The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Ginastera Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

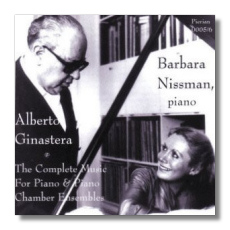

Alberto Ginastera

The Complete Music for Piano & Piano Chamber Ensembles

- Piano Sonata #1, Op. 22 (1952)

- Piano Sonata #2, Op. 53 (1981)

- Piano Sonata #3, Op. 55 (1982)

- Danzas Argentinas, Op. 2 (1937)

- Tres Piezas, Op. 6 (1940)

- Malambo, Op. 7 (1940)

- Doce Preludios Americanos, Op. 12 (1944)

- Suite de Danzas Criollas, Op. 15 (1946)

- Rondó sobre temas infantiles argentinos, Op. 19 (1947)

- Pampeana #1, Op. 16 (1947)

- Milonga from Dos Canciones, Op. 3 (1938)

- Tres Danzas from Estancia, Op. 8 (1941)

- Toccata by Zipoli (1970)

- Quintet for piano & string quartet, Op. 25 (1963)

- Pampeana #2, Op. 21 (1950)

- Sonata for cello & piano, Op. 49 (1979)

Barbara Nissman, piano

Ruben Gonzalez, violin

Aurora Natola-Ginastera, cello

Laurentian String Quartet

Pierian 05/6 74:10 + 72:34

Summary for the Busy Executive: Stunning.

Given the length of his career, Ginastera wrote very little, whether because he worked slowly or because he periodically dried up, I can't say. However, like Barber, much of what he did write musicians - often very good musicians - have taken up, and he even has classical hits with the classical-music public. The piano music, including the chamber music involving piano, comes from all periods. It divides into Big and Small. Obviously, the first two piano sonatas, the piano quintet, the cello sonata, and the 12 American Preludes fall into the first category. Ginastera arranged some of the rest from other works. Milonga comes from the late Thirties' 2 Songs, for voice and piano. The three dances from the ballet Estancia translate part of that work to the keyboard. However, "small" doesn't necessarily imply "trivial" or "light." Ginastera composed meticulously. I doubt he ever threw off a composition in his life.

I'll start with the big things first. The sonatas show mainly two, highly-contrasted moods: motor-like toccatas, derived I think from the rhythm of the South American dance, the malambo; very lyrical, pensive songs, the kind that one sings to oneself. The first piano sonata belongs to a time when Ginastera tried very hard to emulate Bartók's example, but with themes and rhythms based on Argentinean folk music. By me, it's one of the great piano works of the century, fully the equal of Bartók's own sonata of 1926. I know that if you examined a score, you'd find all sorts of fascinating relationships, since I can hear them in performance. The first movement, for example, varies two halves of an initial idea throughout its entire length. However, as with the Bartók sonata, a listener need not consciously take any of the architecture in. What comes across first is drive and passion, savage rhythms that get the body jumping. A troubled scherzo follows, with lots of cross-accents evocative of Latin-American dance and with a Debussian trio. The movement disappears in a puff of smoke. The slow movement starts by evoking the open strings of the guitar - an effect Ginastera exploited more than once, notably in the Variaciones concertantes and in the guitar sonata. A song rises to a passionate climax, diminishes the intensity to a tune with a guitar-like accompaniment, and ends with a pianistic plucking of guitar strings. The finale, markedly similar – primarily through the same rhythm – to that of the first piano concerto, stamps its way to a powerful conclusion. Overall, this sonata doesn't waste notes or time. Ginastera strives for concision, every idea a winner, aiming for maximum emotional effect.

The second sonata, one of the last things from the composer, takes the concision even further. For one thing, Ginastera eliminates the scherzo. Barbara Nissman claims that the work shows an harmonic advance, and the dissonance level has indeed probably risen. I have no idea whether Ginastera has in fact eliminated tonal centers, because it still sounds like Ginastera to me. The second movement, probably my favorite, is another "impression" of South American native music, evoking above all a wooden flute. It's very lonely music and reminds me, in a perverse way, of those large Chinese landscape paintings with a single human figure meditating in the midst of mountains, rivers, and waterfalls. The finale pounds its way practically without let-up to the conclusion. Ginastera avoids boredom by varying rhythms. Another really wonderful sonata and one which deserves the same sort of attention from pianists as the first.

The third sonata, the very last Ginastera composition - written during the composer's final illness - takes on the nature of meeting an obligation, since he wrote it to fulfill a promise to Nissman that he would write something for her. He originally thought of a concerto for piano and percussion (shades of Bartók yet again), but ten years later still had nothing written. He probably knew he was running out of time - hence, this one-movement sonata, another Ginasteran toccata. I find it meanders a bit. But again, it's still Ginastera, and he has done marvelous things. It bursts with that rhythmic dynamism he found early on and apparently never lost.

In his various suites and morceaux, Ginastera reveals himself as a superb miniaturist. Miniatures usually rely less on structural techniques and more on epigrammatic, immediately accessible ideas polished to maximum effect. You test a miniature by asking yourself whether it satisfies you and whether you'd want to hear it again. For me, Ginastera, who always passes both tests, reached the apex of this vein in his 12 American Preludes. The sonatas, undoubtedly great music, nevertheless mine a narrow expressive vein. Ginastera's miniatures attract, not least because of their variety of mood, melody, and rhythm. Here, the composer shows you his emotional and musical palette at its widest, if not its deepest. However, American Preludes add up to more than the sum of the individual items, most likely through their arrangement. This is not only twelve individual pieces, but a convincing artistic whole. Including the word "American" provokes the speculation that Ginastera wants to create a music that brings up two large continents, distinct from Europe. Some of the pieces are, as you would expect, dances, including again the malambo; some have the character of études; still others pay homage to those Modernist composers who have marked the path Ginastera wants to follow - Argentineans Juan Jose Castro and Roberto Garcia Morillo, the Brazilian Villa-Lôbos, and the U.S.'s Aaron Copland. The last pieces don't bring up any of those composers to me, but Nissman disagrees with me in the case of Copland. She connects Ginastera's prelude to Copland's early "Cat and Mouse." Certainly, the prelude conjures up that kind of picture (something chased by something bigger and more menacing), but yet again it sounds like Ginastera to me. The final prelude, however, calls to mind Debussy's sunken cathedral pretty strongly. What does that mean? I've stepped more deeply into my own mind, rather than Ginastera's if I try to answer that question, but I'll do it anyway. Just about every American artist is formed by two muses: his own vernacular idiom and the European tradition. The artist tries to pull off the trick of synthesizing these two strains into something characteristic, first of himself and second of his milieu. Arguably, we can view Ginastera himself as an exemplar of this and the preludes as one such creation.

The piano quintet comes from around the same time as the first piano concerto. It too concerns itself with the big statement and a serious outlook. It has much to admire. The composer lays out the work in four main movements - introduction, scherzo, slow movement, and finale - with three cadenzas interspersed. The cadenzas break down the quintet into low strings (cello and viola), high strings (the two violins), and piano. The textures are highly imaginative and individual. I can't easily recall a work that uses so many out-of-the-way string effects, other than the Bartók fifth quartet. However, I admire the quintet more than I love it. It belongs to those very few Ginastera works I think of as the "tenure-track file." It's just not vulgar enough to suit me. It strikes me as something written to gain respect rather than something the composer had to write. I miss the typical drive and heartbreaking lyricism.

No such problems with the cello sonata, however - a first movement full of fireworks and lots of double-stopping for the cello, a slow movement ardent and pensive by turns, and a crazed scherzo (at a subdued dynamic) which slams into an explosive finale. The composer wrote it for his wife, Aurora, a cellist beyond the common, and gave her a masterpiece. Again, some of the sounds Ginastera calls for from the solo instrument run a little to the weird, including moans, slides, and scoops; you could easily imagine them in an avant-garde piece whose only purpose was to annoy you. Ginastera, however, proves that music can come from even outlandish devices, if shaped by someone really musical.

The two Pampeanas (did Ginastera make up that word?) have long ago passed into the repertory of violinists and cellists. The first, for violin, opens with a recitative over the sounds of a guitar's open strings - one of Ginastera's iconic devices. For much of the time, the pianist doesn't play at all, and the violin, with very few notes, sings and accompanies itself. The passage has an almost classical chasteness. After the slow introduction, the violin and piano take up a dance of many cross-accents: often the old musical trick that six pulses to the measure break into either two groups of three or three groups of two. But it's fresh here - vital and springy. The end repeats the design so far - slow followed by fast - in more concentrated form. The second pampeana comes across as more rhapsodic than the first. The cello gets a greater opportunity to sing in its own time than does the violin. The work ends on still another roaring malambo.

This set restores to the catalogue two important recordings (originally on Newport Classics). Pierian does heroic rescue work with taste and imagination. All the performers are wonderful, but two stand out. Aurora Natola-Ginastera plays her sonata and pampeana as if it came from her blood. These aren't easy works, and many performers turn them into mere demonstrations of technique. She makes music. I have one quibble, but that's with the engineering, where the balance of the cello sonata's first movement allows the piano to dampen the cello often to mere buzzing. I doubt this accurately reflects Natola-Ginastera's playing, because she's wonderful in the other movements and in her pampeana. The major heroine of the set, however, has to be Barbara Nissman, a powerful pianist and a musician of laser-like focus. You know she has done all the head-work on the sonatas, but she comes over as a force of nature. She not only gets the steel and rhythm of the toccatas (and power without pounding), but above all she generates a wealth of color and an inexorable musical line, whether loud or soft. She hasn't had the career she deserved, mainly, I believe, because she got pigeonholed as a Modern "specialist" (her Prokofieff sonatas are tremendous as well). Nevertheless, I think she can play anything. I'd love to hear her Beethoven or her Chopin. If she played Brahms, I'd love to hear that. She has that combination of ardor and intellect. Strongly recommended.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz