The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Moross Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

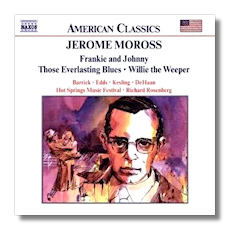

Jerome Moross

Urban Americana

- Frankie and Johnny 1,2

- Those Everlasting Blues 2

- Willie the Weeper 3

1 Melisa Barrick, soprano

1 Denise Edds, soprano

2 Diane Kesling, mezzo-soprano

3 John DeHaan, tenor

Hot Spring Music Festival Symphony Orchestra & Chamber Chorus/Richard Rosenberg

Naxos 8.559086 63:29

Summary for the Busy Executive: High times with low life.

American composer Jerome Moross comes out of the Thirties New York Left. He joined such lights as Elie Siegmeister, Arthur Berger, Bernard Herrmann, Vivian Fine, and Paul Bowles in a kind of composers' study group, under the guidance of Aaron Copland, to talk music and to go over one another's work-in-progress. Almost all of them faced a conflict between their artistic and political lives. At one time, almost all of them wrote in a hierophantic, aggressively Modern idiom, the kind that used to empty concert halls and now graces such popular entertainment as movies and commercials. On the other hand, they felt a duty to connect with the proletariat – the very folks who, if they listened to classical-music concerts at all, walked out or switched off the radio at the opening measures of Awful Modern Music. Well aware of the problem, they either ignored it (Arthur Berger), stopped composing (Ruth Crawford Seeger), or looked to vernacular music – American folk music, pop, jazz – for a way out. Critics usually credit Virgil Thomson for discovering the last. Aaron Copland writes an appreciative letter to Thomson and praises him for giving American composers "a lesson" in how to use folk music without betraying their artistic consciences.

Moross resorts to the last path. The Naxos CD includes Those Everlasting Blues, an extended aria on the Alfred Kreymborg poem. Moross wrote it in 1932 at the ripe old age of 19, a student of the radical Henry Cowell. There are jazz elements in it, but highly abstracted, like a bit of newsprint in a Cubist collage or ragtime in an Ives sonata. I suspect many even today would find it a rough ride. In many ways, it typifies young man's music, especially in its desire to be taken very seriously indeed. But Moross quickly changed. Naxos' inclusion of it in the program shows how very far, very quickly Moross went. By 1935, he hits on his trademark mix of blues, proto-jazz, vaudeville songs, folk music, and camp songs. The new music has the efficiency, elegance, and geniality of Mozart, never inflated to bathos. It entertains like a Broadway show.

Moross wrote the ballet Frankie and Johnny in 1938 for the Chicago choreographer Ruth Page. It wittily mixes dance with song. A trio of Salvation Army "savin' Susies" comments on the action with raunchy, low-down, Mae-Westian take-offs on the well-known bluesy, blowsy tune. Frankie works herself up to a jealous rage and shoots her lover to, if you listen carefully, very Modern music indeed. I was struck this time around to expressive devices borrowed from Stravinsky and Ives. But you don't think of either Stravinsky or Ives. You hardly think at all, because you're too busy getting the socks charmed off your feet. This is at least the third recording of Frankie I know of (the first, originally on a Desto LP and transferred to Bay Cities CD1007, conducted by Hendl; the second by Falletta and the New Zealand Symphony on Koch 3-7367-2), and it's got a lot to recommend it. Falletta and the New Zealanders may play more symphonically and more precisely than Rosenberg and the Hot Springs Music Festival, but the Americans seem to have more fun.

For me, Willie the Weeper gives the most pleasure, not least because it's new to me. As far as I know, it gets its first-ever recording, definitely the first in its orchestrated version. It forms the second part of Ballet Ballads (1948), a triptych of ballet one-acters by Moross and librettist extraordinaire John Latouche. The trio of dances (Susanna and the Elders, Willie the Weeper, and The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett) appeared first off-, then on-Broadway to great acclaim. I don't believe any of the trio has ever appeared in commercial recording until now, which kind of lets you know the shelf life of great acclaim. Until now, I've only read about the Ballet Ballads in books. Keeping in mind the economics of off-Broadway, Moross provided a piano-vocal score but always intended to orchestrate the dances. What with one thing and another, however, the opportunity didn't arise until 1966, when CBS paid Moross to orchestrate Willie for a show which never aired. Obviously I can't speak to the other two parts, but Willie's a knockout. As in Frankie and Johnny, Moross mixes song and dance, but here even more elaborately, calling for a tenor and chorus, with either solo or chorus in every movement. Moross remarked that he wanted "to so mix the singing and dancing that you didn't know where the singers began or where the dancers ended." Alert listeners will recognize the links to Weill and Brecht's Seven Deadly Sins. Indeed, as with Brecht's Singing Anna and Dancing Anna, we find a Singing Willie and a Dancing Willie, representative of two places in the character's psyche. The plot tells about Willie and his reefer, "the magical weed" which allows him to escape his dreary life into fantasies of wealth, power, sex, and (pathetically) even simple acceptance. Latouche bases his text on a couple of urban folk rhymes, "Willie the Weeper" and "Cocaine Lil":

Did you ever hear about Willie the Weeper?

Made his livin' as a chimneysweeper.

Cocaine Lil, Cocaine Lil.

She lives in Cocaine Town on Cocaine Hill.

She has a cocaine dog and a cocaine cat,

and they fight all night with a cocaine rat.

Moross comes up with a score that pays homage to the twelve-bar blues and to boogie-woogie. Almost all the music varies these forms, with the exception of two "pop" numbers, one foreshadowing the later Moross-Latouche musical, The Golden Apple, beloved of Broadway cultists, toward the end. The work opens and ends in a rolling marijuana haze. Along the way we get frenzied blues, seductive blues, sad blues, and so on. The blues, of course, has a definite harmonic structure, and Moross amazes me with the modulating changes he comes up with, still in the spirit of the blues. At one point, I suspect he's in two keys at once or dancing on the edge of a shimmering divide between two keys. Latouche comes up with so many wonderful lyrics, it's hard for me to decide what to quote. At random, I've picked the following from the episode "Famous Willie":

In Turkestan, in Kansas City, Kan.

In Moxie or Biloxi who's the favorite man?

Who's the chap who is the apple of the pub-a-lic eye?

It's twelve-tone Willie when he hangs it high.

But there's also Cocaine Lil's enchantingly syncopated refrain:

'Cause it's oh baby, and gee baby,

And m-m-m baby, and ah,

And it's well, well baby, and swell baby,

Then good-bye baby, good-bye, ta-ta.

Obviously, both Moross and Latouche intend something at least a bit satiric, but Moross's music humanizes it. It gets us to genuinely care about poor Willie, even as he sinks back into stupor.

The Hot Springs Music Festival Symphony Orchestra mixes, as a matter of mission, professionals with students, and, to some extent, it sounds like it. Intonation is professional, but attacks aren't particularly crisp. Nevertheless, Rosenberg does a fantastic job getting inside Moross's music. The student Festival Chamber Chorus has voices a bit young, but the diction and characterization of the words leave many a professional group in the dust. Everything has the happy energy of a Broadway show. Mezzo Diane Kesling scores a tour-de-force in Those Everlasting Blues. This ain't easy music, and she treads a fine line between an "operatic" and a vernacular approach. Unlike most classically-trained singers, including native speakers, she actually knows how to sing in English without sounding like Margaret Dumont or as if she's trying to swallow a mouthful of hot mush. It's a solid dramatic performance as much as a feat of singing. I can say the same for tenor John DeHaan in Willie. He comes closer to musical comedy than Kesling does, but his declamation isn't as crisp. Still, a fine job of singing and a fine performance as well.

The sound is quite good for each piece, but I do want to complain about the different recording levels between Those Everlasting Blues (recorded much higher) and the two ballets. A comfortable level for Frankie and Willie becomes slightly painful with Those Everlasting Blues. A comfortable level for Those Everlasting Blues makes you strain to hear the ballets. Other than that, a great CD, especially for the price.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz