The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Alwyn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

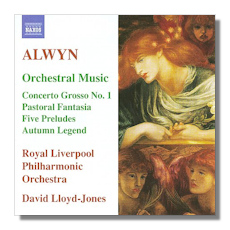

William Alwyn

Orchestral Music

- Overture to a Masque

- Concerto grosso #1 in B Flat Major

- Pastoral Fantasia 1

- Five Preludes

- Tragic Interlude

- Autumn Legend 2

- Suite of Scottish Dances

1 Philip Dukes, viola

2 Rachael Pankhurst, English horn

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.570704 DDD 68:24

Summary for the Busy Executive: Becoming and being.

From relative obscurity as recently as twenty years ago, the British William Alwyn seems about ready to break through to general awareness among the dedicated classical-music public, thanks in no small part to Naxos taking him up. The label has released a ton of Alwyn, not just the stuff already recorded, and furthermore, with the aid of the William Alwyn Foundation, has premiered many early works. In the Forties, Alwyn experienced a quantum leap in his music's expressiveness, which he attributed to his film work. He decided that much of his earlier output wasn't up to snuff and so withdrew or destroyed many of his scores from the Twenties and Thirties. In some cases, he might have done the right thing, but certainly not in all. Keep in mind that he became a professor at the Royal Academy of Music at the age of 21 and that his music had appeared under major conductors in major venues.

This CD mixes Alwyn semi-"hits" with the relatively unknown. The earliest score, the 5 Preludes, shows a young composer in need of an individual voice. Despite their considerable finish, they come across as sketches for something larger. The two works from the Thirties show him trying to find one, mostly by trying on various masks.

The Tragic Interlude shows Alwyn's explicit response to the waste of a generation in the First World War and reveals a big artistic sensibility trying to get out. One hears echoes of Elgar, the early Impressionistic Vaughan Williams, and Walton, as well as a determination not to let the influences overwhelm individual expression. That expression, unfortunately, never comes into strong focus. Nevertheless, this piece has over its entire span considerable power. Furthermore, one feels this not as a tragic costume put on, but as a grief-filled personal response.

Alwyn wound up with three acknowledged string quartets but had written many more. The Pastoral Fantasia reworks material intended for a String Quartet #13. It is a study in British Pastoralism, not terribly individual but lovely anyway. Moeran, rather than Vaughan Williams or Holst, seems the model. However, when one considers Alwyn's development, even in the near-contemporary Overture to a Masque, and what he would become, it strikes me as the work of a composer spinning his wheels.

Overture to a Masque sandwiches a Vaughan Williams-y lyrical bit between two brilliant stretches of sardonic Waltonian bubbly. It's extremely tight, all of the music coming from one two-part idea heard at the very beginning. The wartime Blitz cancelled its premiere, which got delayed for fifty years, five after Alwyn's death.

The Concerto Grosso #1 is a Baroque pastiche, à la Stravinsky's Pulcinella, but with original themes and from a neo-Romantic point of view. The opening, a vigorous dance, scored extra-lean, gets the blood hopping. The slow second movement, a Siciliano, sings tenderly, with just a tinge of regret. The third movement reprises the first movement's material but with a different treatment, and ends the work athletically. In this work, one hears the mature, assured composer.

The Suite of Scottish Dances, a throwaway, tips its hat to Alwyn's film work. The composer dedicated the score to Muir Mathieson, patron saint of British film music, who persuaded composers like Alwyn, Arnold, Bax, Bliss, and Vaughan Williams to write for the movies. Alwyn paints the traditional tunes in jewel-like colors. Unlike, say, the early 5 Preludes, this suite of miniatures is perfectly conceived and realized.

Autumn Legend, probably the best-known piece on the CD, was inspired by poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Alwyn was not only a fan, but a collector, amassing a fine Pre-Raphaelite collection when the group had fallen into neglect and prices were rock-bottom. He later sold his collection for a nice packet. There had to be at least a little self-identification, since Alwyn was a decent poet and painter himself, as well as a composer, flutist, pedagogue, and heaven knows what else. I also believe that his predilection for the Pre-Raphaelites revealed more of his artistic nature than he admitted. Beneath a thoroughly Twentieth-Century language lay a richly Romantic artistic soul. Normally, rhapsodic pieces inspired by painting, like Autumn Legend, turn me off. I usually miss the point, since I'm pretty much dead to the visual evocations of music. I consider Strauss's Don Quixote, for example, a masterpiece, but while I find the "visuals" fun, it's the music itself that excites me. It's the same with Autumn Legend. The cor anglais solos ravish me, as do Alwyn's orchestral colors. He wrote it in the middle of his symphonic cycle, a complete change of pace. Yet the habits of tight symphonic thinking still inform the score.

David Lloyd-Jones has produced a series that, with certain exceptions (Alwyn's reading of The Enchanted Island, for example), outdoes the composer's classic Lyrita accounts. The recorded sound is beautiful without stepping into the over-the-top. One of the best of Naxos's Alwyn collection.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.