The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

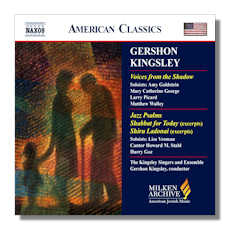

Gershon Kingsley

Judaica

- Voices from the Shadow (1997)

- Jazz Psalms (1966)

- Shabbat for Today (excerpts) (1968)

- Shiru Ladonai (1970)

Various soloists and instrumentalists

Gershon Kingsley, synthesizers

The Kingsley Singers/Gershon Kingsley

Naxos 8.559435 77:35

Summary for the Busy Executive: The Jazz Singer.

I first heard of Gershon Kingsley as part of the Moog synthesizer craze of the Sixties. Walter/Wendy Carlos had made a huge splash with the Switched-On Bach albums, and not just with the public. Composers became excited by the possibilities as well. At the time, the art of digital sound had been represented by the Columbia-Princeton synthesizer – essentially a room-filling computer with a musical interface. The results could be stunning, but the work staggering. One of my composition professors, with advanced degrees in mathematics, spent his summer vacation on a grant to work there. He fiddled around with dials and switches and perhaps punch cards from morn to dusk for three months and produced two minutes worth of music. He had to specify literally everything from the wave forms that produced the sound, the overtone series as well as the usual pitch, dynamic, and duration of each note. Columbia-Princeton was seen mainly as a dead end. Most electronic composers went back to such mundane things as tape-editing shortcuts, grease pencils and the like.

The Moog, on the other hand, allowed you to build, store, and access a library of sounds relatively easily. Rhythm, dynamic, and duration came down to a simple matter of pressing a key. It was still a shlep. A Moog "performance" was a bit of an illusion. You still had to splice bits of tape together, but overall you put up with less hassle. Some composers confidently (and a bit giddily, it turned out) predicted the death of the symphony orchestra.

Kingsley wrote a concerto for four Moogs (probably due to the performance limitations of a single instrument), I believe, for the Boston Pops – a performance I managed to catch on TV, back in the days when educational (as opposed to public) television really existed. Despite the futuristic hardware, the concerto was fairly conservative, and I liked it very much. Indeed, I'd like to hear it again before I die. Kingsley then popped up as musical director on a spiffy off-Broadway-cast recording of the complete Blitzstein Cradle Will Rock. Still later, Kingsley produced one of my favorite LPs – an arrangement for Moog and piano of Rhapsody in Blue as well as excerpts, popular and obscure, from Porgy and Bess. This was, for example, my first exposure to Gershwin's fugue that accompanies Porgy's fight with Crown.

Born Goetz Gustav Ksinski in 1922 in Germany, the Jewish Kingsley fled to Palestine in 1938, largely due to the efforts of American Zionist groups, on one of the last trains out of Hamburg. Fortunately, his parents also managed to get out even later, showing up in the United States via South America. A natural, Kingsley came to the formal study of music relatively late, having first played in jazz groups, or at least what Europeans called jazz. There has always been a "cross-over" element to Kingsley's work, or, rather, he has always tried to express completely what was in him, without regard for genres, for the most part successfully. As he himself put it, "Mozart dances with the Beatles." In 1946, Kingsley emigrated to the United States, where he has enjoyed a fairly busy career as a commercial musician – Broadway and off-Broadway, staff orchestrator for the old Vanguard label, arranging for the likes of Jan Peerce, becoming music director for Josephine Baker and Lotte Lenya, conducting at the Joffrey, and so on. He also came under the influence of composer Max Helfman, who had a Socialist vision of a reborn Judaism after the Holocaust. This strengthened Kingsley's populist musical inclinations. Kingsley courts popularity while remaining a fairly sophisticated musician.

Voices from the Shadow sets poems by victims of the Holocaust. All reflect, in some form, the minutiae camp life, and thus we don't get explicit grand didactic themes – a blessing. Many texts take off from folk forms. Kingsley has responded with music that sounds a little bit like Kurt Weill's – the sort of European pop played between the wars. The texts come in several languages – German, Yiddish, Czech, English, and French – and Kingsley somehow changes subtly the music's inflection with the shifts in language. From a technical point of view, Kingsley has set each poem well, but a listener might respond fully only to a couple in the total of seventeen. The music, for the most part, establishes a pleasant melancholy, with few shifts of mood. My favorite setting is probably the least populist, "Schlof mayn Kind," a lullaby with heavy overtones of Stravinsky.

The Jazz Psalms fare better, although they're not, as Kingsley is well aware, really jazz for the most part. Modal, lively, they remind me (if I had to guess) of a certain kind of West Coast jazz from the Fifties and Sixties. The score comes out of the Sixties concern for relevance (one of my least favorite aesthetic criteria) that also produced Bernstein's later Mass and, on the other side of the coin, bad folk-pop in liturgical services that continues to this day. For singers, soloist, and a jazz quintet, including two percussionists, flute, piano, and bass, the lion's share of instrumental solos goes to the flute. Kingsley does give the flute the opportunity for extended improvised solo in the "Hashkivenu." Kingsley produced an exceptionally good example of its kind, although you probably shouldn't compare it to Beethoven's Missa Solemnis or even to Amram's similar "Jewish" work from the Fifties and Sixties.

Shabbat for Today goes further in this direction. In its own time, it generated controversy, partly because of its use of synthesizers (seen then as a "rock" instrument) and partly because of Kingsley's collaboration with the Prince of Darkness Himself, John Cage, who replaced the rabbi with tape recorders. Things change, as they say. The music, at any rate, now seems a perfectly blameless setting of prayers for the Sabbath service – a cross mainly between Fiddler on the Roof and Hair. There's also a speaker part, not my favorite device, which could easily be dispensed with. The music stands on its own.

Shiru Ladonai ("Sing to the Lord") sets some more prayers, again in a kind of Broadway idiom. This was my favorite piece on the program. My preference comes down to a matter of liking these tunes more than others.

Irritations out of the way, next: Neil Levin's liner notes, like nearly all his others for Naxos' series on American Jewish music, are clumsily written and overblown. Rabbi Mortimer Leifman provides translations from the Hebrew with superfluous theological commentary and two ears of solid lead.

As conductor, Kingsley keeps things moving. Rhythms are sharp, consonants enunciated and crisp. Of the soloists, I liked soprano Lisa Vroman and Cantor Howard Stahl best. Vroman took an easy approach to Kingsley's jazz and pop rhythms, while Stahl has a ringing tenor. Overall, I can't call this an essential album, but it does have its attractions.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz