The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Handel Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

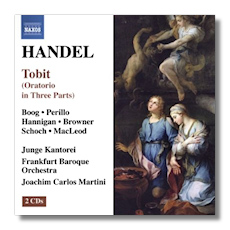

George Frideric Handel

Tobit

- Maya Boog (Anna)

- Linda Perillo (Sarah)

- Barbara Hannigan (Azarias/Raphael)

- Alison Browner (Tobias)

- Knut Schoch (Tobit)

- Stephan MacLeod (Raguel)

Junge Kantorei

Frankfurt Baroque Orchestra/Joachim Carlos Martini

Naxos 8.570113-14 DDD 2CDs 156:22

If you congratulated the shade of Handel about his oratorio Tobit, he would have shaken his head and not known what you were talking about. Like Nabal (Naxos 8.555276-77), Gideon (Naxos 8.557312-33), Redemption, and Rebecca (neither recorded yet, apparently, but don't lose hope!), Tobit is a pasticcio oratorio, assembled after Handel's death by John Christopher Smith from the late composer's pre-existing works. Smith took arias and choruses from Semele, Theodora, Ariodante, Rebecca, and others, and stitched them together, where needed, with new recitatives of his own devising. Sometimes the texts needed to be retouched as well. In Semele, for example, a chorus of Loves and Zephyrs takes a mythological and fleshly tack by singing, "Now Love that everlasting Boy invites/To revel while you may in soft delights." Smith (or rather, librettist Thomas Morell) cleans up that sentiment for pious ears by substituting "joy" for "Boy," and "pure" for "soft," and by assigning the chorus to the Israelites! All this might strike us as somewhat odd, but it was quite acceptable in 1764, the year in which Tobit first was given.

The story of Tobit comes from the apocryphal Book of Tobias. The titular hero, an Israelite, buried his friend Achior in defiance of the Ninevites. Tobit is persecuted by the Ninevites and suddenly is struck blind. In the meantime, his son Tobias and Tobias's friend Azarias journey into Media to collect on a debt. Tobias is saved from a giant fish (!), and falls in love with Sarah, who has been falsely accused of murdering her seven previous husbands. In time, Nineveh is destroyed and virtue is triumphant. Not only does Tobias return home with Sarah as his new bride, Tobit's sight is restored, and we also find out that Azarias really was the guardian angel Raphael. Compared to some of Handel's operas, quite a lot happens in the two-and-a-half hours allotted to Tobit.

Because Smith could pick among Handel's earlier works, the music in Tobit is (forgive the pun) particularly choice. Smith's accompanied recitatives are competent – at any rate, they don't drag the surrounding music down. Conductor Joachim Carlos Martini gets into the act too, although Keith Anderson's booklet notes are less clear about the role that he played in preparing this performance of Tobit, which probably was the first in more than two centuries.

This recording is taken from a live performance on June 3, 2001. Apparently Martini has made a habit out of presenting Handelian obscurities, because there are several other live Naxos recordings featuring this conductor, the Junge Kantorei, the Frankfurt Baroque Orchestra, and several of the soloists included here. Suffice it to say that if you liked Martini's Nabal, Gideon, Deborah (Naxos 8.554785-87), or Solomon (Naxos 8.557574-75), you will like Martini's way with Tobit. Martini takes a very traditional and sober approach, although he is not dull, and he is sensitive to Baroque performance practice. Also, some of his soloists are very delectable, especially sopranos Linda Perillo and Barbara Hannigan. One minor drawback concerns diction. English is not the first language of the chorus, nor of many of the soloists, and one is hard-pressed to understand what they are singing much of the time, unless follows the libretto… which one has to download from Naxos' website. Apparently there weren't even any make-up sessions scheduled, so what you hear is what the audience heard in the Kloster Eberbach, Rheingau, Germany, warts and all. Fortunately, there are not too many warts, but still…. Even occasional coughs and rustles from the audience have been preserved for all time. The engineering is neither dramatically good nor regrettable in any readily identifiable way. Some listeners have complained that the second CD – a full 80 minutes long! – does not track properly, but I had no problems with it on two different machines. This recording of Tobit, then, is more than a space-filler and less than a revelation. It is completely competent, for all the good and ill that implies!

Copyright © 2007, Raymond Tuttle