The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

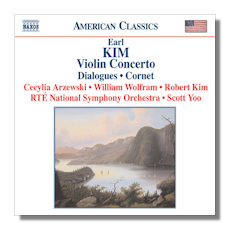

Earl Kim

- Concerto for Violin & Orchestra (1979)

- Dialogues for Piano & Orchestra (1959)

- Cornet for Narrator & Orchestra (1984)

Cecylia Arzewski, violin

William Wolfram, piano

Robert Kim, narrator

RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra/Scott Yoo

Naxos 8.559226 DDD 57:16

Summary for the Busy Executive: La gazza ladra.

California-born Earl Kim studied with Schoenberg, Bloch, and, later, Sessions. He taught composition at Princeton and wound up at Harvard. He died in 1998, age 78. He never broke through to the public, although he had the respect of his academic peers. To tell you the truth, I know only one other piece, a song recorded by Dawn Upshaw on her "Orange Lips" album, but I don't remember it too well. Few recordings of his music appeared, which means that I remain in the dark about much of his output. Aficionados know him for his Beckett settings.

The word on Kim is that, like Berg, he makes serialism lyrical. That applies to only some of the pieces here, as we shall see. The description misses the point. Kim's music often sings, but not necessarily serially. One can hear echoes not only of Berg, but of Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky, and Mahler. For me, Kim is a magpie of a composer. He takes a bit from this one and that one. His saving grace consists of his ability to create a personal viewpoint out of the pre-fabricated pieces. For example, the violin concerto, written for Perlman, begins with shifting chords, probably all variants of a row, in the manner of Schoenbergian Klangfarbe ("sound-color"). This leads eventually through Webernian pointillism with Stravinskian rhythms and an Adams minimalism to a diatonic scalar passage straight out of neo-classic Stravinsky. The work consists of eight brief sections organized into two large movements. Throughout, one finds an intensity that I'd call austere, if ! it weren't so sonically beautiful. The composer forces our attention on only a few things at any one time, but he demands that we do indeed pay attention. I recall particularly a passage of alternating thirds, very Mahlerian, in the first movement that shows up in the second part as a Mahlerian arioso, of a kind familiar to those who know the song "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" or the adagietto from the fifth symphony. The music is made up of moments, brief, spare, and, again, intense. The orchestration shows a precise sonic imagination, but it paints in watercolors, rather than in oils. One doesn't find, for example, the density of Webern or Boulez. This is essentially chamber music with a lot of players.

For me, the concerto constitutes the major piece on the program. The concertante Dialogues for piano and orchestra, written two decades earlier, is a younger man's work. The Stravinskian elements show up more strongly, but not the Stravinsky of the roughly-contemporary Movements (1958-59), also for piano and orchestra, Instead, Kim leans more heavily on that composer's work from the Thirties and Forties. It's extremely well-written, and it shows Kim's characteristic elliptical expression. But it's less personal than the concerto.

Cornet, based on Rilke's Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christopher Rilke, is a melodrama – simultaneous music and recitation. I very seldom see the point of the genre in general. Usually, either the music is superfluous or the text is. You wind up wondering about the point of the exercise. Kim writes a well-crafted accompaniment, but the work as a whole doesn't escape the generic pitfall. I found myself wondering whether the work is for people who can't read Rilke without some sensory aid. Somewhere along the way, probably because the poem is so visual, I thought of it as a soundtrack for a movie that would never be made. But in all of these speculations, you see that the piece doesn't seem to have a life of its own, no matter how good the workmanship.

Cecylia Arzewski broke several hearts at Severance Hall when she gave up her Associate Concertmaster position in Cleveland to become concertmaster of Yoel Levi's Atlanta Symphony. She has impeccable technique and a true, though smallish tone, at least here. The Kim concerto calls on the violinist to play in two modes: as a chamber player and as a virtuoso. The textures, however, are so delicate that the soloist can't ramp up into Tchaikovsky mode without upsetting the ensemble balance. Scott Yoo and his Hibernians do very well indeed. Kim's textures are so transparent, you have no place to hide. They do particularly well in the Cornet, no small feat, since the level of simultaneous musical activity usually surpasses the other works. Robert Kim, the composer's nephew, takes on the role of the narrator, delivering a "natural," colloquial reading of Rilke's text. Under other readers, Rilke's poetic prose could cross the line into the unacceptably mannered and sink the ! entire enterprise into pure corn. Above all, the story comes across as a savage one, told against hellish landscapes.

The sound is good without calling attention to itself.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz