The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

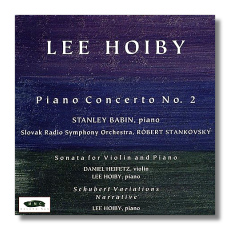

Lee Hoiby

Orchestral Works

- Piano Concerto #2 1

- Schubert Variations 2

- Narrative 2

- Sonata for Violin & Piano 3

1 Stanley Babin, piano

2,3 Lee Hoiby, piano

3 Daniel Heifetz, violin

Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/Robert Stankovsky

MMC Recordings MMC2038 DDD 70:53

Lee Hoiby, pianist and composer, studied piano with Egon Petri and composition and orchestration with Menotti (who hasn't taken all that many pupils). Hoiby came to attention in the Fifties and Sixties, mainly through his stage works, but it was a bad time for a composer with a tonal idiom. The post-Webernian serialists had ascended, and many of them were busy excommunicating non-believers from serious consideration, as if a person who liked Webern and Boulez couldn't also like Rachmaninoff and Barber. Those days have passed (unlamented by me). It's a good time to reassess the neoclassicists and the post-Romantics – people like Piston, Diamond, Creston, Hoiby, Floyd, Hanson, Dello Joio, Harrison, late Thomson, Menotti, and Pasatieri. To some extent, this has happened with the symphonists and with those composers based in New York. Hoiby is neither. Most of his major work remains unrecorded. Therefore, this disk is particularly welcome.

When people ask composers the standard question where they get their ideas, I'm convinced they don't expect an answer, so much as wish to express their admiration for the quality of the composer's ideas. In Hoiby's case, it makes particular sense to ask this question: not only is Hoiby's manipulation superb, but the ideas or themes themselves are of high quality. For example, Grieg thinks splendid thoughts but has trouble extending them, as in the Piano Concerto. Beethoven masters the art of extension and development, but (as has often been pointed out) the material developed is simple to the point of triviality, as in the astonishing slow movement to the 7th Symphony. The point is that Hoiby knows what to do with the great thoughts he has. I don't hesitate to call the Piano Concerto #2 one of the finest of the century. Nothing is routine, nothing is deadwood, and – surprise – nothing is unintelligible. By rights, this should become one of the most popular concerti in the literature.

The concerto very curiously combines two opposing tendencies in the piano writing: a Scarlattian fleetness and a sonorous, almost Rachmaninoff fullness. The general idiom I would call American neo-classic, although Hoiby has been compared to Barber and Menotti – supposed neo-Romantics. To me, the label fits someone like Hanson better, for both Barber and Menotti probably owe more to Stravinsky than to any other composer. One might call Barber, Menotti, and Hoiby neo-classicists who still can write lyrical tunes. A virtuoso pianist himself, Hoiby certainly knows how to write for the instrument, and his orchestration (here I find him closest to Menotti) is nothing to sneeze at either. In the short introduction, wisps of themes (which we will hear throughout the movement) skirl about and coalesce quickly (something like the liquid-metal assassin in Terminator 2) into the first subject group – a fanfare taking off into Scarlatti-like passagework. This gets the blood going – the general function of fast sections in this concerto. The lyrical second subject will melt you. It shares the yearning of Rachmaninoff's 18th Paganini variation, and yet it seems to come from the first subject group. Both of these subjects get worked over in fantastic, constantly surprising variation.

Mark Shulgasser's liner notes point out that the emotional core of Hoiby's work lies in the slow movements and in lyrical second subjects. I think this a bit unfair about Hoiby's music in general, but it's true enough of this concerto. One critic labeled the second movement "Hollywoodish." Shulgasser rightly counters that really good Hollywood film music has nothing to be ashamed of. I, however, don't really find the adjective all that apt. Certainly, Hoiby can sing, and sing beautifully, but it's something unique to him, and he never goes the sure-fire route to the listener's wow or sigh. Again, the composer who comes most to mind is Rachmaninoff, but the idioms differ. Rachmaninoff seems to give Chopin a Slavic ginger. Hoiby's lyricism isn't so retrograde or so self-consciously nostalgic. To me, it's the art-music equivalent of "Shenandoah." The Rachmaninoff echoes may come down to a similarity in how both composers build the arch of a phrase and in the piano sound, rather than in specific borrowing. I should mention here that soloist Stanley Babin makes his piano sing like Janet Baker. But if it were as easy and natural as he makes it sound, anyone could do it.

The third movement begins in a shower of notes. It's a rondo with a breathtakingly imaginative turn in each episode, including hints of South American samba toward the end. Pianist Babin makes sparks here.

The Slovak Radio Symphony under Stankowsky accompany beautifully, for the most part. The recording errs, I think, in placing the piano too far forward, so that it's hard to catch the orchestral byplay. In the third movement, the playing becomes choppy and ragged, as if the orchestra is trying to keep up with the soloist, but there are no major mishaps. The sound, if not up to, say, Decca's techno-wonderful, is still pretty good.

Oddly enough, most composers performing their own works tend to a grittier conception of the music than do secondary executants. Strauss, for example, insisted on a "rougher" sound from the orchestra than the usual smooth, rich, and suave. Rachmaninoff almost tromps through many of his piano works. I found it interesting to compare Hoiby with Babin in this regard, particularly in the performance of lyrical sections. Babin definitely comes out "sweeter." With Hoiby, you get the structural steel beneath the tune. This comes out in the Schubert Variations and in Narrative for solo piano.

Variations come in two main flavors: the 18th-century aria variée, which proceeds by increasingly complex ornamentation, and the "architectural" variation, which essentially takes apart the elements of the theme and varies each one. Composers like Beethoven and especially Brahms and Elgar add a "symphonic" element as well, where the discrete variations somehow coalesce into larger units. Hoiby's Schubert Variations tries to combine the "architectural" and symphonic approaches. He takes a sad little Ländler further and further afield (it almost seems as if he leaps from tangent to tangent), intending to lead us back to the main theme at the end, much as Brahms does in the Haydn Variations. The variations themselves are spiffy, but the return to the theme seems too abrupt to me.

Narrative strikes me as the most complex work on the disc, not in idiom (no harder than middle-period Barber), but in its structure. I had to listen a few times before I began to realize what was going on. You don't have to analyze the piece (although I like to) in order to have a fine, exciting time with it, however. As the title implies, you can get caught up in the flow, as you can hang to the thread of a well-told tale. To me, the piece cries out to be orchestrated, and I'm not taking a swipe at Hoiby's super performance when I say this. However, the highly contrapuntal nature of the music, with a few thematic cells jumping from voice to voice, seems to me to argue for the "color separation" different instruments would provide.

Hoiby's handsome Violin Sonata allows the violinist and pianist mostly to get sociable, rather than plumb psychological depths. It lies closer to something like the Cowell and Piston sonatas, rather than to Brahms, Bloch, or Bartók. The themes are gorgeous, although one says of the sonata, "How beautiful," rather than "How uplifting and profound." I must admit that at times I get tired of composers preaching at me. Chesterton once said, "Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly…. It is easy to be heavy: hard to be light. Satan fell by force of gravity." Hoiby's sonata almost levitates because he takes the harder artistic path of levity. By the time the genuinely deep slow movement arrives, the listener is light enough to receive it. I'm no judge of violinists (I don't even like the sound of the violin per se), but to me Daniel Heifetz gives the sonata the youthful ardency it requires. In fact, both performers take great delight in the harmonic and melodic twists of the work. The final movement to me evokes the barn-dance fiddle so well that it was difficult for me to keep still. A splendid work.

Recommended.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz