The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- R. Strauss Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

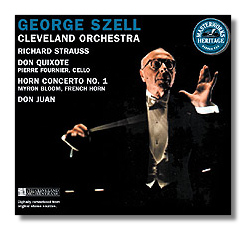

Richard Strauss

- Don Quixote, Op. 35

- Horn Concerto #1 in E Flat Major, Op. 11

- Don Juan, Op. 20

Pierre Fournier, cello

Myron Bloom, horn

Abraham Skernick, viola

Rafael Druian, violin

Cleveland Orchestra/George Szell

Sony MHK63123

Summary for the Busy Executive: The best stereo Quixote on CD. A must-have for Straussians.

Strauss's career spanned across centuries and, after juvenalia, divided into roughly three periods: orchestral, operatic, and orchestral again, with the second phase by far the longest. Of the first period, I find the tone poems Till Eulenspiegel's lustige Streiche and Don Quixote the most successful. Indeed, Quixote and the late Metamorphosen for 23 strings may constitute his most profound instrumental works. For some reason, Quixote doesn't seem to have received all that many recordings, compared to even a problematic work like Tod und Verklärung, and it almost never gets performed the way Strauss conceived it: as a kind of virtuoso piece for orchestra, with the first desks taking even more difficult leading roles. The cello part especially is so flashy that it has attracted just about every major star of the instrument. Feuermann recorded it at least twice, both times magnificently, even though the later performance (led by Ormandy) suffers from scrappy, muddy orchestral playing and mono sound. Still, Ormandy has to my mind also the most characterful Sancho Panza I've ever heard, violist Samuel Lifchey. Currently, you have your choice of Rostropovich, Ma, Feuermann, Tortelier, a host of lesser-knowns, and, here, Fournier.

Strangely enough, this performance has never before now been widely available. It appeared first on the old Epic label in roughly 1961, disappeared from the U.S. and resurfaced as a British CBS LP in 1969. During the early CD days, it showed up on CD and cassette, if at all, before vanishing from the U.S. market, probably coming to light in Japan and Europe. I loved both of my copies of the LP to death and waited like Patience on a monument for the CD's second coming. When Sony finally released it on their Masterwork Heritage series, I snatched it up. I say "strangely" because Szell's Strauss recordings have been almost universally praised, and with good reason. Strauss's idiom lay right up Szell's street. The conductor began as a composing prodigy using Strauss's language. He even became Strauss's conducting assistant in, I believe, Berlin. Szell never did less than superbly with Strauss's music, and several of his recordings have never been bettered. His Quixote belongs to the latter group. I should say that the handling of the introduction, Variation III ("Dialogues between knight and squire"), Variation V ("Vigil), and the finale – the meditative, as opposed to the descriptive sections – seem to make or break most performances for me.

Szell's opening phrase is a miracle of delicate fancy, transporting you into a fairy-tale world in two measures. The tiny fanfares lead to a curtain rising on the broad, sunlit Spanish plain – all, interestingly enough, without resorting to a specifically Spanish idiom. If nothing else, these measures adumbrate the master theater-composer Strauss later became. Details that normally don't come across in performance, like the opening extended oboe solo, flower under Szell. Strauss's scores gave Szell's technical side much to do. You will not likely hear Strauss's complex (and at times, overcomplex) counterpoint so clearly as with Szell. You can take for granted the smashing performance of the virtuosic orchestral sections (the sheep, the enchanted boat, the pilgrims, the windmill, and the flying horse). More importantly, Szell realizes their farcical genius and dream-like quality. The stirrings of the don's mania, represented by eccentric whirls, tics, capers, and buzzes in the orchestra, emerge unambiguously, simply because the players have absorbed the notes and because Szell has mastered rubato – here, an art that allows these quick little figures to sound at the most surprising moment, without dropping the larger rhythmic pulse. The "Dialogues between knight and squire" realize the depth of dramatic characterization far more completely than any other performance, as the music rises to the noble heights of the Quixote's apostrophe of the chivalric ideal. With "Vigil," that mood returns, bringing along a moment at the harp glissando that will just about rapture you out. This is some of the greatest night (and knight) music ever, comparable to Chopin or the Brahms choral nocturnes, where the music's "persona" seems to find its perfect, most profound place in the night's surround.

Of course, it's not all Szell. Fournier probably ranks as my all-time favorite cellist and may even embody my ideal string player. His phrases went on forever. I even saw him live on at least three occasions and, unless I looked, I could never hear when his bow changed direction. The tone was small, compared to someone like Maisky or Rostropovich, but warm. Furthermore, he seemed to have the interpretive mind of a super-grownup. One seldom exclaimed, "How passionate," but often reflected, "How deep." Fournier captures Quixote's nobility and foolishness (and indeed temper) with the fullness of a great comic actor. He and the orchestra meet in the interpretive empyrean. Comparatively, Skernick and Druian, first violist and concertmaster respectively, are simply in the car. Skernick, in particular, takes the spotlight only reluctantly, but Strauss gives even Sancho Panza good, though interpretively tricky, lines. They need a violist onto the deliberate clichés (depicting Sancho's flow of proverbs) and willing to rub our noses in them. However, few violists play this way.

From Variation X through to the end, Szell manages to rise from a great performance to something even more. The funeral march after the don's defeat becomes genuinely tragic, depicting not merely the death of an ideal, but of idealism itself. In Quixote's death scene, both Szell and Fournier, in perfect partnership, manage to make incarnate Cervantes' description: "The notary present remarked that in none of those books had he read of any knight-errant dying in his own bed so peacefully and in so Christian a manner." Still, Don Quixote remains primarily a fairy-tale, although one affected by a realistic portrayal of emotions very deep within us. When the opening tiny fanfares return at the close, they come as a glimpse of heaven.

Strauss's first horn concerto ranks as one of his most successful early works, far more assured than, say, the violin concerto, although it really belongs to his juvenalia, a period where he struggled to accommodate his notions of form to Schumann's, before he found his artistic salvation in his extensions of Liszt and Wagner. To quote Dylan, "It ain't me, babe." Still, the work has held the admiration of listeners and horn virtuosi alike. It's well-written for the instrument, the soloist gets to star in an heroic part, and its forthright exuberance wins an audience. For me, the great performance – legendary even among those of us who don't play the horn – is Dennis Brain on EMI CDC-7478342, with Wolfgang Sawallisch and the Philharmonia (coupled with the finest performance of the masterful and more emotionally and interpretively complex second horn concerto). Barry Tuckwell and Peter Damm (on London and EMI, respectively) do well, but their accompaniment lets them down. Myron Bloom, a great orchestral player, seems to lack virtuoso fire. His horn sounds less rich than Brain's or Tuckwell's, and he plays more modestly. Modesty is the last thing this concerto needs. Nevertheless, Szell and the Cleveland give Strauss their considerable best. You hear the shifts of orchestral texture and the byplay with the soloist, both of which revise the standard view of Strauss's early scoring for the better. Szell finds links not only to Mendelssohn and Schumann, but to Beethoven as well, particularly in the second movement. The rhythms just crackle and pOp.

Szell's Don Juan has never remained long out of the catalogue, if it ever left. It originally appeared with Tod und Verklärung and Till Eulenspiegel on one of the very greatest Strauss discs (CBS MYK36721), to my mind. Szell and the Cleveland surpass every other Don Juan performance I've heard. The almost too-familiar opening alone will raise you six inches off your chair. This Don Juan swaggers. The first extended love episodes blossoms fully, while the second rises to the height of the philosophic idealism of the Don himself. Nobody realizes this passage to Szell's extent. The accompaniment to the glorious oboe melody – often plodding in less capable hands – moves just enough to suspend time. The masked ball glitters. Szell takes the fiendish string runs at speeds faster than you would have thought possible, and the Cleveland responds without degenerating into mere slides. Overall, an elegant reading.

Engineers have performed marvels on the recorded sound of all three works. Columbia tended to overemphasize bass and restrict highs. For the Cleveland, this resulted in a dry orchestral sound, which surprised anybody who heard them live. Here, the orchestra sounds as warm as it did in concert, without crossing over to electronic Valhallas. An outstanding disc.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz