The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Fauré Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

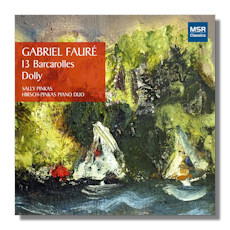

Gabriel Fauré

Piano Music

- 13 Barcarolles

- Dolly for 2 Pianos, Op. 56 *

Sally Pinkas, piano

* Evan Hirsch, piano

MSR Classics MSR1438 72:33

Summary for the Busy Executive: Wonderful barcarolles, so-so Dolly.

For some reason, most classical-music enthusiasts tend to forget about Gabriel Fauré when they think of French music. He usually comes to mind, if at all, for his Requiem. I love Fauré's work, especially his chamber music and songs, but he seems to have become an esoteric taste.

Actually, he seems always to have been such, if you believe the testimony of Aaron Copland, who discusses Fauré's scores almost as if they were cult artifacts. At least Fauré has a cult, rather than has disappeared completely down the oubliette. I've noticed that his fans tend, like me, to adore the music. The music almost eludes you with its subtlety. The composer's harmonic ear leaves me agape. He can reach distant keys and return in two brilliantly chosen chords. He mini-modulates in this way a lot, giving the melody line a kind of shimmer, yet the melody remains paramount – the thread that leads you through a particular score. It's often not functional modulation that establishes a key center, but a coloristic one that destabilizes momentarily the sense of key. When I think of Fauré, I think of the word "fluid." Sometimes, the music breaks your heart.

The barcarolles pose huge challenges to any pianist who wants to take them as a set. First, Fauré himself did not think of them that way, composing them over a period of forty years (1881-1921). Second, most of them share tempo and mood. Shaping them becomes the main concern so that the set itself has a living form. Sally Pinkas does one of the best jobs at this I've ever heard. She invests each barcarolle with its own character, so instead of a wad, we get a distinct shape. She understands this composer like few I've heard.

All the more surprising, then, that the Dolly suite winds up so far off the mark. This two-piano masterpiece owes its inspiration to the daughter of Emma Bardac (at one time Fauré's mistress and Debussy's second wife) – Hélene, nicknamed Dolly. Like Schumann's Kinderszenen and Debussy's Children's Corner, Dolly evokes childhood. In six movements – "Berceuse" (lullaby), "Mi-a-ou," "Le jardin de Dolly" (Dolly's garden), "Kitty-valse," "Tendressse" (tenderness), and "Le pas espagnol" (the Spanish step, in the sense of dance) – the suite alternates between gentle and romping. Some of the titles need explanation. "Mi-a-ou" had nothing to do with cats. It was originally "M. Aoul," toddler Dolly's approximation of her brother Raoul's name. "Kitty-valse," originally "Ketty-valse," referred to the family dog, Ketty. The publisher, for some reason, changed both titles – perhaps a cat-lover.

Although Hirsch and Pinkas generate fine energy in the quick movements, they mess up mainly in the softer ones. They just roughly charge through. "Berceuse," supposedly a lullaby, sounds like a household's mid-morning buzz. "Tendresse" is such only to a dominatrix. Too-quick tempi make up only part of the problem. Instead, I recommend Alfons and Alois Kontarsky on DGG's double-set of Fauré (469268-2) or the Labèque sisters on Philips (4735822), six discs of 2-piano music.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz