The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Giannini Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

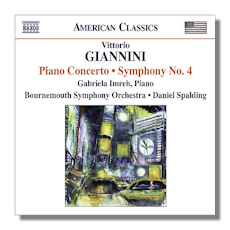

Vittorio Giannini

- Piano Concerto

- Symphony #4

Gabriela Imreh, piano

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Daniel Spalding

Naxos 8.559352

Executive summary: Richly expressive, heartfelt music, sympathetically performed.

As the dust settles from the hyperbole of music criticism of the last fifty years, we are beginning to take a look, from a more evenly balanced perspective, at the creative contributions of our American composers of the 20th Century, and judge that music on its own values and not on its place in the evolution of style. I would like to believe that it is judging music on its own worth, versus some stylistic notions of what might have been considered appropriate, is what has lead to this rediscovery of these works by Giannini.

Vittorio Giannini (1903-1966) is one of so many American composers who was overshadowed by the more revolutionary composers of his time. While his Piano Concerto received good notices on its première in 1937, it seems to have quickly. It was music of the 19th Century written in the 20th Century. Olin Downes, writing of the New York première, (given by the National Orchestral Association; Roselyn Tureck, piano; Leon Barzin, conducting) opined, "That the invention is operatic, rather than symphonic in outline, is true, nor need be claimed that this score, too heavily orchestrated and too elaborately treated for its material, has very much originality." I would agree with much of Downes wrote at that time. Surprisingly, he did not seem particularly critical of its conservative style. Downes also states, "The grand peroration at the end is à la Rachmaninoff." I am reminded of another work which received its first performance in the late 1920s and was severely criticized for being too conservative…Rachmaninoff's own Fourth Concerto! Perhaps Giannini's Concerto was not of its time either, but as Downes adds, "The first thing is spontaneity and directness of approach, and this the music has."

The first movement of the Concerto is a curious mix of styles. One is reminded of the music of Saint-Saëns, MacDowell; more Chopinesque than Lisztian. The movement seems a bit long as the thematic material tends to outstay its welcome. The second movement is, to my ears, far more successful. It is clearly a joyous romantic expression of a young man who is in love with the beauty of a singing melodic line. It is gloriously beautiful music. The shape of its thematic material, beginning at the entrance of the solo horn, its exposition and development, suggests to me the slow movement of the Saint-Saëns Third Symphony, a work which Giannini had likely heard when it was performed in New York in 1930, just four years before Giannini wrote his Concerto. From a structural standpoint, the rhetoric of the final movement of the Concerto is a bit long, but it is rich with a wealth of attractive thematic material. There is a fugato section which seems a bit out of place. I was expecting the final entrance of the subject to be on the piano, yet the piano only seems to offer a bit of comment on the development of the fugue subject.

The music benefits greatly by the playing of pianist Gabriela Imreh, who puts her obviously substantive technique and interpretive skills to good use. It is clear that she cares about the music and has all of the requisite skill to convey every ounce of its expression. The focus of her interpretation is on the intimacy and lyricism of the music as opposed to any attempt to maximize the bravura. One hopes that she will explore other concerted works of this same era, by the likes of Ornstein, Sowerby, E.B. Hill, Lopatnikoff, Gruenberg, Diamond, Cole, et al. While the Piano Concerto is filled with the rich expression and optimism of a young man, the Fourth Symphony written 25 years later, understandably presents us with a mature composer who is far more introspective and reflective. It is a richly melodic, inspiring expression. To my ears, the music is stylistically similar to the work of another superb composer of this same period of time, and, as of this writing, still composing; Robert Ward.

The slow movement is, for me, the heart of the work. It sings with great beauty. While I don't know if film composer John Williams had any training under Giannini, I feel as though I would be remiss if I did not mention the similarities between portions of Williams' magnificent score to Superman, the final third of the track, the "Fortress of Solitude" in particular, and the slow movement of the Giannini Fourth. I believe Williams did study at Juilliard around the same time Giannini wrote his Symphony so perhaps Williams was left with some imprint of Giannini's work. The Symphony's finale is full of nobility and strength.

Both Spalding and Imreh deserve great praise for bringing us superb performances of such highly expressive, heartfelt music. Spalding provides a respectful and well-balanced reading to the music. For my tastes he is a bit on the timid side when it comes to exploring the extremes of expression to be found in the music. His approach is most convincing in the slow movements. A tape of the first performance of the Symphony with Morel conducting the Juilliard Orchestra shows that a more vigorous interpretation can be quite effective, even if the quality of the ensemble was wanting, as was the case with the that first performance.

The playing of the Bournemouth Symphony is what this writer has come to expect of that organization…flawless. Expert program notes are provided by that champion of American Music, Walter Simmons. The recorded sound seems a bit distant. I would have also appreciated the piano sound being a bit more forward. Even with minor reservations, this disc is a major contribution to the Naxos series of American Classics.

Copyright © 2009, Karl Miller