The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

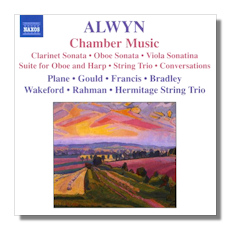

William Alwyn

Chamber Music

- Clarinet Sonata

- Oboe Sonata

- Viola Sonatina

- Suite for Oboe & Harp

- String Trio

- Conversations for Clarinet, Violin & Piano

Robert Plane, clarinet

Lucy Gould, violin

Sarah Francis, oboe

Sarah Jane Bradley, viola

Lucy Wakeford, harp

Sophia Rahman, piano

Hermitage String Trio

Naxos 8.572425 TT: 75:53

Summary for the Busy Executive: Four gems, two masterpieces in fine performances.

One of the many fine British composers overshadowed by the likes of Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, and Tippett, William Alwyn really made his mark from the Forties to the Fifties, after which his music more or less flew below the radar. Lyrita recordings kept his name alive, and recently his music has made a comeback on CD, particularly due to the excellent Naxos and Chandos series of his music. If you want to hear most of Alwyn's major (and even a lot of minor) scores, you can, with the exception of the opera Juan, or The Libertine.

The chamber music on this CD runs from early to late. The early music tries on a range of styles current in Britain at the time, but mostly hanging out in Waltonian neighborhoods. We have just begun to get Alwyn's very early music, although necessarily in bits and pieces, since he destroyed most of his scores before 1939. The Oboe Sonata, from 1934, sounds a bit like a cross between Hindemith and Vaughan Williams in its rhapsodically pastoral first movement, with a theme built in part from fourths, fifths, and sevenths, and with its largely modal color. The second movement, which opens with a miraculously lovely triple-time chorale in the piano, over which the oboe adds a further comment, at times sounds like one of Ravel's evocations of old dances. The finale lightens the mood with a jazzy waltz. Throughout this modest work, the level of invention remains very high. Fortunately, he didn't get his critical mitts on it.

The Viola Sonatina appeared in 1941. By this time, Alwyn's music had begun to assume the features of mature style – big, passionate, neo-Romantic. It begins with an impressively grave statement, which leads you to expect something grand. However, the movement lasts only two minutes. The second movement, "Dance: Allegretto," trips lightly and decorously. An "Aria: Andante piacevole" follows. "Piacevole" means "tenderly." As in the first movement, it leads you to expect something bigger. The last movement, with a vigorous main theme again breathing vaguely Hindemithian air, stamps and flies to a breathless finish. My only complaint with the sonatina is that I wish Alwyn had followed the implications of his first and third movements. A very substantial viola sonata might have emerged.

In 1945, Alwyn composed the Suite for Oboe and Harp for the virtuosos Léon Goossens, pre-eminent British oboist of his time, and his sister Sidonie. This deliberately small-scale work premiered on the BBC. The first movement, labeled "Minuet," is an exercise in orientalism, the second a pastel waltz. The finale, in its outer sections a jig with an occasional hitch, has a quasi-Irish ballad for a middle.

From 1950, Conversations for clarinet, violin, and piano is a suite of eight miniatures. Technically, its most interesting feature is that the instruments tend to play sequentially, rather than together, excepting, of course, the piano, which in addition to its moments in the spotlight also provides steady background accompaniment, so the effect is very much like a conversation among the instruments, each speaking more or less in turn. Alwyn writes elegantly, in the sense that he uses not a lot of notes to make his effects. My favorite movements consisted of a calm beauty of a chorale, an ingenious, lively fughetta, based on a theme of repeated octaves, an atmospheric "Carillon" depicting the listener nearing church bells from a distance and then leaving them behind, and an appropriately quirky triple-time "Capriccio" finale with a bluesy middle.

Now for the two masterpieces. By 1959, Alwyn had become interested in dodecaphony. The String Trio, in four compact movements, is the most fully realized result of that interest. Characteristically, he doesn't do the full serial Monty, for while tonality may at times hover ambiguously, at others, you can definitely hear a key. Unlike total serialists (Babbitt, for example), Alwyn does not build his music or his basic row by combinatorial set principles. His rows, like Stravinsky's, have their roots in actual sound, rather than concept, and he uses the row not as the only foundation, but more as a melodic source. The string writing, the ensemble, bears the mark of a master. It's not an easy piece – any more than Beethoven's Op. 110 – but it does repay listening. This is one of my favorite Alwyns.

The latest piece, the Clarinet Sonata of 1962, I had not heard before. The language has become harsher, compared to works through the early Fifties, with emphasis on the tritone interval, the so-called "diabolus in musica," and on short cells, especially a set of repeated notes followed by a rising minor third. This cell generates other themes. Indeed, the tritone and the repeated-note cell furnish most of the material for the work. In one movement, the sonata begins on an anguished cry and little emotional light penetrates the movement. Even the slow and quiet sections are filled with trouble. The main rhetorical strategy is to begin big, fall back, and build back up, over and over. Although rhapsodic in its idiom, it takes the form of a modified sonata, with exposition, development, and recapitulation. The argument is extremely tight. This stands with some of the best sonatas for the instrument, and not just Modern ones either.

The performers have mastered these scores. I've tried to pick out the stars, but everyone here plays at such a high level, it makes no sense to do so. The recorded sound is superb. I consider this one of Naxos's outstanding releases – and all at a Naxos price as well.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.