The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Walter Piston Reviews

Quincy Porter Reviews

Morton Gould Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

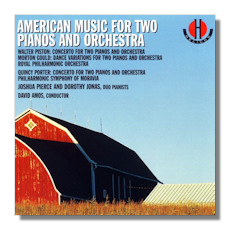

American Music for Two Pianos & Orchestra

- Walter Piston: Concerto for 2 Pianos & Orchestra

- Quincy Porter: Concerto for 2 Pianos & Orchestra *

- Morton Gould: Dance Variations for 2 Pianos & Orchestra

Joshua Pierce & Dorothy Jonas, pianos

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/David Amos

* Philharmonic Orchestra of Moravia/David Amos

Helicon HE1044 57:55

Summary for the Busy Executive: Wonderful.

The two-piano concerto is a fairly rare beast, despite acknowledged masterpieces by Bach (harpsichords, of course), Mozart, and Poulenc. If you think about it, the genre invites a composer to step up his contrapuntal game. After all, a piano reduction of a piano concerto requires two pianos, one representing the orchestra. Consequently, a reduction of a two-piano concerto requires three – and all that many more voices. Of course, you can (and most composers do) simply double parts and trade in a greater volume of sound, but this gets tired over the long haul. You want things like antiphony and melodic intermingling to build interest. Nevertheless, this hurdle hasn't deterred composers, often spurred by commissions by well-known two-piano teams like Vronsky and Babin, Whittimore and Lowe, Sellick and Smith, Robert and Gaby Casadesus, and so on. However, we still don't often hear these works in concert, I suspect due not to quality, but to the facts of economics and box office.

One of his finest scores, Walter Piston's concerto comes from the late part of his career (1959), when his star as one of America's best symphonists had dimmed in the glare of new suns. A jewel of the Harvard faculty and the teacher of a host of A-list composers himself, Piston became respected but old-hat in serious circles while the then-avant-garde – Carter (a Piston pupil), Berio, Stockhausen, Cage, Boulez, and Babbitt, for example – took center stage. The same thing happened to just about every other American composer of Piston's generation and neoclassic style. Many really good scores fell into oblivion, if anybody performed them at all. At any rate, Piston's concerto premièred in New Hampshire, of all places, and deserves a wider hearing. It has the young energy of Piston's music in the Thirties and Forties, especially of the Violin Concerto #1 and of the Symphony #2. The first movement, a sonata, plays with two main ideas: the first, an athletic one based on fourths and fifths; the second, quicker and more chromatic. Piston fully uses his resources in an ensemble strategy that recalls the concerto grosso. The orchestra (ripieno) and the soloists (concertato) reinforce, call and respond, sing alone, and intermingle. The solemn slow movement begins with the two soloists gracefully handing a long-breathed melody off to one another. The orchestra briefly takes over, and the soloists continue with an insistent rhythmic idea which continues alongside the expansive theme. The rest of the movement works out the juxtaposition of these two gestures. The finale rounds the concerto off with an opening theme evoking boulevardier insouciance.

Quincy Porter's name has all but disappeared, except among chamber musicians. He studied with both Horatio Parker at Yale and with Ernest Bloch. The latter influenced him more by far, although Porter never imitated. Porter wound up as Piston's counterpart at Yale. Written in 1953 to a Louisville Orchestra commission, his Concerto for Two Pianos won the Pulitzer Prize. In one continuous movement, it's the most concentrated work here, though not as much fun as the Piston or the Gould. It sings soberly and somberly, but it does sing. The score falls into three sections: a slow introduction; a jumpy, propulsive allegro, which takes up most of the piece; putting on the brakes, to return to the slow section (so you shouldn't forget it) for a brief coda, which ends with a final punch of the allegro. Porter doesn't work with full-blown themes, but with smaller bits (most heard in the first section), which he combines and recombines. What seem like unconscious echoes of Rite of Spring occasionally bubble up to the surface, with much different effect than in their original context. The two-piano writing is immaculate, probably the best-suited of all the works here to the combination.

Written for Whittimore and Lowe, Morton Gould's Dance Variations also comes from 1953. Gould's humor and quick-wittedness step to the fore, but one shouldn't mistake this as a slight work simply because it doesn't pull a long face and tries to please. One discovers here much original thinking and what seem "basic finds" – like Liszt's diminished chord, Vaughan Williams's use of the flatted seventh and the pentatonic scale, or Stravinsky's freeing of rhythm. Here, much of the musical play derives from the title. For example, the first movement is a jazzy chaconne with a six-note bass – that is, a dance in triple time, probably originating in Spain, on a repeating bass with variations above that foundation. The second movement reverses the emphasis: here, Gould takes a theme and rhythmically varies it through a mini-suite of dance forms – gavotte, pavane, polka, quadrille, minuet, waltz, and can-can. The third movement, entitled "Pas de deux (Tango)," is a slow, sultry tango that often moves in five-beat phrases, rather than the usual four, while the finale, a tarantella, like the mythical red shoes, aims to dance the metaphorical feet off the listener. Gould plays all sorts of games with a "Dies irae" bit written like a playground chant, canon, stretto, the theme sounding against itself played half and then a third as fast. The orchestra blazes in a Stravinskian Pétrouchka way, but with an agility and lightness missing from that earlier score. As Gould once joked, "That Stravinsky. He's always stealing from me." But with Gould one hears an American expansiveness, rather than the stamp of a peasant's boots.

Kudos to Pierce and Jonas for their commitment to this repertory. They play at a very high level indeed. David Amos, a severely underrated conductor, brings his usual alertness, rhythmic snap, and discipline to two different orchestras and provides sensitive accompaniment. A winner and highly recommended, especially for listeners who believe they hate Modern music.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.