The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Kreisler Reviews

Piazzolla Reviews

Q. Porter Reviews

Schulhoff Reviews

Telemann Reviews

A. R Thomas Reviews

Vieuxtemps Reviews

Ysaÿe Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

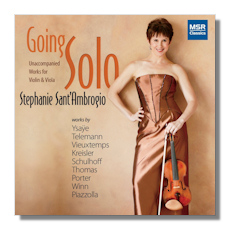

Going Solo

Unaccompanied Works for Violin & Viola

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Fantasia #7 in E Flat Major

- Henri Vieuxtemps: Capriccio, Op. posth. #9

- Eugène Ysaÿe: Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 27/4

- Fritz Kreisler: Recitativo & Scherzo Caprice, Op. 6

- Augusta Read Thomas: Incantation

- James Winn: Pibroch

- Ervín Schulhoff: Sonata for Solo Violin

- Quincy Porter: Suite for Viola Alone

- Ástor Piazzolla: 3 Tango-Etudes

Stephanie Sant'Ambrogio, violin & viola

MSR Classics MS1397 70:20

Summary for the Busy Executive: Satisfying.

I remember very well my first assignment as a formal composition student: write a single-line melody which implies one and only one harmony. It stands as one of the single hardest exercises I've ever done. Sixteenth-century modal counterpoint was tons easier. The homework was harder than coming up with a memorable theme, which in itself is pretty hard. Otherwise, composers would provide one all the time, because very few aspire to forgettable.

J.S. Bach's sonatas, partitas, and suites for violin and for cello represent the gold standard of the genre and provide valuable strategies for the aspiring composer. One could counter that the string instruments are capable of chords, but you can't pull off an extended piece using just chords. Mostly Bach fools the ear by creating in essence a single line that implies more than one voice. Besides, he even wrote a sonata for solo flute, an instrument incapable of chords (overblowing doesn't count, since you have no control over specific pitches). Many of the works on this program owe their inspiration to Bach.

The Telemann fantasia isn't one of them, and it hasn't the richness of Bach. Nevertheless, the compositional strategies resemble one another, particularly for creating counterpoint through shifting the line to a different register. Many of them come from the Italian violin school, especially Antonio Vivaldi, which influenced both Bach and Telemann. The tricks seem more obvious in Telemann. Still, the fantasia comes across as witty and charming.

Notable for Paganini, a school of virtuoso violinist-composers arose in the Nineteenth Century. For my money, the works of the Belgian Henri Vieuxtemps, also a virtuoso violoist, retain the most interest today. The music of the Capriccio belies its title, in that it moves like a grave procession. Vieuxtemps avoids the trap of nattering, an easy pitfall in a solo work, and packs a lot into this three-and-a-half minutes.

Eugène Ysaÿe, another Belgian, studied with Vieuxtemps, among others. According to pop history, he introduced vibrato as an expressive technique in violin playing. I'm not so sure. It may well be that he used vibrato to an unprecedented extent. Inspired by Joseph Szigeti's performance of a Bach solo sonata, Ysaÿe wrote his own set of six, each dedicated to a different violinist: Szigeti, Jacques Thibaud, Georges Enescu, Fritz Kreisler, Mathieu Crickboom, and Manuel Quiroga, respectively. Sant'Ambrogio comments that the composer wrote each sonata in a style characteristic of its dedicatee. The fourth, for Kreisler, has three movements: an Allemande, Sarabande, and Presto. The Sarabande is also a passacaglia, with a theme of only four notes. A bit of a tour de force, it occasionally threatens to fall apart but recovers quickly from whatever lapses. Unusually, it functions as an introduction to the Presto, which handles the passacaglia subject more freely and more brilliantly. The style mixes Baroque and Late-Romantic elements. Beginning with Bach, you may find yourself in the middle of Franck, but you have to be impressed by Ysa¨e's deep mastery of violin writing and technique.

You can say much the same for Fritz Kreisler's own Recitativo and Scherzo Caprice. Kreisler, like most of the violinist-composers, wrote mainly for his own use, including a lot of encore works. He had a brilliant technique, and in that regard, this piece doesn't disappoint. However, every work of his I've heard I'd describe as a well-made bonbon. Instead of Bach, the model here is gypsy music à la hongroise, with the typical slow-fast arrangement of movements. The fiddler first gets your heartstrings to vibrate with the violin's and then dazzles you with a barrage of quick-bursting pyrotechnics.

Until now, I'd never cared much for the music of Augusta Read Thomas. I didn't hate it, but it never really grabbed me. Thomas has garnered much acclaim, and I didn't really understand why. Incantation lets me know the basis for all the fuss. I consider it a masterpiece and probably the most daring work on the program. She wrote it for the cancer-stricken violinist Catherine Tait who later died of the disease. The risk of the work lies in the fact that this consists mostly of a single line of music, with no attempt to put in other voices other than to add an occasional double-stop to imply harmony, and the piece lasts for about five minutes without disintegrating into incoherence. Despite the title, I don't find the work particularly incantatory, since I miss the regularity of rhythm and phrase that I associate with "incantation," but Thomas may well have something else in mind. Nevertheless, the work still wins me over. To me, it meditates on important matters, stringing together about 25 separate phrases. The separations, like a singer taking a breath to consider a new turn of thought, give the piece not only more depth, but a kind of fragility at the same time. Thomas originally wrote the work for the violin, although she approved its adaptation to the viola. I haven't heard the original, but I can imagine it. It seems to me the viola lends a fullness that the violin can't match. I wonder if one could adapt it for a cello and how it would then sound.

In Scotland, "pibroch" denotes a work for the bagpipes of serious character. The United States, however, tends to associate it with bagpipe music played at the gravesite. James Winn wrote his Pibroch in memory of a friend and patron. It opens with a bagpipe drone, but the high pitch of a violin doesn't really put one in mind of bagpipes. I take "pibroch" as a starting point, rather than a depiction, for I doubt any listener would believe Winn ultimately aims at a literalist end. The score falls into three main sections. The first sings a gentle, folk-like melody. If it's not a traditional Scottish tune, it's a marvelous facsimile. The second part pulls the elements of the tune apart, with increasing tension, as if the mourner tries to deal with his grief. After a climax, the work returns to the healing mood of the opening. In many ways, Winn writes the same genre piece as Thomas. Thomas achieves greater emotional complexity, but Winn writes the more song-like work.

I was about to call Czech composer Ervín Schulhoff a recent discovery but then remembered that I've known his music for about forty years, which gives you some idea of my age. A prodigiously talented composer, Schulhoff, although an early user of jazz in his music (he had a huge private collection of American jazz records), didn't innovate or have an immediately-identifiable voice, like Bohuslav Martinů. He tended to dip into the various musical currents of the Twenties and Thirties and create his own wonderful examples. His Sonata for Solo Violin I consider one of the best instances of a difficult genre. In four movements, it speaks in at least two voices. The three folky movements seem to take off from Igor Stravinsky, particularly L'Histoire du Soldat, while the slow movement echoes Alban Berg. Each movement, however, either gets the feet moving or the soul to yearn – my favorite piece on the CD.

I doubt many will recognize the name Quincy Porter. A scion of Yale (he not only attended, his father was on the faculty) and later a teacher there, he studied privately for a time with Ernest Bloch and Vincent d'Indy and worked for Bloch at the Cleveland Institute of Music. He had a notable career as an academic, also hitting Vassar and the New England Conservatory of Music (as its director). Chamber musicians probably know Porter best, and he has a fine cycle of string quartets. His most effective works (I recommend New England Episodes for orchestra) have a certain nobility. When he misses, however, he sinks into the polite. For me, his Suite for Viola Alone falls into the genteel mire. Nothing about it grabs me. One man's meat, etc.

My knowledge of tango comes almost entirely from popular movies and the number "Jalousie." Although I have heard a lot of tango nuevo, the genre pioneered by the Argentinean composer Ástor Piazzolla, I have very little idea what it is, other than more various than "Jalousie." Consequently, a good deal of Piazzolla's 3 Tango Studies has flown over my head. Fortunately, you don't need to know tango to like these three miniatures. Piazzolla studied with both Alberto Ginastera and Nadia Boulanger and led a tango band. In the early days, he played dives and got into bar fights. He made it his artistic mission to unite Argentinean pop with expansive classical procedures. Each of these little studies follows normal song and dance structures within a harmonic and melodic framework more wide-ranging than usual in pop. The first reminds me of a soulful guitar in the night. The second two I more easily accept as tangos. They pop rhythmically. Piazzolla amazes me in that he doesn't seem to acknowledge any problem at all in writing a piece for a solo string instrument. The studies move "naturally."

I know little about violin-playing. Indeed, I can seldom tell, from a technical viewpoint, one violinist from another. Good intonation and good rhythm seem to satisfy me. Rather, a player's point of view identifies him or her to me. I can distinguish Heifetz from Hilary Hahn. Stephanie Sant'Ambrogio reveals herself as a fine musician. Beyond the basics of rhythm and tuning, her main virtues here are a deep understanding of the structure of each piece, the ability to communicate that structure to the listener, contrapuntal clarity when called for, and a chameleonic faculty for disappearing into each piece. It's an accomplishment to take on so well the wide range among Thomas's Incantation, Ysaÿe's and Schulhoff's sonatas, and Piazzolla's tangos. Altogether a superior program and performance.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz