The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Myaskovsky Reviews

Weinberg Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Soviet-Era Violin Concertos

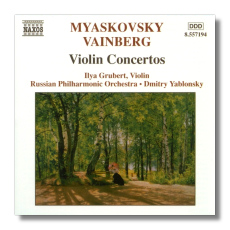

- Nicolai Myaskovsky: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 44

- Mieczysław Weinberg: Violin Concerto in G minor, Op. 67

Ilya Grubert, violin

Russian Philharmonic Orchestra/Dmitry Yablonsky

Naxos 8.557194 DDD 66:49

Here are two Soviet violin concertos that are starting to become better known. Westerners have mistrusted Nikolay Myaskovsky (or "Miaskovsky") somewhat, perhaps, because he was too prolific – nearly thirty symphonies! The work of Mieczysław Weinberg (or "Vainberg") is becoming generally more familiar. Chandos, for example, has embarked on a symphony series, whose first release I will be reviewing shortly.

The Myaskovsky concerto was premièred in 1938 by David Oistrakh. Apart from Grubert, its most recent advocate is Vadim Repin, who recorded it with Valery Gergiev for Philips (473343-2). In spite of its late composition date, this is largely "Old School" Romanticism, not far removed from the works of Glazunov and Glière. There is hardly a trace of Socialist Realism in this concerto, which seems blithely unconcerned about the world around it. The first movement often doesn't even sound particularly Russian. This movement, marked Allegro ed appassionato, accounts for more than half of the concerto's 38-minute length. There is a longish cadenza that is well-integrated into the movement's thematic structure. The middle movement is an uncomplicated and… songful Adagio molto cantabile, and finale, Allegro molto, is similarly primary – albeit attractive – within its emotional palette.

Weinberg (1919-1996) was a Pole who fled his homeland in 1939, not emigrating to the West like many, but east to the Soviet Union. He was mentored both by Myaskovsky (who was almost forty years his senior) and by Shostakovich, who intervened when Weinberg was arrested in 1953 for being an "enemy of the people." Shostakovich sometimes praised the music of card-carrying Communist composers who weren't fit to kiss the cuffs of his trousers, but his appreciation of Weinberg feels like the real thing. No surprise, then, that Weinberg's 1960-ish Violin Concerto bears many stylistic resemblances to Shostakovich. The mood is sardonic and tinged with bitterness, the themes are slashing and angular, the scoring is brittle, and the concerto chugs along like a Soviet newsreel. The Adagio third movement is touched with bleak lyricism. Even its four-movement structure is reminiscent of Shostakovich's First Violin Concerto, which was just a few years old at the time. Leonid Kogan premièred the concerto. It seems not to have had much exposure in the West.

Grubert is a sweet-toned violinist who must be in his late 40s or early 50s. His teachers included Leonid Kogan, so he has a special connection with the Weinberg concerto. He has the guts for the more physically demanding passages in these works, but he excels in the quieter moments, where his rapt playing commands attention. Yablonsky and the Russian Philharmonic give Grubert excellent support. (The Orchestra began as a recording ensemble drawn from Russia's best musicians, but it now has a life of its own.) The engineering is excellent – Russia has come a long way from the primitive recording technologies of the 1960s and 70s.

This is an excellent coupling. (Most recordings of the Myaskovsky pair it with another concerto you're likely to own already.) Don't hesitate.

Copyright © 2004, Raymond Tuttle