The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

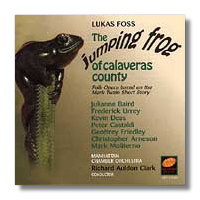

Lukas Foss

The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County

- Julianne Baird (Miss Lulu)

- Frederick Urrey (Smiley)

- Kevin Deas (Stranger)

Manhattan Chamber Orchestra/Richard Auldon Clark

Newport Classics NPD85609 51:04

Summary for the Busy Executive: A gem.

Okay, I might as well get my only beef with this CD off my chest. Its fifty-one minutes runs a little on the light side anyway. However, eleven of those minutes belong to excerpts from the Twain story, read in a hillbilly accent phonier than John Carradine's. Consequently, this CD contains really only forty minutes worth of music. You can't tell me that Foss wrote nothing else Newport Classics could have profitably put on the program. That said, we have a very good performance of what should be an American classic.

Most probably consider Foss a terror of the avant-garde, but he began as one of the brightest lights of neo-classicism, studying with, among others, Hindemith. A composing prodigy, he was likely fully formed in his technique by the age of 18. He fled with his family from Germany during the Thirties and from then until now, he has enjoyed one of the busiest and most versatile musical careers in the United States: pianist, composer, and conductor. For me, his greatest skill lies in his composing. I regard him as a "natural," and the composer he reminds me of most is Mozart. Everything seems to fit together perfectly, and one doesn't catch any extra or superfluous notes. He has gone down so many composing paths with such assurance and individuality that he has very likely written something one would find beautiful or at least interesting. I admit my fondness for his very early and very latest stuff, and I can't point to anything I've heard as weak-minded or ugly.

Whenever he has taken up musical Americana, Foss has almost always Romanticized his materials, very much like someone just off the boat. Unlike Copland's or Bernstein's brand of Romanticism, Foss's ultimately keeps an unassimilated distance, like the cute elderly couple in Casablanca practicing their English. The miners in this brief opera are neither the primitives of Puccini's La Fanciulla nor the mythic heroes of Copland's West. However, they are also not, as in Twain himself, friends and neighbors. They come closest to quaint comic peasants, à la the Bavarian "peasant comedy" of Carl Orff's Der Mond.

On the other hand, very often Europeans tell us something about ourselves we didn't know. Tocqueville's Democracy in America remains the standard work on the subject. Foss's Americana shows us something of the sturdiness of our folk songs and dances, as well as their vitality and suitability for the larger structures of concert music. There's a scene of compositional bravura, almost entirely based on the tune "Betsy from Pike." The changes Foss works on the tune are stunning and surprising at the same time. Who would have thought Sweet Betsy had it in her?

The overture reveals Foss's bifurcated sensibility: it never left Europe. It's pretty and well-made, but neither special nor particularly "American." By the first scene, however, Foss has plunked himself down in the mining camp (at least as a tourist), and the interest - particularly the rhythmic interest - picks up. The music sparkles, every note tells. Foss's speech-setting, artificial as a Fruit Roll-Up, nevertheless comes across as vernacular. It inhabits a twilight of neo-classicism, folk song, and musical comedy. I feel as if I'm watching some gorgeous clockwork mechanism reeling off fiddle tunes, waltzes, even scat. This isn't the West as it was or even as Twain depicts it, but a loving homage to the West by a master musical jeweler.

Foss does all things operatic very well indeed. The Stranger exposes his true colors in a penetrating recitative and rousing aria ("Forty dollars worth of money and a home-cooked meal"). Foss can construct whole scenes - the gamblers' opening of scene two - with elaborate, effortless switches from ensemble to solo and back. The ensembles, particularly the initial praise of the frog-trainer, Smiley, may constitute the most outstanding technical part of the opera. Colloquial phrases and rhythms come together to generate complex rhythmic counterpoint and great drive. Foss writes toe-tapping fugatos, if you can believe it. This is pretty music with no apologies and goes a long way to disprove the incompatibility of beauty and brains.

The opera delights and charms, as a miniature or a pocket watch does, but it also lacks power and sweep. This comes down to genre only in part. Verdi and Vaughan Williams manage to write epic comedies. Foss apparently accepted a libretto which satisfied him, and he realized it beautifully. However, one can't really call this great drama, but a divertissement. One must accept it on those terms.

San Francisco's old After Dinner Opera Company recorded this way back when, with piano accompaniment and delightfully hammy performances. Kevin Deas, also on Chailly's Varèse set, is properly oily as the scamming Stranger. Julianne Baird plays the tender-hearted and slightly mercenary Miss Lulu. Frederick Urrey, as Smiley, puts across naïve pride in his amphibious protégé, Dan'l Webster, rather than the near-pathological compulsion of Twain's gambler, but this is what Foss's libretto (by Jean Karsavina) gives him. The libretto turns a typical Twain idea of human weakness into a celebration of the small town against the wicked city slicker. This recording improves upon the older in every way - voices, full score rather than piano reduction, complete score - and keeps the musical-comedy hamminess. The overture, I believe, appears in commercially-recorded form for the first time, as does "Lulu's Song," originally furnished in the published score as an "addendum." The CD also provides the libretto, although the singers' diction is good enough to understand the action without such help.

Richard Auldon Clark and his Manhattan Chamber Orchestra play lively and tight, and this CD is a worthy addition to their quite interesting discography of American music. The sound is fine.

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz