The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hindemith Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

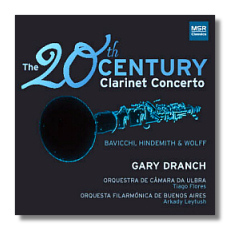

The 20th-Century Clarinet Concerto

- Daniel Wolff: Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra (1999)

- John Bavicchi: Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra, Op. 11 (1954)

- Paul Hindemith: Concerto for Clarinet in A Major (1947)*

Gary Dranch, clarinet

Orquestra de Cámara da Ulbra/Tiago Flores

* Orquesta Filarmónica de Buenos Aires/Arkady Leytush

MSR Classics MS1180 71:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: One game try, one lame try, and one masterpiece.

Three modern clarinet concertos, one of them less than ten years old, none of them widely recorded, and all of them fairly conservative.

The clarinetist Gary Dranch has professional ties to South America. In the late Nineties, he asked Brazilian composer and pop maven Daniel Wolff for a "Brazilian" concerto. He got his wish only in the finale. The music goes along pleasantly enough, although you may find yourself yawning in the first two movements. There's nothing particularly Brazilian in either, and the inclusion might have helped. They natter and ramble. They even stop and start again (the first movement at least three times), which indicates that there's no real argument here, just one thing after the next, even though you can easily distinguish the "big bones" like exposition, first and second subject groups, development, and recap. However, Wolff's sense of harmonic function comes across as weak or non-existent. A change of harmonic center tends to occur mid-phrase, rather than at any structural lynchpin. Even so, he modulates only to quickly return to home tonality, like a child in a department store who takes a few steps from his mother and then runs back to grab her hand. The third movement arrives as welcome relief – a lively, hip-swinging samba. For the first time, Wolff has his act together. The main idea makes an impact, rather than runs out of gas. The movement hangs together easily and naturally without losing its train of thought.

Much better is the concerto by John Bavicchi, influenced by, I think, Baroque practice and by Hindemith. A graduate of the New England Conservatory, Bavicchi has taught composition and conducting for many years at the Berklee College of Music. The first movement unwinds as a slow procession, much like the opening to Nobilissima Visione. The second movement, a spectral scherzo, moves in mixed meters, mainly 5/8 and 6/8. The ideas in both have a good deal of interest, and some of them even surprise. One notes here and there little Hindemithian riffs in the accompaniment. The last movement, on the other hand, seems to me a bit of a mess, Bavicchi's control over the rhetorical process a lot looser, although the basic language in itself holds one's attention. It's also the longest movement. Nothing falls apart to the extent of the first two movements of the Wolff concerto, but the argument as a whole fails to make an impact. Furthermore, there's no "breakout" moment. Nothing that astonishes you and compels you to listen. I guess Bavicchi would help himself by indulging in a little vulgarity once in a while. Nevertheless, I was happy to make the composer's acquaintance.

However, I couldn't wait to get to the "big work" on the program: the Hindemith clarinet concerto. I have never quite understood why the star soloists – Stoltzman, Shifrin, Meyer – haven't trampled one another in a rush to record it. Then again, I say the same thing about Hindemith's violin concerto and cello concerto. Hindemith wrote his clarinet concerto in the Forties, at the height of his powers, or at least in his most sonically-beautiful period, among other works like the 6 Chansons, Requiem, Symphonic Metamorphoses, Nobilissima Visione, and the violin and cello concertos. In four movements, the concerto gives the clarinet one of its noblest roles in the literature. The first movement, based on only two themes, is a cornucopia of contrapuntal virtuosity, much of it in fugue. The drama of the movement consists in the composer's teasing out the resemblances between two superficially-different ideas. There's a sense of power and ease in all this, and it's gorgeous, besides. The second movement, a short scherzo, whirls and spins about like a spring-toy out of control, but of course Hindemith takes you only to the tipping point of chaos before lightly reining everything back in. The movement ends in the middle of nowhere, but for all that, it satisfies, rather than perplexes, and reminds you that "scherzo" literally means "joke."

The slow movement follows much the same strategy of the first: two themes in contrapuntal treatment, sometimes simultaneously. However, the counterpoint doesn't give the movement its raison d'être. Instead, Hindemith celebrates the clarinet as singer, spinning out a silvery line. Composers normally write this way for oboe or cello, and indeed the "feel" of this slow movement reminds me very much of the slow movement from Hindemith's cello concerto. The finale, marked "merry" (heiter, in German) starts out in a way that almost tricks you into thinking it free-wheeling. It's high-spirited and powerful by turns. In his liner notes, Dranch describes the concerto as "aloof," but I think that misses the mark. Hindemith tends to exercise more-than-normal control over his materials (knowing when to let up and how much marks him as a master), but that usually means that what he controls is very potent indeed, especially at the magnificent gathering points and climaxes of the movement. The concerto begins and ends in blazes of glory.

I wish the performances were better. Dranch is fine, but in the first two concerti, conducted by Tiago Flores, his backup seems asleep. The string tone is dull, the rhythm slack. It's the kind of performance that new-music lovers used to suffer through in the bad old days, until musicians finally became comfortable with modern and contemporary idioms. This does the Bavicchi no good at all and sinks the Wolff. The orchestra in the Hindemith is leagues better, but at several points, one hears this orchestral section or the next dragging almost to the point of falling apart. Some other section then steps in to keep time. First, the strings muddy their part, while the brass and wind become the metronome. Another time, it's the winds who have to turn to the strings, and so on. I can't recommend you getting this CD for the Wolff at all, and the Bavicchi suffers very largely from performance vagaries. I find the Hindemith, though good here, gets a better shake in the EMI performance led by the composer, despite its age (EMI 77344).

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz