The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Honegger Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

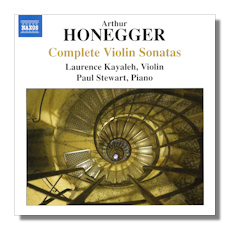

Arthur Honegger

Complete Violin Sonatas

- Sonata for Violin & Piano in D minor (1912)

- Sonata #1 for Violin & Piano (1918)

- Sonata #2 for Violin & Piano (1919)

- Sonata for Solo Violin in D minor (1940)

Laurence Kayaleh, violin

Paul Stewart, piano

Naxos 8.572192 73:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: A fine invitation to explore Honegger's chamber music.

Through most of the 19th century, French composers concentrated on civic spectacle and opera because, frankly, that's where the money was. The Parisian public especially had little interest in instrumental music. Those who concentrated on it, like Onslow and Saint-Saëns, either had independent means or secure, living-wage jobs. It takes the likes of Saint-Saëns, Franck, Debussy, Ravel, and the composers who comprised the School of Franck to begin to redress the balance.

Honegger, Franco-Swiss and to some extent an outsider, began his studies in Switzerland, where he became influenced by Reger and Strauss, at least harmonically. The first violin sonata, a student work sometimes designated "No. 0," comes from his twentieth year but exhibits a poise and mastery that many an older composer would envy. Some of the confidence likely comes from the fact that Honegger played the violin himself and well enough to perform publically. I'd love to know what his professors thought. The harmonies are post-Wagnerian, handled with assurance. The textures, lean and elegant for the idiom, eschew contrapuntal filigree. Believe me, you won't mistake this for Reger or even for German. Nevertheless, the tightness of the musical argument impresses me most. One finds very little filler. Even at this early stage, it shouldn't surprise us that Honegger became a symphonist. On the other hand, it's merely a very good conventional sonata, with little of Honegger's mature voice, but what else would you expect?

Not long after, Honegger entered the Paris Conservatory, where he studied composition with Widor and, more importantly, counterpoint and fugue with the remarkable pedagogue André Gédalge, who probably turned out more great composers than anybody else on the faculty, including those hired to teach composition. There, he fell in with classmate Darius Milhaud, Germaine Tailleferre, Georges Auric, and Jacques Ibert. He and Milhaud became especially close and remained so throughout their lives. His music began to change. He went through a brief spell of Impressionism before turning to Stravinsky and, to some extent, Satie. He became one of the most prominent members of the new-music group Les Six (Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, Auric, Tailleferre, Louis Durey), promoted by Cocteau. Although he participated in several group projects, he soon moved his music in another direction, toward Modernism, monumentality, and Bach, a major influence.

Six years later, his official Violin Sonata #1 appears, and it differs significantly from #0. The French virtues of harmonic and contrapuntal clarity have increased, as has a certain moderation of expression. One not only hears some Debussy and Fauré, but also a bit of that streetcorner verve, so beloved by many of the members of Les Six. The first movement, a sonata, uses only three ideas, but you remember all of them. I can say the same of the presto second movement, a contrapuntal whirligig. The counterpoint does not serve as an end to itself but to increase excitement. The finale begins adagio over a repeating bass, technically called a ground. It moves to an allegro idea, similar to the main idea of the presto movement, which gets treated in pretty much the same fashion. The two ideas bump against each other and even sound simultaneously before the energy fades and we find ourselves back to a major-mode variant of the opening ground. The original version reappears, and we're out.

Violin Sonata #2 appears a year later, the most concise, as well as the most experimental, of the set. In many ways, it radically rewrites Sonata #1, with the same general character of the movements and the restricted kit of ideas. However, the harmonies tend to hover between two different key centers, F and B, and sometimes the music proceeds in both keys simultaneously. Honegger absorbs the radical postwar atmosphere, especially through his buddy, Milhaud, but gives it back in his own way. For one thing, Honegger intensifies the counterpoint – more of it and more complex, although as clear to the ear as water to the eye. Much of this transparency comes down to Honegger's gift, like Beethoven's, for memorable rhythms, which can then function motifically. In the first movement, for example, a little triplet runs through the entire texture. The main idea of the scherzo second movement is so easily identifiable a rhythm, that Honegger can commit Serious Counterpoint without the listener losing the thread. The finale stands a bit outside the main thrust of the sonata, mostly somber. For one thing, it's largely in a major mode and in one key at a time – a whoop and a holler to blow away the previous clouds. Beyond all this, one senses a large talent for drama, giving emotional substance to each movement and pointing to the stage and film composer to come.

Skipping ahead thirty years, during the Nazi occupation of Paris, we find French composers taking refuge in the past. Poulenc, for example, produces Les animaux modèles on the fables of La Fontaine. Milhaud, safely in America, writes the Suite française. Honegger lands in the universal and the abstract, with Bach a guiding star. The Second Symphony, a searing abstraction of the anger and depression of Paris at the time, ends with a blazing trumpet chorale that raises hope, à la Bach. The earlier solo violin sonata obviously refers to Bach's contributions to the genre. The solo string sonata strikes me as one of the toughest tests for any composer. Some very fine ones have run aground attempting it. It turns out that a coherent melody without some harmonic and contrapuntal support, especially in a highly chromatic idiom, is pretty tough to shape. Hindemith's and Reger's, for example, trudge, scrape, and eventually sink under their weight. Honegger, Bloch, Halsey Stevens, and Bartók become some of the few to communicate through the limitations. In fact, they seem to write as if the compositional problems don't exist. Like Bach, they convince you the genre is "natural."

The work has four movements: an aggressive march; a dignified, grieving sarabande; a mournful bourée and musette; and a leaping gigue, filled to the brim with double stops.

Laurence Kayaleh and her pianist, Paul Stewart, do well in the accompanied sonatas. In the Sonata #1, I prefer Joseph Szigeti and Roy Bogas, on an old Mercury LP no longer available (natch). Szigeti plays with more fire, more individual personality, and less respect, the last of which to me gets in Kayaleh's way. On the other hand, Kayaleh comes alive in the solo violin sonata. She realizes more is at stake here than notes. Overall, however, this seems to me the best current disc of Honegger's chamber music for violin, and it has the advantages of easy availability and the Naxos price.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.