The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

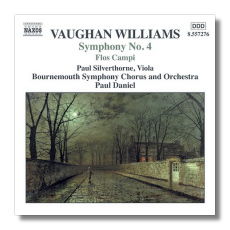

Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Symphony #4

- Flos Campi *

- Norfolk Rhapsody #1 in E minor **

* Paul Silverthorne, viola

** Stuart Green, viola

* Bournemouth Symphony Chorus

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Paul Daniel

Naxos 8.557276 62:34

Summary for the Busy Executive: Tremendous Fourth. Cool Flos.

Another entry in what may become a Naxos Vaughan Williams cycle, featuring the conductor Paul Daniel. Daniel led a very good, if not especially deep, account leading roughly the same forces in Vaughan Williams' "Sea" Symphony (#1), with the chorus standing out. Here, he betters my opinion of him as a champion of this composer.

In some ways, VW's Fourth Symphony is more graspable for conductors than symphonies like, say, the Second, the Third, or the Ninth. For one thing, among the composer's symphonies, it probably lies closest to a standard symphony, at least in its large architectural details. It also lies closest to the Modernist mainstream. Accordingly, you have very good performances by conductors not normally associated with Vaughan Williams' music – like Bernstein, for example. This may arise in part from the work's genesis. The composer began to write the score after reading a newspaper article on the modern symphony. Vaughan Williams' symphonies, like Elgar's, have in them all an intractable personal, idiosyncratic core, hard to crack. In my opinion, the Fourth has less of it than the others.

Nevertheless, you can't call the symphony a pushover. Thematically, it's the composer's most complex, built from a small kit of cells that, like Lego blocks, combine and recombine into new themes and ideas. The cells show up in every movement, establishing intricate interrelationships, mainly through headily-difficult counterpoint. Furthermore, rhetorically, the symphony, in four movements, comes to a full stop only at the very end. The first movement ends in a major-minor ambiguity, and the second on an unstable dissonance. The third doesn't really end but slams into the fourth, while the fourth passes up many opportunities to end before its last savage stamp. More than any other of Vaughan Williams' symphonies, the Fourth is conceived as a structural whole.

I've thought of Daniel's "Sea" Symphony as clean and efficient, rather than as deep or with strong affinities to the late Romanticism of Elgar and Parry. Those qualities come even more to the foreground in his account of the Fourth. However, they suit this symphony. Tempos tend toward the quick side, without losing crispness, and the reading moves breathlessly along. The account may lack some of the drama one gets in other recordings, but for seeing the symphony as a whole, no reading comes close to Daniels. For once, we don't a "war-prophecy-symphony" subtext, but the unfolding of practically pure symphonic discourse. The score can certainly take it. I consider this an essential performance.

The Norfolk Rhapsody #1, the only one of the composer's Norfolk Rhapsodies to have survived, comes from 1906. As with any VW piece I haven't heard, I wonder why he buried the other rhapsodies. Some ideas have occurred to me. The piece consists of an introduction, separate elaborations of two folk-songs – "The Captain's Apprentice" and "The Bold Young Sailor" – and a coda based on the introduction. The two most remarkable sections are the intro and coda, where Vaughan Williams demonstrates his gift for orchestral sonority. It's essentially his take on French Impressionism (just before his studies with Ravel). However, instead of a haze of notes from a lot of instruments, we get roughly the same effect from two or three extremely well-chosen ones. "The Captain's Apprentice," one of the most powerful of English folk-songs, follows. However, the composer doesn't tap the power. It's a fairly conventional treatment, given what the composer would do (and had already done). Indeed, VW's earlier setting for piano and voice beats the more elaborate orchestral version hollow. "The Bold Young Sailor" gets somewhat perfunctory treatment. But VW produced the same sort of music just three years later in the masterful overture to The Wasps. I would guess that the approach he had taken in the rhapsodies failed to satisfy him, and, indeed, I believe the composer revised the work after World War I, along with the similar In the Fen Country. I will say, however, that Daniels's recording easily surpasses any other I've heard.

The score of Flos Campi, based on sections from The Song of Songs, can easily deceive you. It looks so simple on the page. Indeed, many of the themes toe the line between simple and simple-minded, without ever slipping over. Yet, apparently it's a bear to bring off. There are many abrupt tempo changes, even within sections, and one finds the interpretive groove with difficulty. Matthew Best and violist Nobuko Imai have a devil of a time on Hyperion, for example. David Willcocks and the great Cecil Aronowitz give a good baseline performance, but (surprising for these artists) nothing really special. That's given to us by Richard Hickox and Philip Dukes on Chandos and by Daniels and Paul Silverthorne. The work has always struck me as compulsively strange, its simple surface yielding something highly enigmatic and elusive. The music runs from downright odd (the famous opening in two simultaneous keys) to passionate to barbaric to ecstatic. To many, it's a choral work, but the singers function purely as another orchestral section. The composer features the viola (his own instrument) but has written neither concerto nor suite. Damned if I know what it is, but when it works, it surely churns up your insides. Daniel takes what I consider a fresh look at the score, relating it more to the experimentalism of the Twenties than to the usual English Pastoralism. Silverthorne, for my money one of the great string players and a superb musician besides, turns his part into a marvel. Every line is gorgeously carved and shaded, every turn of mood caught. The final "Set me as a seal" section practically brought me to tears, as I'm sure the composer meant it to. Hickox takes a more traditional, though equally valid route, and Dukes I think equals Silverthorne. Ideally, you want both performances. Strange that two magnificent recordings of this work should have appeared so closely together.

Highly recommended, a must for the composer's fans.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz