The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Herrmann Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

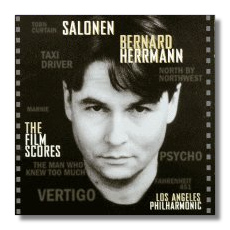

Bernard Herrmann

The Film Scores

- The Man Who Knew Too Much: Prélude

- Psycho: A Suite for Strings

- Marnie: Suite

- North By Northwest: Overture

- Vertigo: Suite

- Torn Curtain (Excerpts)

- Fahrenheit 451: Suite for Strings, Harps and Percussion

- Taxi Driver: A Night-Piece for Orchestra

Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra/Esa-Pekka Salonen

Sony 62700 DDD 76:45 Single-Layer Stereo SACD

Also released on CD 8279-69276-2

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

Summary for the Busy Executive: Herrmann at a distance.

If you asked film composers their five favorite predecessors, Bernard Herrmann would likely make all lists. While one can't claim Herrmann as the first to drag Hollywood film music into the modern era, he certainly rates as a pioneer, especially notable for bringing modern music into "general" pictures, out of the horror genre to which it had usually been confined. Herrmann approached incidental music "psychologically," rather than dramatically – that is, he concerned himself more with the inner states of his characters than on the story or on what the characters did. More than one film composer has pointed to a famous sequence in Psycho, when Janet Leigh is driving to flee the consequences of a theft, on her (unknowing) way to the Bates Motel (the cue known as "The Rainstorm"). Hitchcock shows you Leigh at the wheel and the view out the rear window – nothing more. Turn down the sound and you get a "flat" few minutes. Turn the sound back up and the guilt and inner turmoil of the impulsive thief become apparent – entirely through Herrmann's music. One could say that he showed us the monsters lurking not in the castle, but within us.

One can identify Herrmann's incidental music almost immediately, despite a virtuoso range of orchestral color (Berlioz, Ravel, Debussy, and Delius all influenced his approach to the orchestra) and of film type. He worked in just about every genre: film noir, "literary," science-fiction and fantasy, costume, adventure, romance, comedy, even western. However, most people identify him with Hitchcock thrillers and Harryhausen stop-action fantasies, despite the fact that he broke into movies with Welles's Citizen Kane and went on to work with Truffaut, Scorcese, and De Palma. Although an interesting, even quirky, melodist, he doesn't create particularly memorable tunes. You won't find a Max Steiner-ish "Tara's Theme" in his work. It's the gestures, the harmonies, and the colors that stick, as well as a certain efficiency. Some of Herrmann's most powerful moments come from the simple, repetitive alternation of two unrelated augmented triads. Furthermore, despite the typically thorny, aggressively modern nature of Herrmann's idiom, the music does indeed stick. For example, his theme for The Twilight Zone TV series became a running gag in the sitcom Roseanne.

The problems of playing Herrmann's music stem from the its leanness. The textures are so clear and so immediately apprehensible that the individual player has no place to hide. The movie music doesn't strike me as intricate, and I suspect that the crack Hollywood studio musicians produced usable takes fairly quickly, particularly when the composer conducted – almost all the time. Herrmann was used to time constraints. Before the movies, he'd been writing for CBS radio dramas, where deadlines press even more urgently than in film, and developed the ability to come up with and to place dramatically apt compositional haikus to enhance the play. The game seems to have been to write the least amount of music for the maximum effect. Here, Herrmann forged his epigrammatic style.

Practically all the music on the program repeats other CDs, almost always conducted by Herrmann himself. Check the London/British Decca catalogue. The Vertigo soundtrack, conducted by Muir Mathieson, appears on Mercury/Philips. The complete Psycho appears on Unicorn-Kanchana, led by the composer. Elmer Bernstein came out with a wonderful compilation on Milan. Bernstein also programs Christopher Palmer's stunning arrangement of Herrmann's music for Taxi Driver, titled the "Night Piece," and handles the jazz feeling of the score far more idiomatically (and raunchily) than Salonen. In general, I prefer complete soundtracks to snippets or "suites" thrown together. The question becomes why you should buy this CD, a potpourri of cues available other places. If you've been collecting Herrmann, you will recognize just about every track here. The answer comes down to how well you like Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Probably the most interesting music on the program to Herrmann fans will be the music never actually heard with the picture for which Herrmann intended it – Torn Curtain. The film marked the end of the Hitchcock-Herrmann collaboration. Hitchcock wanted a score which would yield a pop hit and Herrmann supplied what he thought the picture needed. Hitchcock halted the recording after he heard the bristling, in-your-face "Prélude" – a particularly brutal scene, by all accounts. Herrmann left Hollywood shortly thereafter for Britain. He would live to see his work vindicated by the new hot talent, who sought him out to work on their own movies. Elmer Bernstein recorded the complete score on LP, as far as I know never transferred to compact disc. The score is Herrmann's usual brilliant and would have helped a very weak picture. Incidentally, the soundtrack Hitchcock finally used not only didn't do much for the picture, it didn't even give him the pop hit.

The recorded sound is fine indeed. Herrmann's music suits Salonen's temperament: both composer and conductor tend to be drawn to emotional extremes. The program concentrates on the Hitchcock thrillers, plus Truffaut's Fahrenheit 451 and Scorcese's Taxi Driver. The L. A. Phil plays well, but not significantly better than the studio orchestras, the London Philharmonic, or Charles Gerhardt's National Philharmonic (a superb collection on RCA of lesser-known Herrmann film scores). Curiously, Salonen lacks the drama of Herrmann and others. He apparently wants to play it as music, rather than as incidental music – "not that there's anything wrong with that." Accordingly, he succeeds best in extended cuts and in a work like the Psycho "suite," which actually began life in a Herrmann Sinfonietta from the 1930s. He stresses the flow of the work above other conductors. One hears this most especially in the Marnie excerpts, Vertigo's "Scène d'Amour," and the Fahrenheit 451 suite. The ending of the last is one of the highlights of the CD, soaring and tender.

Yet, compared to Gerhardt and to Herrmann especially, Salonen doesn't seem emotionally or dramatically invested – unusual, because hitherto he's always struck me as a conductor who tended to go over the top. The Psycho excerpts, for example, are beautifully played, but I miss the usual bite and sting of the music. The overture to North by Northwest – a galvanic fandango – ranks as the most successful track on the disc, since it's the one cut where Herrmann's neurotic energy comes through. Unfortunately, it points up the deficiencies of the rest.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz