The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bantock Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

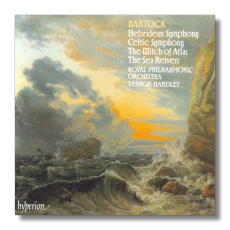

Granville Bantock

Symphonies and Tone Poems

- Celtic Symphony

- The Witch of Atlas

- The Sea Reivers

- A Hebridean Symphony

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Vernon Handley

Hyperion CDA66450 73:30

Summary for the Busy Executive: Musical malteds.

Bantock flourished in the early years of the twentieth century until the First World War. Many people admired and loved both his music and his character, exceptionally generous, especially to young composers, whom he helped financially and by conducting performances of their works. He belonged to a wing of British music that included Delius, Brian, Holbrooke, and Boughton. His music is very much of its time, and I should say it has, in its extra-musical concerns of orientalia, hothouse sex, and Celtic twilight, links to the literary Decadents of the Victorian Eighties and Nineties. By the Twenties, however, his music had ceased to matter, in a way that Delius's and Brian's, at any rate, had not, and he still had forty years to go.

Bantock characteristically conceives of his music on a grand scale, and he writes gorgeously for the orchestra. For sheer sonic beauty, nobody beats him, not even Ravel. As far as I'm concerned, his orchestra sings more radiantly than Richard Strauss's, the composer to whom most compare him. I find the idioms and the sensibility, however, very different. Strauss's music reminds me of a Gustav Klimt canvas, while Bantock's reminds me of a kitschier Thomas Kincaid, with gilt highlights liberally applied. Moreover, Bantock lacks the ability to invent memorable themes and to tell a tight story. The things he calls symphonies meander like bad film scores. They lack the architectural spine of Mahler or Sibelius or even Richard Strauss. I trace some of Bantock's success with his original audience to extra-musical considerations – part of the general protest against Victorian cultural strictures that led ultimately to Modernism. However, as a poet like Auden finished off Ernest Dowson and Lionel Johnson, so Vaughan Williams, Walton, and Britten sank Bantock, Holbrooke, and Boughton. While the first three transcend their time, the latter trio is very much of their time. For me, their music is, at its worst, an exercise in nostalgia; at their best, a deeper insight into a specific historic milieu.

Of the Bantock orchestral discs Hyperion has so far released, I like this one the best. As with all of Bantock's music, these works present one gorgeous moment after another. My favorite is the opening to the Celtic Symphony, with a I-iii modulation, common in Celtic music but relatively rare in the concert hall. One usually encounters at least triple wind and brass in Bantock scores, so the instrumentation for strings (divided into a rich seven) and six – count 'em, six – harps is comparatively chaste. Throughout the piece I kept wondering whether he really needed all six harps, and it turned out that he does for one great moment toward the end. The mass of harps stands up to the mass of strings at the final climax. On the other hand, structurally, one damned thing follows another.

The tone poem The Witch of Atlas has sturdier architecture – a house of sticks rather than a house of straw – but lacks the Celtic's melodic charm. Even so, it has trouble holding together, despite its use of "character-tags" for various aspects of Shelley's poem. Things wind down and start up again, usually a sign of a weak hand on the tiller. Bantock seems to be an artist fixated on physical beauty, and the snippets of Shelley's poem he chooses to depict are basically painterly, rather than "story." The trap of this is that the music doesn't move with purpose. But, boy! it sounds so good!

The Sea Reivers, at slightly under four minutes, is one of Bantock's shortest and tightest. According to Grove, he originally intended it as the scherzo of the Hebridean Symphony. I prefer it to the scherzo he actually wrote. Unlike the other works on the disc, it jumps, it moves from here to there. It's a grand symphonic paragraph of High Romanticism and shows that Bantock could write symphonically when he put his mind to it. It premièred in 1920 to immediate acclaim. Again, other music crowded it out, to the point where this recording amounts to a revival.

The Hebridean Symphony (1916) had such critical success in its time that the Carnegie Trust published it in full score as an artistic service to the nation. It collects many great sounds. It builds without ever really coming to a boil – what Tovey used to call "a Prélude to a Prélude to a Prélude." Again, it reminds me of a film score. If I were listening while watching, say, Captain Blood, it would catch me up.

Handley and the Royal Phil do a bang-on job. The sound, the most important component of a Bantock score, glitters and roars. It's as if one has sprinkled Disneydust in the delicate passages and had shipped out to sea in the loud ones. One doesn't need to hear Brahms all the time. If you need a good sonic wallow, Bantock's the guy.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz