The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Penderecki Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

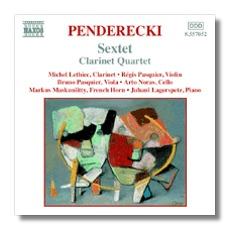

Krzysztof Penderecki

Chamber Works

- Sextet for Clarinet, Horn, Violin, Viola, Cello & Piano (2000)

- Clarinet Quartet (1993)

- Three Miniatures for Clarinet & Piano (1956)

- Divertimento for Solo Cello (1994)

- Prélude for Solo Clarinet (1959)

Michel Lethiec, clarinet

Régis Pasquier, violin

Bruno Pasquier, viola

Arto Noras, cello

Markus Maskuniitty, horn

Juhani Lagerspetz, piano

Naxos 8.557052 DDD 67:48

Summary for the Busy Executive: Very moving.

With only a couple of exceptions, most of Penderecki's chamber music comes from the first or the latest part of his career. The period of work he's best known for – his avant-garde years, with scores like the Threnody and the Passion According to St. Luke – has almost no chamber music in it at all, the composer concentrating on items for large forces. The early chamber music, from the Fifties, shows traces of Bartók, a tremendous influence at the time among the more talented composers of Eastern Europe. In the work of the last twenty or so years, the influence, though still present, has been completely absorbed.

The big work on the program, the Sextet, shows the mastery of an original voice. Penderecki, unlike many former radicals, doesn't repent. One still hears the debt to his own Threnody phase in various passages, but he has brought that rhetoric in line with more traditional procedures. Indeed, one also hears echoes of his early, Bartókian work. In short, in his latest work Penderecki has achieved stylistic integration.

The composer lays out the sextet in two large movements, with the second movement about twice as long as the first. An outstanding feature of the work is the instrumentation: clarinet, French horn, piano, violin, viola, and cello. It affords a wide range of color – wind, brass, strings, and percussion. It tends to give off a big sound, more like a small orchestra than the intimacy of most chamber groups, and Penderecki sometimes writes for it as if it were an orchestra, pitting masses against masses, or juxtaposing planes of sound, rather than striving for the conversational interplay of individual voices. The first movement, a tromping, acidic dance – "peasant" music stylized in a Bartókian way – becomes increasingly frenzied, with little islands of rest, as the music gathers up its breath for another whirl. The end of it summarizes the two main rhetorical elements – the tromp and the whirl, before ending on the whirl. The second movement begins with a long introduction, before it settles into a lament. The lament gets interrupted three times in the course of the movement with more jagged, faster music, but these storms soften with each appearance, while the lament becomes more singing, heartfelt, and – I'll say it – noble. Throughout, Penderecki's superb sense of instrumental drama keeps things moving and interesting. On their face, these are very simple strategies, and yet one confronts a work of unconventional and thoroughly convincing shape.

The slightly earlier Clarinet Quartet, on the other hand, is terse and tight, and as nearly as I can tell, monothematic. We've traveled a long way from the sprawl of Penderecki's middle period. Again, Penderecki comes up with an usual structure: three "bagatelle" movements preceding a "farewell" larghetto, longer than the three other movements combined. The first three movements, though stunning, appeal more to my intellect than to my passions, unlike the sextet. All the "heart" of the piece comes in the final movement. One finds oneself in an extended Mahlerian, Lied von der Erde moment, which seem to suspend time. Indeed, hardly anything at all seems to happen, and yet one is moved all the same, like looking out over a still lake and held by the occasional ripple. To me, this shows a master composer: eight minutes of incredibly slow which keep your interest.

Although very well-written, the other three pieces on the program don't aim as high. The Three Miniatures for clarinet and piano are a little fast-slow-fast suite, again heavily indebted to Bartók's take on folk music, especially in the last movement. The Prelude for solo clarinet carries off the feat of filling a compelling four minutes with just one melody instrument. Penderecki doesn't even get to write the occasional chord, as Bach does in his suites for solo strings. Paradoxically, Penderecki's Divertimento for solo cello, written for Rostropovich, does less with greater resources at hand. I find this the weakest piece on the disc. To me, it comes across as noodling around. Your mileage may vary.

I've no such reservations about the performances. The players work as one – smooth, even suave when called upon, and deliberately rough where they need to be. Above all, they convey the shape of entire movements without sacrificing the drama inherent in Penderecki's artistic makeup. The recorded sound is a little harsher (brighter) than I like it, but in all this is one of best Naxos releases I've heard, an outstanding item in the company's intriguing catalogue.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz