The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bax Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

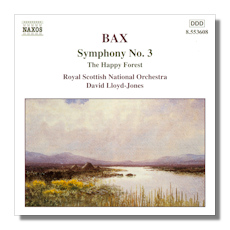

Arnold Bax

- Symphony #3

- The Happy Forest

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.553608 53:33

Summary for the Busy Executive: Dark skies, bright Springs.

During the Twenties and early Thirties, the British considered Arnold Bax the Next Elgar and went so far as to make him (to his considerable surprise) Master of the King's Music. It turned out that Elgar stood alone. Bax's music was something other.

I must admit that I didn't always admire that music which, to this day, interests me less than the composer's life and personality. For one thing, as he grew older, he composed less and less, critics hold the late works in less esteem than the early and middle, a judgment I don't necessarily agree with. For me, Bax fascinatingly combines the Modernist desire to "make it new" within an essentially late-Romantic viewpoint. I believe he once said (when it was highly unfashionable), "I'm a brazen Romantic….my music is the expression of emotional states." Music was supposed to be "objective." It could not express anything but "itself." This, by the way, is a crock. If it were true, dramatic music would not be possible, or rather it would make no difference whether Siegfried's journey to immolation occurred against the backdrop of his Funeral March or "How Much is that Doggie in the Window?"

The Third Symphony, the one I most wanted to hear, became the last I heard. At the time, the tone poems on which Bax's reputation rested (The Garden of Fand, Tintagel) left me cool and unwilling to explore any further. However, a Vaughan Williams freak, I read that VW had quoted a bit of the Third in the original version of his Piano Concerto for Bax's mistress, the pianist Harriet Cohen. He later excised the quote, feeling that nobody seemed to "get" it. I couldn't understand why VW would want to quote Bax, even to Harriet Cohen. I could discern nothing in common between the music of the two men. However, other symphonies and works came my way. I really liked the Second, Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh, which started to change my mind and made me ever more eager to hear the Third. Chandos came out with an account by Bryden Thomson, but Thomson I usually felt too sugary, certainly the way I'd describe this particular reading. Vernon Handley tempted me, but his account was available only in an expensive Chandos boxed set. I liked Bax, but not to the extent of wanting to acquire different recordings of the same scores. Naxos, with David Lloyd-Jones, offers a fine, inexpensive alternative.

Completed in 1929, the massive Third was at one point Bax's most popular, but so low had his reputation sunk by the time of his death in 1953, that at least through the early Sixties hardly anyone performed his major works. To some extent, postwar serialism had made serious discussion of the interwar generation uncool. However, Walton and Vaughan Williams continued to be the subjects of popular recordings, and not just through their lollipops, even as Bax faded from general consciousness. The VW symphonic cycle, for example, received three major recordings: Boult on Decca and EMI, Previn on RCA. Nothing similar happened to Bax. It took another twenty or thirty years for him to begin to come back.

The Third is in the three traditional movements: fast-slow-fast. The first movement in particular shows Bax's individual formal thinking. It's sort of a sonata as well as an A-B-A rhapsodic form. There is no formal development section, for example, because Bax continually develops his motives. What appears in the spot usually reserved for development is the exposition of the second subject. This is followed by a free recap. However, the architecture usually has little to do with the emotional effect of the work. Far more important is the rhetorical flow. Landscape inspired much of Bax's work – the more remote and wild, the better. Bax wrote his Third in the north of Scotland, and I, at any rate, hear the North Sea in it – turbulent waters, cold light. The first movement runs as long as some symphonies. It begins with a remarkable passage for solo winds tinged with orientalism – a theme based on what I think of as the "Jewish riff" (G – A-flat – B). This provides most of the matter for the first movement. However, a subsidiary line in the bass also gets raised to thematic prominence and provides lyrical contrast. The movement builds to two intense climaxes, only to fall away and then rev up at the end. In all of its considerable skill and depth of feeling, however, there's little definition in the artistic profile – the impression that this is a work by somebody in particular. You have only to compare this to a movement by Elgar or Vaughan Williams to hear the difference. With either, you know within a few bars at most who wrote what or at least who's imitating whom. Bax, on the other hand, despite his poetry and skill, sounds like a lot of people.

The gorgeous second movement shows Bax, I think, taking his own view of British Pastoralism. He works with pentatonic ideas, combining them with his native chromaticism, but in a way completely different from Vaughan Williams. There is, nevertheless, one brief passage that could have come from VW's Third Symphony.

The finale opens with a jaunty rondo, with elements of the grotesque and more than a few similarities to both VW's Fourth Symphony and Rimsky-Korsakov's Russian Easter Overture. I don't believe this a matter of conscious "cribbing," especially since the VW, I believe came later. Rather, the idea has become so much a part of the composer's psyche that he uses it almost unconsciously as the most appropriate thing to say at the time. Furthermore, Bax's tight grip on his development make such things natural outgrowths of previous strands of thought. The main formal novelty here is the "Epilogue," whose main theme Vaughan Williams quoted in the original version of his Piano Concerto. Some writers have hinted that it looks back on the previous movements, but if so, I haven't caught the references. It does, however, make a satisfying end to the symphony, begun in anxiety, a lovely, serene, almost other-worldly note. Bax carries off the trick of moving from one to the other seamlessly.

Substantially composed in 1914, The Happy Forest finally appeared, fully orchestrated, in 1923. In a certain sense, it belongs more to the period before World War I in its sensibility. Bax came across a poem about Pan leading shepherds in a dance, a late 19th-, early 20th-century invention of a sensuous classicism, to some extent derived from symbolists like Mallarmé. Don't expect anything as languorous as Debussy's Faun. Bax's score opens with bustle, rising to pure animal spirits. The dancers take a breather, in a lovely, lyrical middle, Spring-fresh, a long way from Debussy's steamy summer heat, before they return to the bustle and dance over the hill. Profound, it's not, but it is indeed charming, light music at its best. Bax's orchestration stands out not just for its sound, but for its management of instrumental entrances and exits. Orchestras must find this fun to play.

David Lloyd-Jones and his Scots keep a tight grip on the symphony and serve up plenty of bounce in the tone poem. Again, I like Lloyd-Jones's Bax better than Thomson's, and it's a lot cheaper.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.