The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- W.F. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

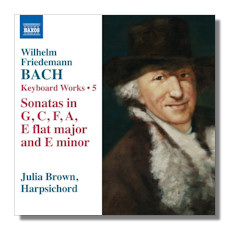

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Keyboard Sonatas, Volume 5

- Sonata in G Major, F 7

- Sonata in E Minor, F 204

- Sonata in C Major, F 200

- Sonata in F Major, F 6a

- Sonata in A Major, F 8

- Sonata in E Flat Major, Fk 201

Julia Brown, harpsichord

Naxos 8.573177

This year, 2014, is definitely C.P.E. Bach's year, of course. But Wilhelm Friedemann (1710-1784) has just as much to recommend him for lovers of the late Baroque and stil galant periods. Julia Brown, Director of Music and organist at the First United Methodist Church in Eugene, Oregon, and teacher, performer, and recorder of music has been quietly – but powerfully – assembling a series of recitals on Naxos of Friedemann's keyboard works. Volumes 1 and 2 (8.557966 & 8.570530) were released seven and six years ago (with Robert Hill in the former). Two years ago Classical Net was very positive about Volume 3 (8.572814). And equally so last year about Volume 4 (8.573027). Now here is the fifth in the series; and it's every bit as exciting, penetrating and enjoyable. Brown's performances are penetrating, sensitive and illuminating. It's not necessarily easy repertoire, requiring considerable technical strengths. And to have exciting and persuasive interpretations mapped onto unassuming virtuosity is a compelling combination.

In half a dozen sonatas Brown plays a modern harpsichord – by Richard Kingston, 1986 – to a tuning of a' = 415 (Kimberger). The pieces are three-movement, fast-slow-fast sonatas from various points in Friedemann's life. Their at times deceptive simplicity (the presto of the F major, F.6a [tr.12], for instance, with "competing" left and right hand themes) reflects the competence which the composer had acquired at the tutelage of his father.

Brown's playing does not (have to) pull us along with her through Friedemann's tergiversations and delayed recapitulations, tonal and harmonic experiment (as in the very next Sonata's (the A Major, F8 [tr.13]), allegro – almost chromatic in parts) and unexpected rhythmic summations. Rather, she lets the inventiveness of Friedemann work a subtle magic and almost play with our emotional response to the music.

It has been suggested that these are tensions born of the watershed at which music found itself in the second half of the Eighteenth Century. Brown's playing implicitly acknowledges, and explicitly works well within, that idiom. But it also uses a purity and untrammeled technique to expose and emphasize – to caress, almost (as in the aptly-named Largo con tenerezza [tr.14] of the same A Major Sonata) – the genuine inventiveness which one feels Bach would have embraced no matter what. She also shows in her playing how much the composer enjoyed and revelled in the "tools" at his disposal in even such a relatively small palette and compass: the keyboard as mightily expressive instrument.

There is great variety too in these pieces. Of tempo, texture, melodic invention, rhythmic originality (intrigue almost). Brown neither ignores nor exploits this color. She simply folds it into an exemplary technique to make for very compelling performances of very enthralling music. Neither Friedemann's nor her own virtuosity gets in the way of the great expressivity of the music.

If, as Brown suggests, Friedemann had too much music of his own creation to fit into a time when others were working in very different ways, her playing neither underlines this to attempt a spurious attempt at novelty, nor underplays its charm, its wit and its penetrating nature.

The acoustic is close and helpful, that of the AGR Performing Arts Center in Eugene, Oregon. The harpsichord fairly sparkles – yet to a mellow, genuine effect. The two pages of documentation that Brown has written make an excellent introduction to the music and its context. If you've been collecting this series, you'll not want to hesitate. If new to this lovely and substantial music, start here and work through the entire series: only a couple of those works presented here are already in the current catalog.

Copyright © 2014, Mark Sealey