg, the librettist to Bloch's opera, Macbeth – burn white-hot, masterpieces in their own right. From the opening orchestral prelude, the depth and intensity of Bloch's vision of the Old Testament roll over the listener. Psalm 114 conjures the vision of all nature awakened and bowing, practically vibrating with awe, before the Lord. Psalm 137 weeps by the waters of Babylon rising to a fierce promise never to forget the land of Israel and a fiercer curse on the Babylonian captors.

I believe one of the things geniuses do is raise the bar to a level inconceivable before they actually do it. The previous group of settings certainly fulfill all my requirements for great music, but apparently not Bloch's. The slightly later Psalm 22 takes the power of the triptych and adds to it not only greater structural, but also greater psychological complexity. A fanfare or two reminds the listener of Schelomo without in any way yielding anything to that work. If anything, it strikes me as even finer. I can barely get my mind around the fact that, in over forty years of assiduous Bloch collecting, this is the first time I've heard it.

Bloch wrote the brief In the Night in the Twenties, by which time he had fully come into his own as a composer. It exists in two other versions: one for piano solo (available on Connoisseur Society CD4208, programmed with Bloch's piano sonata, played by Myron Silberstein) and one, so say the liner notes, for violin and piano. Bloch orchestrated it in 1922, but its brief length (roughly five minutes) militates against live performance. Nevertheless, this nocturne packs a lot in a little space. An orchestral brooding gives way to the grand sensuality and lushness of the South Pacific, which haunts many of Bloch's works. Bloch was fascinated by Bali – that is, by the idea of Bali, since he never actually saw the place. The climaxes fall back into the opening brooding. This piece should probably come with a parents' warning label.

Shallon and his players fully commit to the music. There's no point in playing it as if it were Brahms. Its power lies in the rich, vibrant colors of the orchestra and in builds that hang on to the brink of over-the-top by their fingers. The worst piece on this disc is wonderful. A Major release of this neglected master.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz