The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Decca Classic Recitals

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau: Haydn & Mozart Discoveries

- Franz Joseph Haydn:

- Un cor sì tenero, H 24b:11

- La vera costanza, H 28:8: Excerpt(s)

- Acide, H 28: Tergi i vezzosi

- Dice, benissimo, H 24b no 5

- Wolfgang Mozart:

- Warnung, K 433 (416c)

- Ich möchte wohl der Kaiser sein, K 539

- La finta giardiniera, K 196: Con un vezzo all'italiana

- Mentre ti lascio, o figlia, K 513

- Così dunque tradisci…Aspri rimorsi atroci, K 432 (421a)

- Un bacio di mano, K 541

- Le nozze di Figaro, K 492: Hai gia vinta la causa…Vedrò mentr'iosospiro

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone

Vienna Haydn Orchestra/Reinhard Peters

Decca 4757169 ADD 42:56

Fernando Corena: Operatic Arias For Bass

- Gioachino Rossini:

- La Cenerentola: "Miei rampolli femminini" & "Sia qualunque delle figlie"

- L'italiana in Algeri – "Ho un gran peso sulla testa

- Domenico Cimarosa: Il matrimonio segreto: Udite, tutti, udite

- Jules Massenet: Grisélidis: Jusqu' ici sans dangers

- Ambroise Thomas: Le caïd: Enfant chéri…Le tambour-major tout galonné "Drum Major's Aria"

- Camille Saint-Saëns: Le pas d'armes du Roi Jean

- Charles Gounod: Philémon et Baucis: Au bruit des lourds marteaux

- Jacques Offenbach: La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein: A cheval sur la discipline

Fernando Corena, bass

Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino/Gianandrea Gavazzeni

L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/James Walker

Decca 4757170 ADD mono 39:15

Renata Tebaldi

- Giuseppe Verdi:

- Don Carlos: Tu, che la vanitá conoscesti del mondo

- Un ballo in maschera: "Ecco l'orrido campo…Ma dall' arido stelo divulsa" & "Morrò, ma prima in grazia"

- Giovanna d'Arco: Oh, ben s'addice questo torbido cielo

- Giacomo Puccini:

- Turandot "In questa reggia"

- La Rondine: Ch'il bel sogno di Doretta

- Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana: Voi lo sapete, o Mamma

- Francesco Cilèa: L'Arlesiana: Esser madre è un inferno

- Amilcare Ponchielli: La Gioconda: Suicidio!

Renata Tebaldi, soprano

New Philharmonia Orchestra/Oliviero di Fabritiis

Decca 4757166 ADD 52:23

Pilar Lorengar: Prima Donna In Vienna

- Wolfgang Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro, K 492: E Susanna non vien…Dove sono

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Fidelio, Op. 72: O, wär ich schon mit dir vereint

- Carl Maria von Weber: Der Freischütz, J 277: Wie nahte mir der Schlummer

- Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser: Dich, teure Halle

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Die tote Stadt, Op. 12: Glück, das mir verblieb "Mariettalied"

- Richard Strauss: Arabella, Op. 79: Aber der Richtige

- Johann Strauss Jr.. Der Zigeunerbaron: O habet Acht

- Carl Zeller: Der Vogelhändler: Schenkt man sich Rosen

- Franz Lehár:

- Eva: Wär es auch nichts als ein Augenblick

- Zigeunerliebe: Hör' ich Cymbalklänge

- Imre Kálmán: Die Csárdásfürstin: O jag' dem Glück nicht nach

Pilar Lorengar, soprano

Arleen Auger, soprano

Vienna Opera Orchestra/Walter Weller

Decca 4757165 ADD 52:58

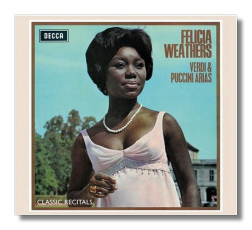

Felicia Weathers

- Giuseppe Verdi:

- Don Carlos – "Tu, che la vanitá conoscesti del mondo" & "Non pianger, mia compagna"

- Otello: Piangea cantando…Ave Maria

- Giacomo Puccini:

- Manon Lescaut: In quelle trine morbide & "Sola, perduta, abbandonata"

- Turandot: Tu, che di gel sei cinta

- Madama Butterfly: Un bel dì vedremo

- Suor Angelica: Senza mamma, o bimbo, tu sei morto

- Gianni Schicchi: O mio babbino caro

Felicia Weathers, soprano

Vienna Opera Orchestra/Argeo Quadri

Decca 4757167 ADD 50:59

This is the latest set of releases in Decca's "Classic Recitals" series. All five are newly transferred to CD, and feature important singers at the peak of their powers, or close to it. In an era in which reissues tend to be the same thing over and over again, just in different packages, Decca is to be thanked for going back into the archives and pulling out one plum after another, and for doing a nice job with the digital remasterings. Still, a little more TLC would have been nice. Decca has slavishly stuck with the material that was on the original LPs, so all of the releases in this series are short by CD standards. Worse, the original record covers simply have been scanned and reduced for these "digipak" reissues, so the liner notes on the back cover are difficult if not impossible to read. (We are directed to Decca's website to view them, but that's hardly an answer.) I'm all for nostalgia, but not if I'm going to go blind in the process! And really, shouldn't we be told more about these singers than what they were doing up until the time they recorded these albums?

In the 1970s, it looked as though Joseph Haydn's operas might be making a comeback, thanks to Antal Doráti's series of complete recordings for Philips. Alas, it did not come to be, but Doráti's recordings have been reissued on CD, as has a disc of Haydn and Mozart "discoveries" sung by the versatile Dietrich Fischer Dieskau. Il disertore actually is the work of Bianchi, and La scuola de' gelosi was written by Salieri; Haydn's arias were inserted into later performances of these operas, as often was done at the time. In contrast, La vera costanza is all Haydn's (and it is one of his most famous operas), as is Acide e Galatea, which is much less familiar. Haydn's writing is as mellifluous as one would expect it to be, and the arias run the gamut from tenderness to broad humor. Nevertheless, this is a side of Haydn we infrequently see, and it is welcome.

Two of the Mozart selections also are "insertion arias" for operas by Paisiello and Anfossi. (The glorious Mentre ti lascio, written for the former's La disfatta di Dario, was hardly a "discovery," however – even in 1969, when this disc was recorded.) La finta giardiniera, when it is performed at all, usually is performed in Italian, but here we are given a buffo aria in an alternative German version. (In it, the character Nardo advises how woman in France, Italy, Germany, and England are to be wooed in their mother tongue, so this is a polyglot aria!) "Hai già vinta la causa… Vedrò mentr'io sospiro" is from Le Nozze di Figaro, and is a "discovery" only because it is taken from a 1789 revival of the opera, not from the original score with which we are familiar. The other two selections are free-standing arias composed for various occasions. Even in these less familiar works, Mozart's genial and penetrating genius comes shining through.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau's voice is so characteristic that it becomes hard to separate the singer from the song. In 1969 he sounded hale and hearty and at the top of his game. Whether he is singing in Italian, German, French, or English, he communicates the meaning of every word, and he finds a different vocal personality for every selection. This is a nice addition to the reissue discography of a very well recorded singer. Peters and the Vienna Haydn Orchestra play stylishly, albeit on modern instruments, and the engineering still sounds fresh.

In the 1950s and 60s, Fernando Corena (Swiss by birth, Italian by name, but of Turkish heritage), was one of the most popular exponents of comic bass roles in the Italian repertoire. Dulcamara (L'elisir d'amore), Fra Melitone (La forza del destino), and the Sacristan (Tosca) were roles he must have sung hundreds of times. Rossini's buffo characters were the centerpiece of his repertoire – not just Don Bartolo from Il barbiere di Siviglia (not represented here), but the other pompous fools whom Rossini depicted so well in music. Both Rossini and Donizetti wrote demanding "patter" arias for basses – the goal was to squeeze as many words as possible into a short space! – and Corena was the master of them. "Sia qualunque delle figlie" from La Cenerentola is one of the most demanding of all, and on this CD, Corena tears through it without breaking a sweat, and with no compromise in tonal quality.

Corena's contributions to the French repertoire are not as frequently remembered today, but the second "side" of this CD puts matters right. There's more variety here than on the Italian "side," as Corena portrays military personages, Vulcan, and even the devil himself. (It seems that even Satan has marital problems!) Given his Swiss upbringing, it is no surprise that Corena's French diction is excellent, and he lightens the timbre of his voice here to be consistent with the style of the music. The only disappointment, and it is a minor one, is in General Boum's aria from La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein, where Corena ducks Offenbach's high notes and consistently misreads the text. (It's "tara papa poum," not "tara para poum." Okay, it's not the end of the world!)

Gavazzeni and the Florentine accompany Corena in the Italian selections, and Walker and the Swiss in the French. The monaural recording (September and October 1956) still packs punch.

In the1950s, Renata Tebaldi and Maria Callas – or more accurately, their fans – were at loggerheads with each other. Today, it all seems a little silly: Callas was Callas, and Tebaldi was Tebaldi. Just because you like chocolate ice cream doesn't mean you can't like vanilla. By 1964, when this Tebaldi recital was recorded, Callas was close to being out of the running. Tebaldi, though she was approaching the end of her career, still had a lot to give, as this program proves. Most interesting is her "In questa reggia" from Turandot. Praised for her interpretation of the opera's other soprano role, Tebaldi gives us a taste of what she might have been like as the icy Chinese princess. She starts the aria as if in a dream state, and then gradually adds color and expression to her voice as she becomes aware of the latest challenge to her virginity. It's a powerful reading. Equally gorgeous is the "Sogno di Doretta" from La rondine – another role which Tebaldi did not record. Again, this is an interpretation based on intimacy and on the dawning of personal consciousness.

By 1964, Tebaldi's voice had become markedly darker, and her high notes were no longer as beautiful as they once were. (Some might actually find them unpleasant.) Her characterizations had deepened, however, and her voice had taken on a regal quality which was especially appropriate for the Princess Turandot and for Elisabetta from Don Carlos. Her maternal qualities come to the fore in "Morrò, ma prima in grazia" (Un ballo in maschera) and in "Esser madre è un inferno" (Cilèa's L'Arlesiana). Giovanna d'Arco was a watershed for Tebaldi near the start of her career. Here, she no longer sounds like the Maid of Orleans, but you can't deny her involvement. Only the shifting moods of "Ecco l'orrido campo… Ma dall'arido stelo divulsa" from Un ballo in maschera evade her. Nevertheless, Tebaldi's singing is incredible throughout. She and the orchestra have a tendency to go their separate ways, however. The conducting of Oliviero di Fabritiis is sensitive and, in general, quite slow. Apart from some hiss, the engineering remains impressive.

The three most prominent Spanish sopranos of the past 50 years have been Victoria de los Angeles, Montserrat Caballé, and Pilar Lorengar. Lorengar is the one it has been most difficult to put a finger on. First of all, she doesn't sound Spanish. Secondly, she made a particularly important contribution to the German and Austrian repertoires. Her debut at Glyndebourne (in 1956) was in the role of Pamina, and she quickly gained a reputation as a Mozart specialist. (Hear her silvery performance of "Dove sono" on the present CD and understand why.) In 1958, she joined the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. To be fair, Lorengar also sang many of Puccini's heroines (in Italian, and also in German!), and she made a fine recording of La traviata with fellow Spaniard Giacomo Aragall and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Nevertheless, I don't think it is random that the first "Classic Legends" disc to be devoted to Lorengar is titled "Prima Donna in Vienna." It was recorded in 1971.

Although everything here is either German or Austrian, it is amazing how much territory is traversed in this recital. From the formality of Mozart's Countess Almaviva to the mysterious sensuality of Korngold's Marietta is a long ways indeed. Even the selections from operettas sound authentic. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf could have matched Lorengar's achievement here, but Schwarzkopf did not have Lorengar's ace in the hole, and that is her Latin warmth. It doesn't overpower the repertoire; it merely gives it a special "burn."

This is radiant singing for which no excuses need to be made. Lorengar scores a bull's-eye in all 11 tracks. The only fault is that her interpretations are not as insightful as Schwarzkopf's – the characters are not defined and distinguished as finely as they might have been. That's quibbling, though, because the singing on this CD will send you to heaven for 52 minutes. When Arleen Auger joins Lorengar in the duet from Arabella, you'll wonder when was the last time you heard anything so beautiful. Weller is a thoughtful conductor; no routine time-beating here. As far as the sound goes, one can hear rumbling (tape noise?) at the start of some tracks, but it's easily covered by the music.

Both Renata Tebaldi and Felicia Weathers open their discs with "Tu che le vanità" from Don Carlos, and it is interesting to compare the two. Tebaldi, cooler and more worn, is every inch a queen, royally commanding attention even in her private musings. Weathers sounds warmer and more womanly – someone with whom the average person could identify – and she is in perfect command of her voice, which never lets her down. Fortunately, one doesn't have to choose between these two sopranos; one can purchase both of these CDs.

And one should. Like Lorengar, Weathers spent a significant portion of her career singing in Germany. (The Weathers LPs in my collection, including one of her singing hits from Broadway (!), all are of German origin.) I understand that her voice was quite small, and she might not have been heard to her best advantages in larger houses such as the Metropolitan. No one says that a great singer must have a big voice, however, and what Weathers does on this release, originally recorded in 1966, is first-class. One wonders, though, what she did in the later decades, because what I've been able to follow of her trail grows cold in the early 1970s. Born in 1937, she could still be singing recitals even today, so what became of her?

A slim, attractive African-American woman born in St. Louis, Weathers is the daughter of a judge, and initially pursued a medical career. (Lucky for us that she didn't!) Her voice is not unlike Barbara Hendricks's (but darker), or the young Jessye Norman's – smoky and almost husky in the lower registers, and increasingly burnished as it ascends to the highest notes, which are secure and penetrating. She seems suited to gentle heroines such as Suor Angelica, Lauretta, and so on. Her Desdemona is meek and sounds ready to accept whatever Othello has in store for her. (Apparently she sang Richard Strauss's Salome, though – something I would have liked to hear!) She does nothing particularly special with the texts nor with the characterizations, but her voice is glorious and she uses it intelligently, and most of the time that's enough. We need more voices like this today. Quadri's direction can be on the slack side, and the Vienna Opera Orchestra makes a few raw sounds. Again, the digital remastering makes the years melt away.

Copyright © 2006, Raymond Tuttle