The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Henze Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

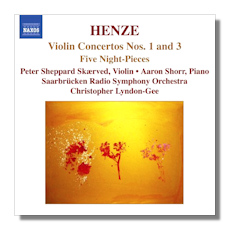

Hans Werner Henze

Violin Concertos

- Concerto for Violin & Orchestra #1 (1946)

- Concerto for Violin & Orchestra #3 (1997)

- 5 Night-Pieces for Violin & Piano (1990)

Peter Sheppard Skærved, violin

Aaron Shorr, piano

Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra/Christopher Lyndon-Gee

Naxos 8.557738 69:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: Yawn.

Along with Stockhausen, Hans Werner Henze became the most internationally-prominent German composer in the years immediately following World War II. Interest in his work peaked during the Sixties and Seventies, when (among other things) Deutsche Grammophon adopted him as its house composer with a series devoted to his work, as CBS had done for Copland and Stravinsky and Decca for Britten. Part of this attention may have come from the Marxist political component in Henze's work, although Henze never struck me as an especially political thinker, unlike someone like Hanns Eisler or even Luigi Dallapiccola. I thought of him as a fellow with his heart in the right place. That is, the message is more ethical than political. Come to think of it, I'd say the same about Eisler and Dallapiccola. Furthermore, this view really does ignore Henze's music – in other words, what we should judge a composer by – for some extra-musical message. Henze has plenty of "abstract" pieces – concerti, symphonies, and so on, whose source of inspiration isn't necessarily political. Nevertheless, that close attention waned as time went by. The interest of new-music fans went elsewhere: minimalism, Holy Minimalism, post-modernism, the Baltic, a younger generation of German composers, and so on. Today, Henze, although he hasn't lived in his native country since the early Fifties, has become the Grand Old Man of modern German music, apparently by default.

When it comes to Henze's music, I'm a hard sell. I can certainly understand the high regard in which others have held him. The music sounds beautiful – ravishing new sonorities, clear textures, easy-to-follow narratives. Hindemith and Schoenberg seem to meet in Henze. However, I feel as if I'm touching some handsome, highly-polished, smooth metal sculpture. There's a sensuousness to it, but also a chill. Everything seems nicely calculated. The music almost never gets inside me.

The compositional maturity of the first violin concerto impresses me the most. Henze wrote it at twenty, but you wouldn't be surprised if it came from someone thirty years older. The first movement poses the most problems: it takes a while for it to get going, but Henze does manage to give a fine second half. The second movement, a brief scherzo, supposedly came from the composer's experiences in the Second World War, but it never really cuts loose and comes across as genteel – a modern equivalent of Adam's "Dance of the Nixies" from Giselle. I like the slow third movement best, since I manage to really connect for the first time. Large stretches of the finale work to great effect, but for me the movement as a whole never really comes together.

The third concerto, written fifty years later, has its source of inspiration in Thomas Mann's Doktor Faustus. Each of its three movements stems from a character in the novel: Esmeralda, the prostitute; Nepo/"Echo", the hero's nephew; and Rudi, the virtuoso. Obviously, the composer has injected a programmatic element into the score, but can one enjoy the work without knowing the novel? After all, you can love Strauss' Eulenspiegel without really knowing anything about the "plot." In either case, others may find the movements evocative. You have to vibrate more closely to the composer's wavelength than I. As for its musical virtues, again I leave it to others. I hear it as a sack of generic Schmerz and Angst. Many composers could have, and indeed have, written something similar. The last remark also applies to the five nocturnes, a compendium of serial clichés. Far more engaging is the Pettersson second violin concerto – just as difficult, but white-hot with inspiration.

The performances I would describe as "committed" rather than "wonderful." In the third concerto especially, the orchestra plays muddy. Skærved gets through the music (hard violin tone) without throwing any special light on it. Moreover, one listens in vain for a transforming moment, something that keeps you from lapsing into coma. Points to Naxos for releasing this at all, if only for the first concerto, but you wish the project had turned out better. It may make you wonder what all the fuss over Henze was about.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz