The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Martin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

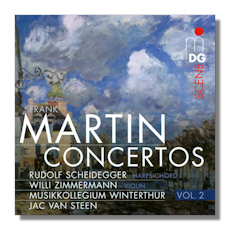

Frank Martin

Concertos, Volume 2

- Polyptyque for Violin Solo & 2 Little Strings Orchestras

- Passacaille for String Orchestra

- Harpsichord Concerto

Rudolf Scheidegger, harpsichord

Willi Zimmermann, violin

Musikkollegium Winterthur/Jac van Steen

Dabringhaus & Grimm MDG9011539-6 DDD 60:43 Hybrid Multichannel SACD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Bach and the Spanish earth.

Frank Martin (pronounced, in the French way, Frahnk Mar-TAN) has a complex artistic history. Born in Geneva, Martin (1890-1974) grew up in, at the time, a German musical culture. It took conductor Ernest Ansermet to introduce and establish French composers in Swiss concert repertory. Martin's earliest music reflected German taste, especially a life-long inspiration of J. S. Bach. He eventually became one of the great composers of sacred music in the Modern era. By the Twenties, however, he had accommodated French Impressionist harmony into his language without ever quite becoming an Impressionist. Martin had no formal training as a composer. He worked on his own, and he kept his independence throughout his life. For example, he became interested in certain ideas of Arnold Schoenberg but never went over to atonality. He remained steadfast in his belief in harmony as the strongest musical element. Over the years, his idiom changed several times, which makes him hard to classify, something that may account for his relative neglect among musicologists. Nevertheless, great musicians continue to program his music. I would compare him in this respect to Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů.

Polyptyque (1973) sprung from a commission from violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who wanted a concerto for violin and string orchestra. The examples of Bach in that genre intimidated Martin to the point that instead of a concerto, he wrote a suite of six "pictures." However, he didn't make things easy on himself, scoring the work for two string orchestras and solo violin. Inspired by a series of Renaissance panels, Polyptyque depicts the Passion story from Jesus's entry into Jerusalem through his resurrection. The forces divide, much as Bach's Passions do, between the turba (crowd) or congregation and the reflections of the individual soul. Martin has beautifully realized the possibilities of his instrumentation, in ways that dramatize the program. The strings engage in call and response as well as interpenetrate with complex counterpoint. "The Upper Room," my favorite movement and the longest, begins with an extended violin solo, unsupported by the orchestra, depicting Jesus's farewell to his disciples. "Judas" moves with agitation and anguish. "Glorification" contains the most consonant harmonies, but the dissonance that remains lingers as stabs of remorse. However, you needn't buy into Martin's program. The work strongly stands on its own as an abstract musical structure.

The 1944 Passacaille (passacaglia), originally for organ, appears here in Martin's 1952 reworking for strings. In the archetypal passacaglia, the composer creates a bass line that repeats over and over, above which he sets varied material. You can think of Pachelbel's well-known canon as a passacaglia. Although Bach's great example in c-minor almost certainly lurks in the background, Martin's maverick instincts lead him to something slightly different. The bass line doesn't stay the same. From the middle of the score on, Martin inserts extra measures. Further, a structural feature of the bass line allows Martin, from the fourteenth variation on, to modulate up a half step, until he returns to the original pitch. This results in a gradual "brightening" as well as a crescendo over a very long span. Martin has found a way to create a dynamic form from a static one.

Martin's concertos (at least six) have enjoyed high critical regard. Critics point out not only his idiomatic writing, but also his acute "feel" for the instrument in question. The 1952 Harpsichord Concerto, in two movements, ranks, with the Falla Harpsichord Concerto and the Poulenc Concert champêtre, as one of the finest modern examples for the instrument. Martin had no specific programmatic intent, although he did mention that the opening theme was inspired by watching the waves of the North Sea. Nevertheless, I've always been struck by the Spanish "vibe" of the score – moody and dramatic and dominated by Iberian rhythms. Indeed, I have discovered that the music was used for a ballet on Lorca's House of Bernarda Alba, to give you some idea of the work's mood. The spiky first movement is a modified sonata form: exposition, development, but no real recapitulation. The second movement, much looser but not really sectional or incoherent, moves between cancín and danza. Martin may have marked the latter "Tempo di valse," but it's nothing you'd hear in Paris, St. Petersburg, or Vienna. It relates more to the Spanish jota. The work broods and stings.

The performances, while not earth-shaking, are fine. Martin doesn't allow performers to space out. I do prefer the composer's own conducting of the harpsichord concerto with Christiane Jaccottet at the keyboard – less pokey and more dramatic, but I have no idea whether the CD (Jecklin Disco JD 529-2) is still available.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz