The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Allegri Reviews

Byrd Reviews

Palestrina Reviews

Tallis Reviews

Victoria Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

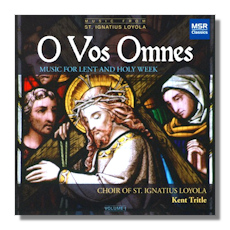

Choir of St. Ignatius Loyola

O Vos Omnes

Music for Lent and Holy Week

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Sicut servus

- Anonymous:

- Pange lingua

- O homo considera/O homo de pulvere/Filiae Jerusalem

- William Byrd: Ave verum corpus

- Tomás Luis de Victoria: O vos omnes

- Gregorio Allegri: Miserere mei, Deus

- Thomas Tallis:

- The Lamentations of Jeremiah, I & II

- O sacrum convivium

Choir of St. Ignatius Loyola/Kent Tritle

MSR Classics MS1138 50:43

Summary for the Busy Executive: As beautiful as stone.

To an ensemble singer, the choral music of the Renaissance occupies the same place as the quartets of Haydn and Beethoven to the string player: the core of the repertoire. For me, the best of that music lies in the great masses: by Ockeghem, Obrecht, Josquin, Taverner, Palestrina, Byrd, and many, many others. However, one encounters many hitches to performance, rooted mainly in the fact that we have very few clues as to the emotional implications of modal, as opposed harmonic music. At any rate, we don't feel them, as we feel the difference between major and minor, although scholars intellectually understand their conventional meanings. Furthermore, most composers of the era used no expressive markings – nothing to give you tempo or dynamic or sometimes even chromatic alteration of pitch. I've heard radically different realizations of the same scores. Then there's the question of proper performance style. We can never know exactly what the contemporary audiences heard. We can know the size of forces from pay records. We can make certain informed guesses, but questions remain. For example, did these pieces have instrumental accompaniment or did composers leave singers on their own? Was the arrangement even consistent from one occasion to the next? Which instruments?

It used to be that, absent any indication from the composer, one always performed (assuming a competent choir) Renaissance choral music a cappella. A chorister myself, I grew up hearing and performing it this way. And it trained you, honed your hearing, made you more aware of your part in the texture. It makes choirs better, even in later repertoire. A steady diet of Beethoven, Verdi, and Bruckner depletes you. Josquin and Byrd replenish. It's like returning to the gym after playing the Big Game. The emotional distance between us and the music actually, I think, frees up performers. You have scrupulous scholarly accounts as well as wild, off-the-wall ones. I have no skin invested either way in the HIP controversy. I've heard great performances that took antipodal approaches. The only thing that bothers me is listening to one side or the other claim for itself the only true fidelity. HIP, after all, is a modern construction. No Renaissance choirmaster thought of his practice as "historically informed," in our sense. He didn't have to construct and justify a rationale. He simply performed music in the way he thought it should go, the way any "truly musical person" would have done it. On the other hand, those who defend an essentially Romantic approach by claiming fidelity to the spirit or Naturalness are blind to their own stylistic origins. Most art music, unfortunately, isn't natural. You don't find a Haydn sonata washed up like a shell on the beach. Art is created by, among other things, sets of conventions and decisions.

Most of the "hits" of this repertoire tend to come later in the period, closer to us, from composers like Byrd, Gibbons, Tallis, Palestrina, Victoria, and Lassus. Ockeghem doesn't have a hit, nor do Josquin and Dufay. Consequently, that's what you usually hear in concert, and Tritle builds this kind of program, with two exceptions: the plainchant "Pange lingua" and the organum triplum "O homo considera/O homo de pulvere/Filiae Jerusalem," both from the medieval period. In "O homo considera," three texts are sung simultaneously, one text to a part. I'm not sure as to what lay behind this practice, but it began with the so-called School of Notre Dame, its great practitioner Perotin. There are many examples of the genre. Remnants of it survived in the Renaissance, in motets where one text commented on another, as in Josquin's chanson "Nymphes des bois/Requiem aeternam," his lament on the death of Ockeghem.

I first heard Kent Tritle and his Ignatians on a stunning CD of Ginastera and Schnittke. They made it obvious that their technique was up to anything a composer might put their way. Here, they pass the cruel test of a pure, blended unison in the plainchant. Their sense of pitch throughout the program becomes an exciting element in itself. The intricate contrapuntal textures (in all but the triplum) are clear as water. One easily falls in love with this disc. I wasn't wild about the Allegri Miserere, but I never am. This was the piece that the boy Mozart wrote out from memory, because the Vatican wouldn't allow performances of it outside its walls. Why they took such pains over such a mediocre work puzzles me. Its only "hook," really, is a high C for some lucky soprano or sopranos, an athletic feat more than music.

However, despite the disc's many pleasures (including a wonderful "Sicut cervus"), I'm not fully on board. Tritle's readings could use a bit of warmth or drama. The singing is beautiful, but remote. It emphasizes the emotional and temporal distance between the composers and us. It also de-emphasizes the differences among composers. I'd contend that Palestrina, Tallis, Byrd, and Victoria write music of quite individual character. Palestrina and Tallis, at the least, are more "even-tempered," while Byrd and Victoria are drawn to drama, Victoria more overtly than Byrd. Nevertheless, many prefer Tritle's approach, which I should emphasize, yields technically superb results. The sound comes from a stone cathedral and fills the vaults.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.