The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weill Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

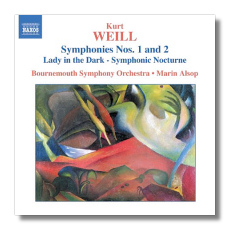

Kurt Weill

Symphonies

- Symphony #1

- Symphony #2

- Lady in the Dark - Symphonic Nocturne (arr. Robert Russell Bennett)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Marin Alsop

Naxos 8.557481 74:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: Weimar Jeremiah.

I have yet to get over the fact that Kurt Weill died at 50, after a 30-year career. Masterpieces began to appear just before his 20th birthday. Weill ranks as one of the great theater innovators and composers, but his instrumental works – the violin concerto, the b-minor string quartet, the Quodlibet, the cello sonata, the two symphonies – also deserve respect. Weill left purely instrumental composition behind in Europe, although "instrumentals" continued to turn up in his theater works, including his musicals. You don't have to look hard for the reason. Weill worked solely as a professional musician. He didn't seek out the shelter and support of the academy. You can starve in the United States trying to make it on symphonies and concerti. Musicals paid. Time is money.

Contrary to somebody like Adorno, I don't necessarily knock the commercial culture as trivial or antithetical to great art, but it does influence the kind of art we get. Sondheim writes musicals rather than operas. Our playwrights tend to be entertainers and comedians rather than poets or tragedians. Tom Stoppard isn't really possible in this country, except as an occasional treat for a niche audience. For that matter, neither is Shakespeare. Our concert composers, with few exceptions, work as teachers or even outside music, live on the rare government grant, conduct or perform, or have family money of their own. A composer who lives solely on his own musical work is necessarily a composer working in the commercial field. Quincy Jones knew a lot more music than he needed to produce a Michael Jackson album.

On his arrival in the United States during the Thirties, Weill quickly and shrewdly summed up the environment he would have to work in. That he did so with so few compromises amazes me. Nevertheless, the symphonies tease us with what might have been.

The first symphony (Weill did not number his symphonies, but I probably will, for convenience), sometimes known as the "Berliner," comes from a 21-year-old Weill at the very beginning of his study with Busoni. On the strength of it, Busoni accepted him into his master class with the proviso that Weill do remedial contrapuntal work with Busoni's former pupil and assistant Jarnach. Listening to the first symphony, I don't quite understand why Busoni insisted, since the main problems with the score don't lie in the counterpoint. Weill's maiden effort doesn't completely succeed, but its virtues outweigh its defects. Above all, you remember its main ideas and despite the influence of something like Schoenberg's chamber symphonies, it sounds like nothing else at the time. It may flummox those who know Weill's later work, like the Dreigroschenoper, since it has little to do with fox-trots or German Kabarett style. Nevertheless, one hears foreshadowings, mainly in the harmonies (early on, he had a fondness for an added 6th in a triad, as in "Mack the Knife"). It may have its origins in a poem by Johannes Becher, at the time a religious socialist. Weill, a liberal who did not completely embrace socialism and was throughout his life attracted to material with strong moral and humanistic content, at one time affixed a quote from Becher's Workers, Farmers, and Soldiers: A People's Awakening to God to the symphony's title page.

In one movement, the symphony begins with a long introduction initiated by a descent of grinding chords. After a brief quasi-religioso section, it launches into an episodic allegro. The grinding chords reappear. We move to a long slow movement, a pokey Ländler (likely inspired by Mahler), and wind up with a "chorale fantasy" and a coda, based on the grinding chords. The emotional tone is surprisingly adult in one so young. However, Weill's inexperience betrays him, particularly in the first movement. There's no real argument, rather a series of loose passages. Things perk up afterward. However, the orchestration tends to thickness. Still, many a "mature" composer can reasonably envy the youngster for this score.

The Symphony #2 comes from Weill's brief stay in Paris. Commissioned by the Princess Edmond de Polignac (née Winnaretta Singer, heir to the sewing-machine fortune), Weill wrote the work in 1933-34, which became part of a long line of distinguished works commissioned by the Princess, including: Stravinsky's Renard, Poulenc's Aubade and organ concerto, Satie's Socrate, and Falla's El retablo de Maese Pedro. For my money, it reaches the level of Modernist musical icon, meticulously crafted, innovative, and way more memorable than most. By this time, Weill had mastered his Europop-based idiom. This symphony revisits the musical world of Mahagonny. The themes are clear-cut and song-like. The argument proceeds with neoclassic clarity, and early movements comment on later ones.

In three separate movements – the traditional fast-slow-fast, with the middle movement bearing most of the emotional weight – the symphony begins on a scalar idea rising through a minor third. This has great consequence throughout the symphony. Minor thirds, rising and falling, make up many of the themes and keys often shift by minor thirds. After a slow introduction with a stuttering undercurrent of quick notes, the quick notes gather together and burst out into a restless allegro molto. Weill holds the movement together by distinctive rhythmic motifs as well, many of them reminiscent of quick passages in Mahagonny, like the opening to the opera and the typhoon sequence. Lyrical contrasts show similarities as well with Mahagonny's "Und wie man sich bettet, so liegt man" ("as you make your bed, so must you lie"). It turns out that this shape appears in the other movements as well. I have no idea whether Weill thought of this consciously or subconsciously, but if we consider that he was on the run from the Nazis, it could stand as a prophetic warning.

The second movement is mainly a slow march, again held together with distinctive rhythms. The first theme is headed by a decorated falling third, also varied as a rising third. A trombone solo comes in with the ghost of "Und wie man sich bettet," which Weill then develops with great subtlety. Bits from the first movement creep in, slowed down, like brief flashes of memory. The movement moves slowly but inexorably and builds to several climaxes. It skillfully builds and, just as skillfully, falls away. After a final climb and climax, the movement's opening theme returns, subdued, and fades out.

Not a rondo so much as "rondo-like," the finale gives us back much of the first movement in a fun-house mirror. Despite "merry" rhythms, irony outweighs joy. If George Grosz had done animated cartoons, this music could have provided the soundtrack. The initial theme is simply the very first idea of the entire symphony sped up. Other ideas from previous movements join in, this time as grotesques. "Und wie man sich bettet" appears once more, this time as a quirky, perky march. The symphony ends, not on a grand high or on a note of reflection, but on a kind of horse laugh.

I saw Robert Russell Bennett's name as the "arranger" of the Lady in the Dark concert suite, and my heart sank. Because of a union rule as well as the lack of training of most Broadway composers, orchestration almost always fell to a talented group of scorers including Hans Spialek, Will Vodery, Don Walker, Hershey Kay, and, most famously, Bennett. We owe the sound of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, among others, to Bennett. A pupil of Nadia Boulanger, Bennett was a creditable composer in his own right, but no Kurt Weill. Weill had received special dispensation to orchestrate his own stuff, which he did. Incidentally, Bennett also came up with the Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture. Admittedly, it made a huge pops success (which I'm sure the Gershwin family and estate appreciated), but to me, it trivializes the opera. He was no George Gershwin either, and his effort kept Gershwin's far more interesting Catfish Row suite from getting a hearing. What's wrong with Bennett's "symphonic nocturne" is that most of it sounds not like Weill, but like Bennett. The "Dance of the Tumblers" movement comes closest, but it's still too suave by half. The original has more acid. Alsop would have done better to approach Kim Kowalke at the Kurt Weill Foundation for permission to present a scene of the real stuff.

On the symphonies, Alsop does a fine job indeed. For me, the two main previous recordings were Gary Bertini and the BBC Symphony on EMI (not currently available) and Edo de Waart and the Leipzig Gewandhausorkester on Philips – both, I believe, from the Sixties. Each has its virtues, although I slightly prefer Bertini (more Expressionist), but they both pursue the same kind of reading – edgy, even brutal. Alsop relaxes a little, allows in more warmth, particularly in the second's slow movement. The sound improves on the 50-year-old stereo, particularly of the EMI LP, and with Naxos, of course, the price is right.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz