The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Chausson Reviews

Reger Reviews

Suk Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

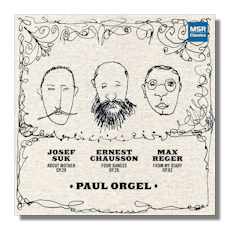

Early 20th-Century Piano Music

- Josef Suk: About Mother, Op. 28 (1907)

- When Mother was a little girl

- Once, in springtime

- How Mother sang at night to her sick child

- Mother's heart

- Remembering

- Ernest Chausson: Four Dances, Op. 26 (1896)

- Dédicace

- Sarabande

- Pavane

- Forlane

- Max Reger: From My Diary, Op. 82, Volume 3 (1910-11)

- Lied

- Albumblatt

- Gavotte

- Romanze

- Melodie

- Humoresque

Paul Orgel, piano

MSR Classics MS1533 60:21

The music on this MSR disc was written in a fifteen-year period, from 1896 to 1911, and can be described as post-Romantic and fairly conservative in its expressive language. Artistically speaking, one can assess that it is all pretty well crafted, perhaps even masterly. Yet, it is rarely encountered in the recital hall and seldom recorded. Why? As I have argued in the past, most recently in my review of the Hindemith piano sonatas earlier this year (MSR Classics MS1507), good piano music is sometimes neglected despite having the necessary ingredients to achieve high art: attractive melodies, fresh harmonies, imaginative structures and very idiomatic piano writing. What these works may lack are those signature elements heard in the music of, say, Debussy, Rachmaninov and Prokofiev: ingenious effects that conjure vivid pictures, or heartrending melodies that seem to cry, or propulsive music that both excites and incites. Indeed, the music on this disc by Josef Suk, Ernest Chausson and Max Reger is pretty straightforward and free of effects, devices and emotional extremes. Yet, much of the time it is bountiful in melody, color and charm – and deeply personal. I won't argue these works are all first-rate masterpieces, but certainly they are worthy of the attention of listeners with an interest in Romantic, post-Romantic and even early 20th-century piano music.

The Suk pieces are brief portraits of his wife, Otylka, who was Antonín Dvořák's daughter and who died very young, not long after the birth of her son. Suk dedicated these pieces to his son, so he would understand something of the mother he couldn't remember and never really knew. They are moving portraits in many ways, but because they are fairly simple and designed to be grasped by a young mind, they are not deep or tragic pieces. "Charming" and "wistful", and maybe "sentimental" are adjectives that come to mind in describing these five short works. The first two pieces are minor gems: When Mother was a little girl features a catchy melody that conveys a playful yet somewhat sad mood; Once, in springtime continues depiction of Otylka as a child and while the general mood is frolicsome and chipper, the music turns a bit wistful near the end. Otylka's failing heartbeat is depicted in the off-kilter ostinato in How Mother sang at night to her sick child, which is a somewhat strange but attractive lullaby. Her heart woes are depicted further in the ensuing Mother's heart, which begins with tensions building that eventually yield to an almost angelic innocence before the tension returns to bring on a crushing ending. Remembering begins brightly as it appears to harken back to pleasant memories of Otylka the child and then Otylka the good wife and mother, but the music darkens as it seemingly struggles to bring her actual presence back to life. A touching piece to top off this fine set! If there is a slight encumbrance here, I would say that it relates to the pieces depending on each other in performance: pianists shouldn't play them separately, as they would a work or two from a Liszt or Brahms set of pieces. Indeed, the whole set should be performed at a single concert.

The four Chausson works are reasonably attractive but, alas, a little understated, perhaps a bit arid too. The Sarabande seems at certain moments to be aiming for something profound but remains elegant and restrained. The ensuing Pavane is a little more extroverted but doesn't break significantly from the subdued manner of the Sarabande. The opening and closing pieces in this set are perhaps the most colorful, with Forlane being the most substantial.

The six pieces comprising Max Reger's From My Diary, Volume 3, are somewhat uneven but mostly strong works that are well worth your attention. In the album notes pianist Paul Orgel mentions the influence of Brahms here, a worthy point to make even though Reger has a recognizable voice of his own. That said, there are certainly short passages where Brahms or Schumann seem to have a ghostly presence. Lied (#1), Romanze (#4) and Melodie (#5) have a haunting melodic character and all three are rather stately and elegant. Brahms is perhaps most noticeable in Lied, but despite whatever influence one discerns, this is a lovely piece still. Humoresque (#6) is light and, yes, humorous, delightfully so, almost seeming to augur the witty and mischievous side of Prokofiev, who was then a student just making a name for himself. The brief Albumblatt (#2) may be a slight misfire here, but the set's longest piece, Gavotte (#3) is one of the finest, even if it is a tad repetitive: it features an infectious busy joy in the outer sections and a delightfully whimsical middle section.

The best sets here then are those by Suk and Reger, though the Chausson has its merits. Paul Orgel points up the plentiful lyricism in these pieces with a splendid legato tone, a sense for proper balances and with tempos that never seem rushed or erratic. The more energetic and spirited music comes across with plenty of energy and detail, and Orgel's technical skills are fully up to the demands of the music here. MSR's sound reproduction is vivid and powerful. If the repertory sounds intriguing to you, this disc should prove rewarding.

Copyright © 2015, Robert Cummings