The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Birtwistle Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

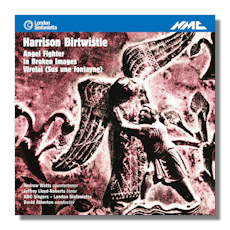

Harrison Birtwistle

Angel Fighter

- Angel Fighter *

- In Broken Images

- Virelai (sus une fontayne)

* Alan Watts (Angel), countertenor

* Jeffrey Lloyd Roberts (Jacob), tenor

* BBC Singers

London Sinfonietta/David Atherton

NMC D211 53:36

Harrison Birtwistle (born 1934) still does not always get full and widespread recognition for the major figure that he is. His scope, concerns and achievements are international; they hold their own with all musical figures of this and the last century. So releases like the present one can do nothing but good in bringing his music to the attention of those both/either previously unaware of its strengths and/or familiar with his output and so keen to keep up to date with his recent enterprises. It's a CD from the admirable NMC with two lengthy pieces (the choral work from 2010, Angel Fighter, at over half an hour and In Broken Images, 2011, at nearly 20 minutes) with the much shorter, earlier (four minutes, 2008), Virelai (sus une fontayne).

They're all live performances – recorded in London, at Cadogan Hall in August 2011 for the BBC, and the Queen Elizabeth Hall in May 2012 and December 2014 respectively – by one of the world's most accomplished and sensitive ensembles performing new music, the London Sinfonietta, under founder and long time (1968-1973, 1989-1991) Director David Atherton.

There is nothing in these performances of advocacy, push, or any expression of the need to apologize for or "wrap" the music in anything other than itself. The projection of voice and instrument is plain, unadorned – hence extremely effective. Avoidance of a "commentary" aspect may also be necessary because of the extent to which these works of Birtwistle's rely on reference.

Angel Fighter looks to both Bach and Stravinsky. Commissioned by the Leipzig Bach Festival for performance in the Thomaskirche, it has a sparseness, an emphasis on woodwind and brass and makes use of a chorus to draw our attention to the action, to the naming of the unnamed… Jacob. The work notably serves as a drama with elements of a judicial trial and has characteristics of a game &nash; as is common in other works by Birtwistle.

The confrontational, the emphasis on stark dialog, the lack of hidden motivation, are also redolent of the Passions of Bach (and his contemporaries). Indeed, it's Stephen Plaice who provided the libretto for this work as well as Birtwistle's chamber opera from 2004, The Io Passion. The language is vernacular and unadorned. But any sense of undue or inappropriate (gratuitously demotic, for instance) rhetoric is entirely absent. The richness of the work also derives from wide variety of textures, palettes, tempi and timbres… from solo declamation to full ensemble. The performers are fully in accord with the idiom, import, intention and necessary conventions to make this a convincing and arresting experience for the listener.

Just as full of tension, substance, meaningful and well-grounded excitement is the purely instrumental In Broken Images. This is similarly scored but has percussion, which Angel Fighter does not. It begins with the fluttering, fragmented snatches of woodwind so characteristic of Birtwistle. The composer's preoccupation with process is to the fore – especially antitheses between haste and rest: the title is from the poem by Robert Graves which applauds the person who is "slow, thinking in broken images" and so arrives at a deeper understanding. Yet this is not music about music. And, significantly, it's played successfully to convey the supremacy of doubt in the Graves poem… if doubt is approached aright!

Nor does the Sinfonietta attempt to purvey it as "experimental" or speculative as such. Sounds, textures, tempi engage (us) because they're changing and moving inexorably towards unity; a unity that's analogous to and derived from Gabrieli's multi-choral Canzone. (Birtwistle's use of) space is as important and telling in this piece as it is in Angel Fighter. There's no doubt that presence at a live performance affords a richer appreciation than can be possible even in as well-recorded a CD as this one. But the listener is nevertheless convinced by the vivacity, tension and sheer energy with which the Sinfonietta approaches every note, phrasing, section and indeed the whole span of this music. It becomes the unity which it was always intended to be. Fragmented, collisional, disjointed both works may appear on the surface. But one's "after-ear" is of tonal worlds as deep and far-reaching as anything more obviously "durchkomponiert".

The astonishingly compact and concise Virelai (sus une fontayne) also alludes to a much earlier composer, Johannes Ciconia (C14th/15th). The virelai which was Birtwistle's starting point is as rhythmically complex as anything from the period. Hence it serves the later composer as a vehicle, a metaphor even, for an exploration of fragmentation, competition, resolution, the unexpected – and the expected, for those with ears to hear.

Ostensibly more conventional in melody and scoring, this short piece might remind one of how lullabies and folk music figure in the work of Peter Maxwell Davies. The springing development of melody is more aggressive – and so more resolvable in Birtwistle's hands – than anything which the medieval idiom could have allowed. As if we simply "know too much". Yet again, the players use imagination and technique to make this an experience in its own right – in ways similar to those of Maxwell Davies, a fellow composer of the Manchester School. There is nothing "arranged" here. Nor derived. Merely a reference. The exuberance, the energy, yet the impression of effortlessness are natural, accomplished and total.

The acoustics of these live recordings add to the excitement and presence required to make the most of the music. The energy and immediacy are captured to good effect. Paul Griffiths writes in the booklet informatively about the music, and how it fits into Birtwistle's world. It contains the complete text of Angel Fighter, information about Birtwistle and the London Sinfonietta. Although Griffiths' essay is printed in white on black… a little hard to read. Even were recordings of any of these three pieces otherwise available (which they are not), this would be a compelling set of performances and one that all lovers of this major figure in contemporary music will not want to miss. Recommended.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey