The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

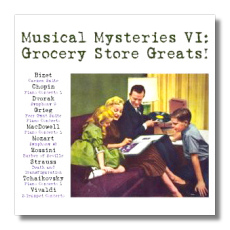

Musical Mysteries VI

Grocery Store Greats!

- Frédéric Chopin: Concerto for Piano #1 in E minor 1

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Concerto for Piano #1 in B Flat Major 1

- Wolfgang Mozart: Symphony #40 in G minor 2

- Edward MacDowell: Concerto for Piano #2 in D minor 3

- Edvard Grieg:

- Concerto for Piano in A minor 4

- Suite "Peer Gynt" #1 5

- Georges Bizet: Suite "Carmen" #1 5

- Antonín Dvořák: Symphony #9 in E minor "From the New World" 6

- Antonio Vivaldi: Concerto for 2 Trumpets & Orchestra in C Major 6

- Richard Strauss: Death and Transfiguration 7

- Gioachino Rossini: Overture "The Barber of Seville" 8

1 Noel Mewton-Wood, piano

3 Alexander Jenner, piano

4 Grant Johannesen, piano

1, 4,5 Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra/Walter Goehr

2,3 Vienna State Opera Orchestra/Henry Swoboda

6 Zürich Tonhalle Orchestra/Otto Ackermann

7 Utrecht Symphony Orchestra/Ignace Neumark

8 Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra/Alexander Kraanhals

ReDiscovery RD 110/111/112/113 ADD partly monaural 67:01, 64:06, 66:24, 59:35

Once upon a time, a little classical music was considered a good thing in American homes. Classical music LPs were status symbols: they demonstrated to your neighbors that you were educated and that you had good taste. In retrospect, this was, of course, absurd snobbery, but compared to today's dumbed-down expectations, it's almost worth getting nostalgic over. (Now, Americans often take more pride in what they don't know than in what they do know, and many parents instill a love for "good music" in their teenagers, I'll betcha, by picking up a Duran Duran or a Twisted Sister compilation CD at the mall. There, Johnny… that's real music.)

That's why I got an affectionate chuckle out of the photographs and texts reproduced in ReDiscovery's tray cards to this issue. The photos, dating from the 1950s, show a large gathering of well-dressed citizens from Syracuse and Rochester, New York. (To be sure, no one's pants are hanging halfway down their hindermost regions!) The occasion is the launch of The Basic Library of the World's Greatest Music, a series of 24 LPs of classical music issued by Funk and Wagnalls, sold cheaply at local grocery stores, with a new title available each week. Yes, Virginia, all these good citizens were assembled not just to eat cream of celery soup, but also to celebrate the fact that even the most middle-class housewife could bring Beethoven home, along with the potatoes and the canned tuna. "Speakers praised the Basic Library as ideal for inculcating knowledge and love of music," reads one caption. No less an expert speaker than esteemed music critic Dr. Sigmund Spaeth was present at the Rochester luncheon, and "he compared the records of the Basic Library with records ordinarily costing $4.00 or more." (Favorably, one assumes.)

If you're about 40 or older, you might have had some of those records housed in dark green boxes with the gold trim in your home when you were growing up. (We did.) Often, longer musical works were sneakily split across more than one record, thereby encouraging one to buy the following week's record, and so on. The boxes contained decent annotations about the music, but one looked in vainfor the names of the performers.

In time, we lost our innocence, and we were told that these records were junk. How could they be otherwise, given the fact that they were sold for giveaway prices in grocery stores, and that the performers were anonymous? Old sets or individual volumes of The Basic Library of the World's Great Music ended up molding in the basement, at library sales, or even in the dump. Now that a half-century has gone by, more or less, perhaps it's worth taking a new look… listen, I mean… at the Basic Library, particularly now that most, if not all, of the performers have been identified. Granted, you won't find Arturo Toscanini or Wilhelm Furtwängler on these discs, but you will find many interesting, spontaneous-sounding performances, as well as performers such as the pianist Noel Mewton-Wood, in whom there remains a small but intense knot of interest.

The hard-working and relentlessly curious folks at ReDiscovery have issued several CDs devoted to "musical mysteries": recordings in which the performers are either anonymous or pseudonymous. Whenever possible, they have revealed the true identities of the performers, and cleaned up the sound to a rather remarkable degree. The performances themselves often are well worth revisiting. This four-CD set is devoted entirely to recordings from the Basic Library -thus the phrase "Grocery Store Greats!"

Indeed, they are not bad at all, although one doesn't sense that hours and hours of studio time were scheduled for any of these give-'em-all-you-got performances. (For their occasional roughness, they are, however, gratifyingly "real" – not dishonest cut-and-paste jobs assembled by engineers post-recording.) I was very impressed with Mewton-Wood's Chopin and Tchaikovsky concertos, both responsibly accompanied by Walter Goehr and the Netherlands Philharmonic. Mewton-Wood fatally poisoned himself at age 31, apparently despondent over the death of his male lover, for which he blamed himself. Mewton-Wood's Chopin is particularly affectionate, yet it is not lacking in strength and brio. One consistently feels that he is taking a new look at the music and how it is to be shaped and phrased, and not merely submitting himself to received wisdom or tradition. Alexander Jenner's muscley MacDowell (with Henry Swoboda and the Vienna State Opera Orchestra) also brings something new to this underplayed but definitely meritorious concerto. (If it is not on the A List, it must be very high up on the B List.) Like Mewton-Wood, Jenner takes off the kid gloves, rolls up his sleeves, and turns in a very exciting and compelling reading. Johannesen's Grieg concerto (also with Goehr) is on a lower level. There are too many imprecisions in the dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra to be overlooked, and he seems to pursue easy effects instead of getting to the core of the work. Goehr's Peer Gynt music left me similarly underwhelmed, and his Carmen Suite is nice but hardlyr evelatory. Among the symphonic works, I was most impressed by Otto Ackermann's thrilling Dvořák, which is filled with loving orchestral detail and personality. (The Vivaldi concerto is Big Band Baroque, but no less enjoyable for that.) Ackermann's orchestra is theZürich Tonhalle Orchestra, and amazingly, even today that group retains some of the identity heard in this performance of the "New World Symphony." Another winner here is Strauss' Death and Transfiguration, with Ignace Neumarkand the Utrecht Symphony Orchestra. Neumark, a Pole who also conducted in Oslo and Palestine, is a forgotten conductor. Hearing this recording, one wonders if its evocative atmosphere and white-hot excitement were just a fluke, or typical of this conductor. If the latter, then are there other examples of this man's conducting out there? Swoboda's Mozart is big but not lumbering, and he accentuates the music's dark colors in an old-fashioned but still relevant performance.

Some of these performances have been on CD before. However, is as dramatically shown in a short bonus track, what you might have heard in the past bears little resemblance to what is offered here. Gideon's digital remasterings remove most of the glitches (not all are reparable) without adding echo or other unnecessary sweeteners. Most of his sources were the LPs themselves, but he also had access to tape in the case of Death and Transfiguration, which also is in stereo. Throughout, the sound, like the musicianship, is honest, and it should not get in the way of anyone's enjoyment of these unusual recordings.

As with other ReDiscovery issues, these are no-frills CD-Rs, although the little booklet contains good information and the photos mentioned above really send one down Memory Lane! The $35 price includes shipping and handling. ReDiscovery CDs can be purchased from their website: www.rediscovery.us

Copyright © 2006, Raymond Tuttle