The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

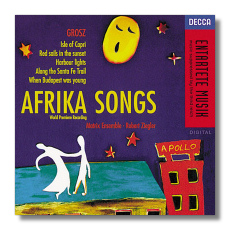

Wilhelm Grosz

Songs

- Afrika-Songs, Op. 29 1

- Rondels, Op. 11 2

- Bänkel und Balladen, Op. 31 3

- Songs (arr. by Ziegler), including "Harbor Lights," "Along the Santa Fe Trail," "Isle of Capri," and "Red Sails in the Sunset" 4

1,2 Clarey, 4 Hunter, 1 Gardner, 3 Shore (vocalists)

Matrix Ensemble/Robert Ziegler

London 455116-2 73:06

Summary for the Busy Executive: "Cross the Harlem roofs. The moon's shining. / And the night sky is so blue."

About the only major label I regularly buy these days is Decca/London, and almost solely for its "Entartete Musik" (decadent music) series, devoted to composers killed or suppressed by the Third Reich. Along with the relatively well-known names like Schoenberg, Hindemith, Weill, and Korngold, the series has also presented such neglected figures as Schrecker, Zemlinsky, Eisler, Krenek, Braunfels, Schulhoff, and Goldschmidt. As with any collection, I liked some CDs better than others. This one has become a favorite.

Grosz (I have no idea whether he's related to the artist Georg Grosz) studied with Schrecker, among others. I find Schrecker's music pretty but uninteresting – a lesser Korngold, who works the same idiom. However, he must have been a crackerjack teacher, emphasizing technical mastery (particularly of counterpoint and of orchestration), but without imposing his own late Romantic style. His students sound mainly modern and tend not to sound like each other. Grosz, based in Vienna, had several successes, including operas, chamber music, and even a symphony. He fled Vienna for London in 1934, after his works were banned in Germany. There he began a career as a pop song writer and composed a number of hits. An interesting aside: Grosz wrote many of his songs under pseudonyms (André Milos, Hugh Williams, Will Grosz, among others), so that they could be played in Germany; they were hits there as well. He moved to Hollywood to write songs for the movies and died of a heart attack in 1939, still in his early forties.

Grosz seems to have not one style, but several. However, his solid training and his lyrical imagination strike me first, whatever the style. Within his limits, he's a fantastic songwriter, as good as Weill or Korngold. I'd love to hear a purely instrumental work.

Afrika-Songs reflects the surprising influence of the Harlem Renaissance throughout Europe, as represented by the Austro-German anthology Afrika singt ("Africa sings"), apparently the first attempt to translate the poems of African-Americans into German. The translators, Anna Siemen and Josef Luitpold, don't hew all that closely to original. Essentially, they take the conventions of the blues and substitute the cliches of the Romantic German lyric, as in the following, where Langston Hughes's

I'm moanin', moanin'

nobody cares just why.

No, Lord!

Moanin', moanin',

feels like I could die.

O, Lord!

becomes

Ich leb', ich leid' alleine.

Wer fragt, warum ich weine?

Niemand, Herr!

Ich weine, weine, wein',

ich möcht' gestorben sein,

o Herr!

It reminds me of Ernie Kovacs's skit of The Lone Ranger in German – guys wearing Tyrolean hats and six-guns over Lederhosen, with the mysterious masked man in dark sunglasses ("eine silberne Kugel!"). Apparently, even something so tame in German was enough to shake up the German poetry of the time and to get other artists to pay attention. Grosz was only one of several composers to set parts of this collection. Zemlinsky used some of the poems for his Symphonische Gesänge. To my mind, Grosz beats him out, but then again I'm not Zemlinsky's biggest fan. Essentially, Zemlinsky sets the texts as he'd set anything else of similar emotional import. There's nothing really special about it. On the other hand, Grosz creates something new, out of late Mahler, Strauss, cabaret dance-band music, a little bit of the Weimar Kurt Weill, and even Jerome Kern. While African-Americans tend to bleach out in the German texts, becoming figures on the German Romantic landscape, Grosz's music returns to them some of their particularity. Grosz follows almost every song with a snappy, purely instrumental number for cabaret forces, based on the previous song. Since almost all the songs tear your heart out, the poetic conceit seems to be that even the happiest jazz has sorrow at its base. Not necessarily true, it nevertheless does give the listener something more to chew on. The songs, like the poems, deliver a range of emotion: tragedy, irony, elation, sensuousness, resignation. The "happiest," most up-tempo song, "Arabeske," in a roundabout way describes a lynching, with the same hideous irony of Frank Horne's poem. Hughes's "Night Song in Harlem" gets a transcendent, passionate treatment, where you seem to be flying over the roofs of Harlem. But each song in the set grabs you, one way or the other. For me, it stands as one of the most masterful song-cycles of its century.

The earlier Rondels show Grosz as he might have developed without the influence of jazz and pop – pure post-Romanticism. Here we most easily see Schrecker's pupil. Even so, Grosz has something of his own to say, although he says it as much through gorgeous orchestration as through distinctive melody, much like Korngold's Einfache Lieder. The Bänkel und Balladen ("Pop Songs and Ballads") belong to the tradition of social criticism of Austro-German cabaret at its best. The musical idiom resembles the music-hall traditions of England and France, with a strong dose of cultural satire in the texts of Joachim Ringelnatz and Carola Sokol. The genre reached its height in pieces like Weill's "Bilbao-Song" and "Matrosen-Song" and Eisler's "Und was bekam des Soldaten Weib" and "Ballade vom Weib und dem Soldaten."

I have more problems with the English pop songs. Grosz, like Weill, had to adapt to the commercial environment of Britain and the U.S. Unless one has a serious patron, a classical composer usually starves in both countries if he depends solely on his compositions. I'm glad Grosz made a living, but the songs themselves are rather tepid, even though almost all the ones here are still occasionally played. Patti Page had a hit with "Harbor Lights," and that should tell you everything you need to know about the song. "Along the Santa Fe Trail" is probably the best of them. It actually manages to swing a little.

The singers are almost all good. Jake Gardner, the baritone in the Afrika-Songs, is easily the best, although the mezzo, Cynthia Clarey, isn't bad. Andrew Shore has a nice sense of Viennese style in the Bänkel. The real disappointment, however, is Kelly Hunter, who does all the pop stuff. She sings consistently flat, with an annoying straight tone, besides. She sounds as if she will never have the breath to get to the end of a phrase. It's basically an amateur job. On the other hand, Ziegler and the Matrix Ensemble tackle the music with elan. Ziegler also contributes respectable dance-band arrangements of the pop stuff, and he and the Ensemble manage to get through them with a real pop feeling. If they had turned up on a Sinatra recording, I wouldn't have been surprised.

The sound is fine.

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz