The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Piston Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

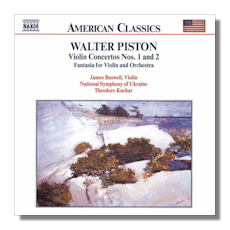

Walter Piston

Works for Violin & Orchestra

- Concerto #1 for Violin & Orchestra (1939)

- Fantasia for Violin & Orchestra (1970)

- Concerto #2 for Violin & Orchestra (1960)

James Buswell, violin

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Theodore Kuchar

Naxos 8.559003 60:49

Naxos' American Classics series scores another coup by releasing these works on CD. No competitive versions are available, and even if they were, the Naxos price tag would remain powerfully attractive. Better yet, the quality of the performances (and of the music itself) is gratifyingly high.

Walter Piston (1894-1976) was of Italian descent - "Pistone" was his family's original surname - and the Italian gift for melody can be heard in these three scores, as modern as they may initially seem. He was born in Maine, studied at Harvard and in Paris (with Paul Dukas and, like so many other composers, Nadia Boulanger) and returned to Harvard, where he remained on the faculty for almost 35 years. In that time (and for more than ten years after his retirement in 1960), he composed steadily, and he also found time to write several classic texts on music theory. He has been dismissed by some critics as a good academician, and it is true that his music is composed with exquisite care rather than with boundary-advancing imagination. Nevertheless, while some men must be out on the frontier, others need to stay in the settled territory nurturing and protecting hearth and home, and it is not to Piston's discredit that he did unsurprising things very well. Most of his music is tonal, but not in the 19th-century sense, and ambiguity (of key, of mode, of emotional climate) is a characteristic of his music. He said that his music sounded like the "same old Piston" no matter what compositional technique he used, and while there is some truth to that statement, it places him in excellent company.

The two concertos date from 1939 and 1960. Both are concise works, with hardly an inessential note. The first, believe it or not, is modeled after Tchaikovsky's sole work in this genre, although I don't think I would even begin to suspect this unless I had read it in Naxos' annotations. The first movement is full of Piston's typically shifting moods. The first theme is warmly lyrical in spite of its angularity, and the second is more cool. Like Copland, Piston cultivates a friendly, vaguely rural feel, but he is more sparing, more likely to hide his emotions. He builds to a heartwarming climax and then quickly cuts it off, almost in embarrassment. The second movement, a theme and variations, is similarly open-ended; the shape of the theme suggests a blues improvisation, even though the music is not jazzy. The finale is a bit of a barn dance, but there is more serious contrasting material before the concerto stamps to a friendly close.

The second concerto is darker. Nevertheless, this statement can be taken only so far. The first movement opens fretfully, but its second theme has the quality of an arrogant strut. Again, the middle movement is a set of variations on a theme. The theme has an oddly repressed quality, and the variations seem intent on dirtying it up a little. The finale, however, is almost unequivocally high-spirited. In essence, it's an angular dance with skipping rhythms and rich orchestration, and the lyrical, wide-intervalled second theme can't douse its optimism.

The Fantasia was written in 1970 for performance by violinist Salvatore Accardo. Accardo's affinity for the music of Bach and Paganini caused Piston to write music that had the emotional intensity of the former and the brilliance of the latter. Even so, this is a sad work, in spite of its title. Piston's biographer suggests that its outer sections are "painfully aware and transcendentally serene," and that the interior includes "a musical commentary on an overwhelmingly hectic world."

Violinist James Buswell has an apartment in Watertown, Massachusetts, across the street from Piston's grave. One can be sure that Dr. Piston is not rolling around in said grave as a consequence of these excellent performances. (Buswell, who plays a Strad, studied at Juilliard with Ivan Galamian.) Kuchar and his Ukrainian orchestra partner him idiomatically. These are not "good, considering" performances, but excellent at any price. Naxos' engineering is unobtrusive, that is to say, natural.

Copyright © 1999, Raymond Tuttle