The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Brian Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

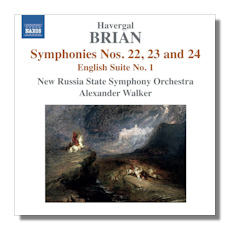

Havergal Brian

Symphonies

- Symphony #22 "Symphonia Brevis"

- Symphony #23

- Symphony #24

- English Suite #1, Op. 12

New Russia State Symphony Orchestra/Alexander Walker

Naxos 8.572833 65m

About two decades ago the music of Havergal Brian (1876-1972) was beginning to attain its first serious notice internationally with the issuance of a CD on Marco Polo of his massive Symphony #1, the Gothic. The recording, made in 1989, was issued in 1992 and reissued in 2004 on the label's parent company Naxos. I well remember reading about Brian in the 1990s, how he came late to the symphonic form, completing his first symphony at fifty-one, but managing to turn out thirty-one more before his death at ninety-six. He was especially active in his later years, composing twenty-seven symphonies after he was seventy-two. More than a few important conductors took up Brian's cause to one degree or another: Adrian Boult, Adrian Leaper, Charles Groves, Colin Wilson, Charles Mackerras, and Martyn Brabbins. Even Leopold Stokowski famously led the premiere of Brian's Symphony #28 in 1973 in a BBC broadcast performance. Yet, their efforts haven't quite made Brian a household name. But does he deserve greater fame and attention?

The three symphonies on this disc are all solidly crafted works that adventurous listeners may well find to their liking. I say "adventurous" not because the works are avant garde or truly tough listening, but because Brian wrote in a style where traditional symphonic forms were replaced by his own designs, and where the music, though almost always tonal, is often violent or seemingly inscrutable. Except in his early works, his music rarely seems to flow clearly and fluently from one section to the next, but instead conveys a sense of restlessness and eruptive power in what at first might strike one as a quirky parade of musical ideas. Brian favored march or march-like rhythms, as well as brassy scoring. Think of the more robust music in Vaughan Williams' symphonic works and the rowdier moments in Ives' scores and you will get an idea – but only an idea – of the style of the highly individual Havergal Brian.

Although Brian's First Symphony lasts nearly two hours, his later ones tended to be brief, in some cases very brief. The Symphony #22 here clocks in at 9:22, #23 at 13:44, and #24 at 16:29. They were written in a nine-month period in 1964-65 and form a trilogy, where march rhythms are a predominant factor. The two-movement #22 opens up in a state of conflict but soon settles into a temporarily subdued but restless mood. The music then becomes stately and seems to be struggling toward a triumphant resolution when it abruptly ends. The second movement, while a march, is both playful and menacing and features lots of percussion. After much struggle, several violent outbursts bring on momentary silence after which the music slowly fades away in F minor amid a few percussive rumbles.

Cast in two movements, the 23rd Symphony also begins in conflict and, with F minor hovering above the proceedings, seems in many ways a continuation of the previous symphony. There is a sense of the music changing almost constantly as it roils and develops, with percussion punctuating many chords. Finally peace comes near the end of the movement, but the succeeding Adagio starts off restlessly and quickly develops a seething manner. The middle section is relatively calm, even if the mood exudes a sense that dark forces are lurking around the corner. The music soon builds amid much tension from brass and percussion to reach an emphatically triumphant resolution.

#24 is a somewhat brighter work than its two siblings – not that it doesn't have its disruptive and rowdy moments. Cast in a single movement, it begins in an optimistic mood and is often quite playful. The brassy and percussive scoring here tend to add color, sometimes even a sense of exoticism, to the often festive mood of the music. Just when you think the music is turning dark midway through, a jovial bassoon reverses the mood swing and the remainder of the symphony is a mixture of the cheerful and the serenely confident. Some of the writing for strings in the latter half more than vaguely recalls Vaughan Williams.

The English Suite #1 (1905-06) is completely different in style and sound from the symphonies, not least because it was written over a half century before! We're practically back in the world of Tchaikovsky in this six-movement work, but there is an English regalness or folkishness in much of this utterly charming music. The opening panel, Characteristic March, is chipper and has echoes of both Elgar and Tchaikovsky. Valse alternates subdued and charmingly suave music with infectiously energetic music. #3, Under the Beech Tree, recalls Tchaikovsky again, and most pleasantly. This could almost serve as a dance from an English counterpart of The Nutcracker. Interlude takes us into a sort of fantasy world, with celesta and harp prominent in the scoring. Hymn is solemn and slow but conveys a lightness of mood in its brass scoring. #6, Carnival, is a colorful smorgasbord of tuneful music that even offers a festive version of My Country 'Tis of Thee. So why isn't this catchy early piece more popular? Beats me. It is brilliantly scored and utterly infectious in its melodies.

The performances here by the Alexander Walker-led New Russia State Symphony Orchestra are spirited and accurate, and the Naxos sound reproduction is vivid and quite powerful. In fact, you may want to cut back a bit on the volume as the music was recorded at a very high level. All in all, this is a fine release.

Copyright © 2013, Robert Cummings