The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bernstein Reviews

Bolcom Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Piano & Orchestra

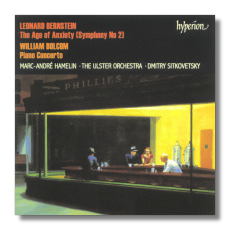

- Leonard Bernstein: Symphony #2, "The Age of Anxiety" (1948)

- William Bolcom: Concerto for Piano and Large Orchestra (1978)

Marc-André Hamelin, piano

The Ulster Orchestra/Dmitry Sitkovetsky

Hyperion CDA67170 59:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: American anxiety.

Outside of partisans, I've never understood the unwillingness to accept Leonard Bernstein's concert music. Its sheer brilliance is more than enough for me to raise him into the first tier of postwar cocmposers, and I love almost all of it. Even so, I admit the truth of some of the complaints from those on the other side. Pretentious, "meaningful" texts exercised a strong attraction on him. I would contend, however, that it rarely infected the music. Even something as blushworthy as the composer's text for the "Kaddish" Symphony stands apart from the music itself, among the finest written by an American and by a hell of a lot of Europeans, for that matter.

All three of Bernstein's symphonies fall, to some extent, into the category of "problem symphony." The second, subtitled "The Age of Anxiety" (after the Auden poem), has such an extensive part for solo piano that one could consider it a concerto equally as well as a symphony. Furthermore, it exhibits a structure unusual for either symphony or concerto. It does follow the movement of Auden's poem, but at a rather abstract remove, and you don't need to know the poem in order to follow the music, although you may better appreciate little "touches" here and there. The first movement begins with an introduction mainly for two clarinets, followed by something like two variation sets of seven variations each. The first reminds me a bit of terza rima, where elements of previous sections become the basis of the next section. The second is kind of a passacaglia. At least, it begins as a passacaglia. The ground bass then becomes the basis of the following variations. Bernstein's formal contrapuntal skill and his rhythmic exuberance both come to the fore with jazzy 7/8 passages and at least one fugato. Indeed, the first movement eschews sonata form altogether in favor of a kind of continual development.

The second movement falls into three large parts: a slow movement ("Dirge"), a scherzo ("Masque"), and a final chorale ("Epilogue"). The scherzo, chock full of Bernsteinian pizzazz and brilliantly scored for piano, harp, and the percussion section, has an immediate appeal, with its sardonic, jazzy appropriation of "Rock-a-bye Baby." Hindemith tinges "Dirge," while Copland provides the model for the "Epilogue." Nevertheless, Bernstein manages to transform these borrowings through some unknown alchemy into something uniquely his own. The "Epilogue" recycles earlier themes in a kind of phantasmagoria, as if one ascends from the subconscious to return to the everyday world. The opening clarinet duo comes back, this time scored for full strings, and provides the basis of the ending. Whatever motific variation Bernstein works takes a back seat to his considerable command over symphonic rhetoric. In a way, the score moves a lot like a ballet, with symphonic overtones. Bernstein primarily creates drama.

On the other hand, William Bolcom's piano concerto mainly comments on other music. The air of prodigy has long clung to Bolcom, a student of Milhaud, although by now Bolcom is at least seventy. I've always found him inconsistent. Certain pieces I love. Others pass by without sticking. The piano concerto's first movement takes an ironic look at Gershwin's Concerto in F. Gestures and phrases from the earlier concerto show up in this one, all of a sudden postmodernly cool. The concerto was a U.S. Bicentennial commission, and in 1976, on the heels of Viet Nam and Watergate, Bolcom wondered what there was to celebrate. It's a fair question, but the art has to measure up. Here, Bolcom's mixture of vernacular and super-slick postmodern collage only half works. The really vital parts of the movement are the vernacular ones. The trendy collages come off, not ironically but snarky. Bolcom's concerto differs from Gershwin's in the same way wit differs from imagination, to borrow Coleridge's distinction. Blood flows through the veins of Gershwin's concerto, Evian through Bolcom's.

Things pick up in the second movement, titled "Regrets." Bolcom has said that he intended an ironic comment on the Gershwin second movement, but you'd never know it. In the liner notes, Peter Dickinson writes that it's difficult for a listener to pick up musical irony. I would add "unless it's extremely broad." Certainly if Bolcom had said nothing, I wouldn't have known. I would concede that both Gershwin's and Bolcom's share a kind of nocturnal reflection. However, Bolcom to me has bigger fish to fry than mere commentary. For me, if I had to assign an extra-musical meaning, it meditates on lives wasted in the war. Musically, a nearly atonal, though quiet, duet for two clarinets, dissonantly developed in "conversations" between small orchestral groups and the solo piano, morphs at its climax into a bittersweet "pop" version for full orchestra. Then it quiets down, to where it leads directly into the finale.

The last movement is an Ivesian patriotic smorgasbord. But where Ives is proud of the country's "barbaric yawp," Bolcom gets mad at its vulgarity. "Taps," for example, begins as a heartfelt song, becomes inflated, and ends in sniggers, as if to say that once-genuine patriotism has been cheapened. My politics have little to do with my discomfort and dismay at this. In fact, I happen to agree with Bolcom up to a point. But as cynical as I am, I want to believe in a pure core of belief, away from opportunistic officials. There's little point in at least paying taxes otherwise. Bolcom's "over-the-top" vulgarity has little humor or humanity in it. I would rather listen to Sousa marches, quite frankly.

Sitkovetsky and his Ulstermen simply don't get it. They play too stiffly in the Bernstein. They don't know from swing, although they seem to get the notes. The playing improves in the Bolcom, mainly because Bolcom's idiom lies closer to contemporary European trends. Still, there's not a lot of poetry here, and Bolcom's concerto needs it badly. No complaints from me about Marc-André Hamelin. He gives these readings whatever life they achieve.

Copyright © 2009, Steve Schwartz