The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Billings Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

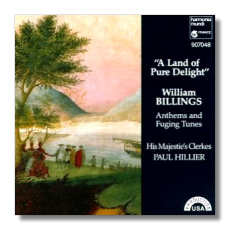

William Billings

A Land of Pure Delight

Anthems and Fuging Tunes

- O Praise The Lord Of Heaven

- Is Any Afflicted

- Emmaus

- Africa

- Funeral Anthem: Samuel The Priest

- Shiloh

- Jordan

- I Am The Rose Of Sharon

- Euroclydon

- Hear My Pray'r

- Rutland

- David's Lamentation

- As The Hart Panteth

- Creation

- Brookfield

- Easter Anthem: The Lord Is Ris'n Indeed

His Majestie's Clerkes/Paul Hillier

Harmonia Mundi HMU907048

Reissued as Harmonia Mundi HCX3957048:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

William Billings, one of the first true American composers (1746-1800), was a tanner and a "singing master" – that is, a person who taught choirs and small vocal ensembles to read music and to sing in parts. His tune "Chester" was the Revolutionary War's equivalent of "Over There." The "singing schools," perhaps the greatest force in the musical life of the colonies and the early republic, split into two branches, reflecting a cultural split in the country itself: New England vs. the South. The music is vocal, mostly choral, and intended mainly for use in churches. Most of the composers in both schools did other things to make a living. Justin Morgan, a highly original composer of the Southern school, among other things raised and bred horses. Very few composers had more than rudimentary training. As a result, the music sounds like a stitching-together of half-remembered Baroque counterpoint, Renaissance modes, and Bay Psalm hymnody – handmade, the opposite of slick. This resulted in a vigorous music, at its best, which differed from the current European product. The lack of sophisticated technique greatly emphasized the importance of quality material – melody, declamation, harmony. It succeeded so well that it soaked into the musical life of the country, through the Sacred Harp collection and the Big Sings of Kentucky, with hardy persistence up to the end of the 19th century, when it began to decline. Still, it flourished in isolated rural areas until after World War II.

In the 30s, modern American composers, looking for an indigenous musical tradition, helped revive the music by basing compositions on either the older procedures (Henry Cowell's series of Hymns and Fuguing Tunes) or the tunes themselves (Schuman's New England Triptych, Copland's Appalachian Spring). Robert Shaw very early blazed a trail in reviving the music for performance, as far back as the days of his Collegiate Chorale. To me, however, Gregg Smith started the boomlet in earnest, in a landmark Columbia album devoted exclusively to selections from Billings's "Continental Harmony." The Western Wind vocal ensemble also produced at least two albums devoted to Billings and others, including those composers of the Southern school.

The forms are fairly simple: mainly, hymns, anthems, and fuguing tunes. A hymn consists of a tune harmonized chorale-fashion, in block chords. Neither Bach nor Handel would recognize a fuguing tune as a fugue. It is indeed imitative counterpoint, often a simple round like "Row, Row, Row Your Boat," but never anything as complicated as a "school fugue." Anthems are elaborate works in several sections and make use of both hymn and fuguing technique, often with passages sung by a single voice.

Concert performance of this music has undergone several changes. Neither Shaw, Smith, nor Western Wind sang the music any differently than other repertoire. However, the revived Sacred Harp and Historically Informed Performance movements have affected the approach. Andrew Parrott and the Taverner Consort aim for an idealized Sacred Harp sound, complete with twang, but with sharp rhythm and dead-on intonation. Hillier and the Chicago-based His Majestie's Clerkes aim for a middle ground: a "normal" concert sound modified by slight vowel changes shaded toward dialect and less subtle dynamic shifts. The album mixes old favorites with, as far as I can tell, première recordings, so repertoire should appeal to old hands as well as to newcomers.

The album succeeds very well most of the time. Quiet numbers like "Emmaus" (an alternate setting of the text "When Jesus wept"), "Samuel the priest," and the gorgeous "Rutland" come off best. Perhaps not purely coincidentally, the choir in these numbers stops playing at rusticity and achieves a smooth, conventional blend. To be fair, however, Hillier's ideas come off best (and very effectively indeed) in "David's Lamentation." Still, Hillier walks a fine line and sometimes fails. The choir very often forces the tone (particularly the males) and, in the last selection especially ("The Lord is risen indeed"), both attacks and pitch spread. The approach works best in short, snappy numbers like the familiar "I am the Rose of Sharon." Yet even here, His Majestie's Clerkes (who is the Majestie near Chicago, now that old man Daly is dead?) fail to generate the rhythmic electricity of either the Gregg Smith Singers or Western Wind account. The nine-minute "As the Hart panteth" becomes dull, despite beautiful rendering of individual sections, due to the conductor's failure to shape the climaxes of the piece and to keep a forward sense of motion.

If you don't know the music, this might be a good place to start. For more on early American music, however, check out Gregg Smith's "America Sings, Volume 1: The Founding Years," a Vox Box two-fer of nearly 147 minutes (CDX5080). It isn't all Billings, but you do get some selections by Morgan and an entire group of music by the American Moravians (very Handelian and as good as some Handel). One solution is to get both Hillier and Smith.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz